Experiences of Frank Correa and Hetty Van Langenberg during World War II.

FOREWORD

It seems appropriate to mark our son Anthony's Fortieth Birthday with this document which relates to his father's experiences during the turbulent years of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in the Second World War.

We all recall Frank often reminiscing about the "war days" and it would be a pity to lose all these vivid accounts with the passage of time. We hope our grandchildren one day would be interested in reading their Grand Dad's description of what happened and be proud of the significant role their forebears played to secure a safer world.

Thanks are extended to Joyce Van Langenberg who has kindly given permission to include her account of events as told to her by her mother-in-law, Hetty, after the war.

Hetty's story corroborates what happened during the chaos after Hong Kong fell and is dedicated to Grandfather Frank Soares in gratitude.

Saudades

1st August 2008

OVERVIEW

The invasion of Hong Kong on Monday 8th December 1941 by the Japanese Imperial forces shattered the tranquillity of Hong Kong. Its population of over 1,500,000 dwindled to 600,000, the remaining residents enduring four years of extreme deprivation as the occupying forces imposed harsh conditions in order to maintain law and order.

China's defeat in the First Opium War in 1842 resulted in Hong Kong being ceded to the British in the Treaty of Nanjing. Besides paying an indemnity, five Chinese ports were opened for trade in China and Hong Kong was ceded to become a British colonial outpost, a strategic port on the south China coast at the mouth of the Pearl River.

British rule brought stability and employment opportunities; many nationalities including the Portuguese from Macau gravitated to Hong Kong and in fact Macau's economic decline can be traced to the establishment and rapid growth of the British colony. Before the Pacific war, Hong Kong in the 1930s was a relatively quiet British colony, an entrepot port; it relied chiefly on trade and commerce from China.

Hong Kong's rival at the time was freewheeling Shanghai, the premier city on the north China coast. It was a mecca for foreign capita1ists with its sophisticated international settlements and trading houses, many of them British. Foreign capitalists, warlords, and Chinese industrialists, prostitutes, gamblers, millionaires and beggars shared their turf with thugs and thieves. Dubbed the "Babylon of the East", the teeming city became a magnet for the entrepreneur and adventurer. An added attraction was the "extra territorial" status for foreigners which meant that they were not subject to Chinese law. Instead foreigners were under their own national law administered by Consuls or Chargés d'Affaires. A Chinese city but real power was held by foreigners, an obvious bone of contention for many Chinese who despised the city's western decadent influence.

Imperial Japan became westernized and industrialized in the Meiji era (1868-1912). Borrowing from western technology, introducing democratic reforms in government, financial institutions and the judiciary, and improvement in communications facilitated the establishment of a modern nation to rival the West in 80 years. It was an economic miracle that needed to fuel its industrialization with scarce raw materials. A national government came to power in the 1920s promoting Japan's expansionist military power in order to secure its prosperity. Japan's expansionism had already gained Formosa (Taiwan) and parts of resource rich Manchuria with the defeat of China in the First Sino Japanese War during 1894-1895. Conflict with the Russians (Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905) marked the first modern war where an Asian country defeated a European power, the victors claiming part of Sakhalin Island, and additional mineral rights in Manchuria. The Russian defeat allowed the Japanese to annex Korea in 1910 without opposition.

The Japanese military coveted China for centuries, its dream was to bring her under strong rule and harness its vast mineral and industrial resources thereby securing its own economic prosperity. In the 1930s, the ongoing civil war was weakening China; the Imperial Army, encouraged by a right-wing nationalist government, were confident that they could destroy the communists and also end the Nationalist's unpopular reign of terror and corruption.

Thus the scene was set with Japan again invading China in 1937 from their base in occupied Manchuria with the subsequent fall of the Nationalist capital and the terrible events of massacre of 300,000 Chinese in the ensuing Rape of Nanking. In September 1940, Imperial Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany with Asia becoming Japan's "sphere of influence". The Japanese invaded northern French Indochina on 23rd September 1941 and the subsequent oil embargo imposed by the United States gave the Japanese military an excuse to launch an attack on Pearl Harbour, oil in Borneo and Balik Papan in lndoneasia being the prime motivation.

As Hawaii was being attacked on Sunday in December 1941, the international dateline meant that Japanese troops simultaneously began to invade Kowloon on the 8th December, its residents ill-prepared for the four years of hardship that followed.

2 LIBERTY AVENUE

The Soares Family lived in a grand old mansion at 2 Liberty Avenue in Homantin. This area was developed by Francisco (Frank) Soares; the project began in 1912 to provide affordable housing for the European community in Kowloon.

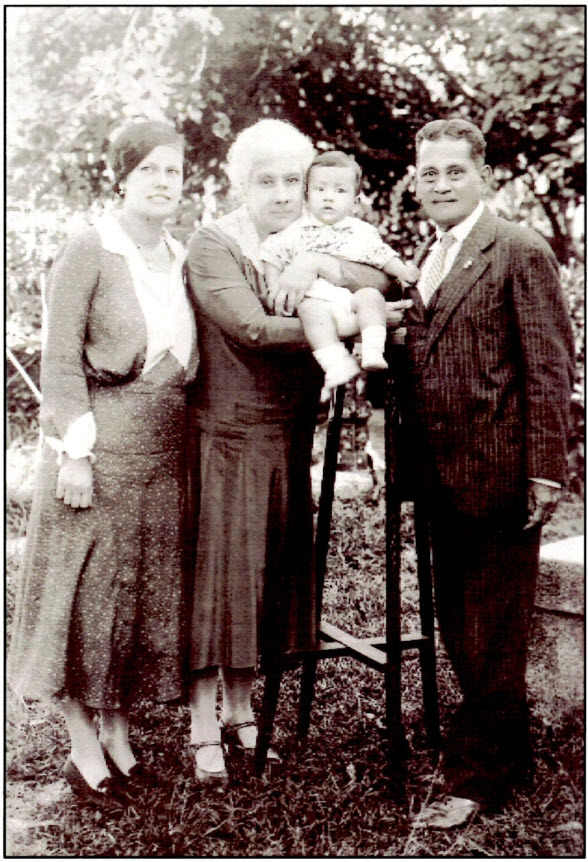

After marrying Charlie Correa who was an auditor at Jardine Engineering in China, Julia moved to Shanghai and the newly married couple set up home at Rue Paul Henri in the French Concession. Frank (1931) and Bosco (1933) were both born in Shanghai, Julia enjoying all the excitement and many attractions of a bustling city which was in its heyday.

After three years, the pull of family eventually persuaded them to return to Hong Kong. Charlie managed to secure work with an American broking house Swann, Culbertson and Fritz. Idyllic years ensued at Liberty Avenue, the grand mansion comfortably accommodating the expanded Correa clan with two noisy grandsons, doting grandparents and three bachelor uncles Joannes, Luigi and Mem.

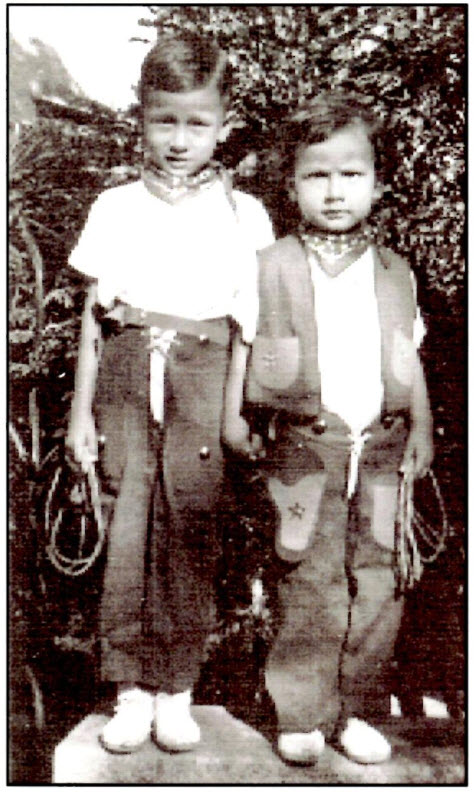

The two boys had a carefree childhood, the centre of attention in a busy household. They played in a garden resplendent with exotic flowers, a large vegetable patch and numerous fruit trees, Grandfather Soares being a keen horticulturalist. A diverse Portuguese and Eurasian community settled in the area, a park conveniently opposite their home became the meeting place for neighbourhood children who gathered daily to play endless games, skate or ride bicycles.

"Auntie Albertina's kindergarten" was conveniently situated opposite 2 Liberty Avenue so their early education was held informally in her dining room where Frank remembers there was a huge table where children sat around learning early reading and writing skills. Formal education began when Frank, and later Bosco, were enrolled at La Salle College, the only Catholic boys school in Kowloon in those early days, which was run by Christian Brothers.

Tragedy struck the family as in the period of three years, between 1937 -1940, their baby brother Gabriel, sister Pamela and Grandmother Emma passed away. The devastated family had hardly recovered from the sudden loss of three loved ones when Charlie's job at the stock broking firm was terminated, the commencement of war in Europe bringing financial instability. Fortunately he managed to secure employment with Bristol Myers in Shanghai beginning work immediately, and made plans to move his family to join him in early 1942 once he found accommodation and schooling for his young sons. His brother, Tony Correa, who worked for General Motors in Japan, was similarly transferred to the Philippines. Separated from family and friends, he endured terrible hardship and witnessed horrendous scenes of street fighting in 1945 with huge civilian casualties during the American advance to recapture the occupied city.

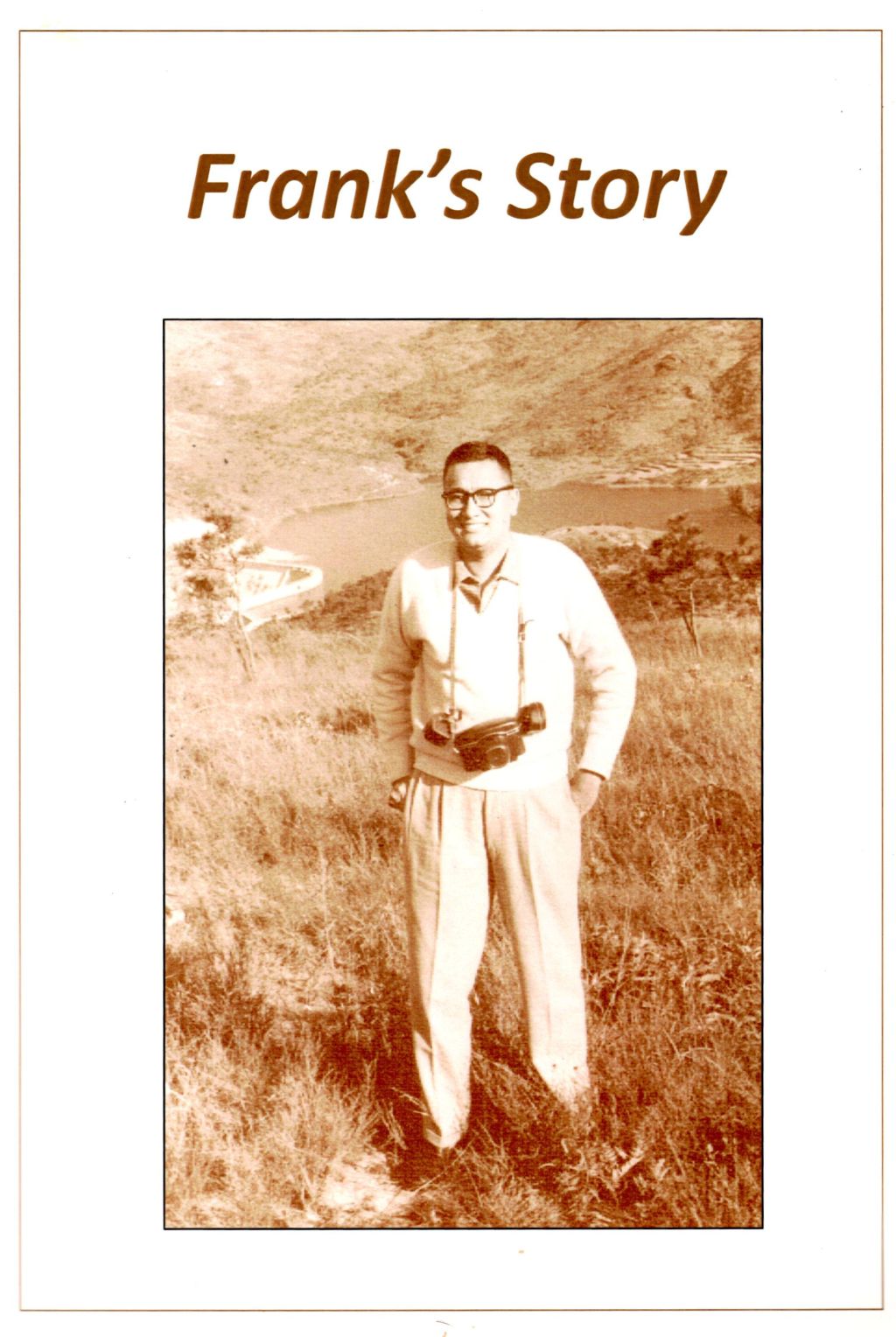

FRANK'S STORY

I was 10 years old in 1941, talk of Japanese imminent invasion ran rife and was in every conversation, occasional air raid trials added to the tension. There were rumours of fifth columnists, sightings of Japanese bomber flights over fortifications and the Japanese navy were slowly encircling the Colony, sinking junks carrying food for the Colony, they also seized a British lighthouse and occupied two islands immediately south of Hong Kong. Exacerbating the situation were thousands of refugees crossing the border from China increasing food shortages.

We learnt that with Japanese troops gathering at the border, women and children of British stock were being evacuated to Australia for safety, a bone of contention for many local British subjects. Hong Kong was inadequately defended with only two battalions of British troops, the Royal Scots and Middlesex regiments, two Indian regiments – the 5/7 Rajput and the 2/14 Punjab , a Canadian brigade which arrived in November, supplemented by a local volunteer force of 1,750 men known as the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC).

My uncles Mem (No5 MMG Portuguese Company) and Luigi (No 6 Lewis Gun AA Portuguese Company) were notified that there would be a trial mobilization on Monday 8th December, the former having only just returned from two weeks training camp in Fanling. They were told to advise their employers that the trial mobilization was for an indefinite period. Uncle Luigi left at the crack of dawn, we fortunately managed to farewell Uncle Mem not knowing that our next meeting would be behind the bars of the prisoner of war camp at Sham Shiu Po Camp.

BROTHER CORNELIUS AND DETENTION

Our Class Five teacher was Brother Cornelius who was very strict and in the habit of giving us detention for any minor infringement. Our punishment on the wintry morning of Monday 8th December 1941, was some sort of physical exercise program to toughen us up and we were told to bring along T-shirt and shorts for afterschool punishment.

It was a beautiful morning with clear skies and I left home at 8 a.m., running down Waterloo Road to catch the No 7 bus for La Salle College. About a hundred meters from home sounds of aircraft grew louder culminating with explosions in the direction of Kowloon Peak. A few minutes later, I recognized the Japanese emblem on the planes as they pulled out of their dive flying again over Homantin heading for Kai Tak Airport to launch an aerial assault on the remaining old World War 1 R.A F. planes. In a matter of minutes thick plumes of smoke rose in the air, I reeled around to dash home and warn everyone that the Japanese had attacked. Uncle Mem had not left yet and was having breakfast and I recall shouting the news, all of us shocked and fearful having heard stories of Japanese atrocities in China. Typically, Uncle Mem calmly continued to finish breakfast before going up to his room to prepare for the army transport truck to pick up his contingent at noon, mostly Portuguese living in our neighbourhood. I will never forget watching him get on board the army truck with a thumbs-up and his characteristic handsome smile.

THE BATTLE FOR HONG KONG

The Battle for Hong Kong by Oliver Lindsay (Hong Kong University Press) gives a very accurate account of what happened during those dark days. It was revealed that the British War Office knew the Colony was a vulnerable outpost with the Japanese firmly established in Mainland China. In the absence of a strong fleet in the Far East, and forces stretched to the limit with the war in Europe, Hong Kong was left to defend itself for as long as possible with its limited resources.

Lindsay also documents that suggestions were made by the military commanders to make Hong Kong an "open city" allowing Japanese occupation without resistance, thus saving thousands of lives. He explains that this option was rejected as the War Cabinet wanted Hong Kong to be defended for British prestige. The rational was that appeasement would mean political and moral weakness which would negatively influence the Chinese determination to continue their fight and discourage the neutral Americans from joining the European Allied war effort.

Military archives show that the British Battle Plan was for three battalions, the Royal Scots and the two Indian brigades, to fight on the Gin Drinkers' Line, a ten-mile frontage in the New Territories. This was difficult terrain extending from Shing Mun Reservoir in the west across Jubilee Reservoir, Needle Hill to Shatin then extending to Sai Kung. The remaining Middlesex Regiment, a machine gun battalion, was to defend the pill boxes on Hong Kong island. The newly arrived Canadian brigade was charged to defend the island from the south in case of a landing by sea. The Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps were dispatched to the island – Uncle Mem in a machine gun unit was at Mt. Davis whilst Uncle Luigi was at Aberdeen manning antiquated Lewis guns.

Kowloon fell in a matter of five days and the British withdrew to Hong Kong island on 13th December despite valiant fighting. We awoke on Christmas Day, 25th December 1941 with the news that Hong Kong island had fallen and the colony had surrendered to Japanese forces.

LOOTERS AND ANARCHY

Violence and looting began immediately with news of the British withdrawal from Kowloon and for a week anarchy reigned as looters began to enter homes brandishing knives and guns, threatening residents. In order to maximize the pillage, looters commandeered vehicles from the Kowloon Motor Bus Company stripping houses of all their contents and looking for valuables especially cash or jewellery. (See attached account by Joyce Van Langenberg who now lives in the UK.)

The looters found easy entry into homes in Kowloon Tong and Kadoorie Avenue as owners abandoned their homes seeking security on Hong Kong island which they naively thought to be impregnable. The enclave of Homantin was the next target and as my grandfather Frank Soares was the Acting Consul General for Portugal, a neutral country, many families sought refuge at his residence for protection from both the rampaging looters and the advancing Japanese forces as the conquering troops gradually penetrated into Kowloon.

REFUGEES AND PROTECTION

The Portuguese flag hung proudly at 2 Liberty Avenue; in a matter of days we had over three hundred and fifty people seeking refuge at our home. My grandfather ably formed a committee of trusted individuals to secure the house and surrounding streets, organize food supplies and obvious sanitation needs.

Families arriving at our doorstep were asked to bring along food to contribute to the emergency supply. We were fortunate that some affluent Chinese seeking temporary shelter brought a stock of rice which helped immensely to feed such a large number of people. We were terrified by the constant shelling by the British artillery which was directed at Macpherson Park where the Japanese guns were located. This was not far from our home and during the duelling sessions everyone huddled on the ground floor praying that a stray shell would not hit our house. I was told by a British officer after the war that that they knew where the Japanese guns were located but did not have air power to accurately determine their position. The Japanese guns were concentrating their fire on Mt Davis where, amongst other units, the No 5 MMG (Portuguese) Company was dug in and this included Uncle Mem who retold countless stories of his experience when released from POW camp.

I recall being outside when an unexpected British shell exploded on a vacant lot where Wah Yan College now stands and a piece of shrapnel landed close to my feet. Stupidly grabbing it with the intention of running home to show off a souvenir, it singed my hand badly causing an immediate blister – mother's admonition could have been heard all the way to Lion Rock!

Together with the neighbouring homes it was decided to form vigilante groups and patrols were maintained around the clock which included surrounding streets. These groups were manned by the remaining elderly men, some who fortunately held shooters' licenses, and we therefore had a useful supply of guns in our possession. I recall that all the children had to line the staircase of our home and pass bricks up to the roof. We stripped our garden of all bricks and stones with the plan to use them as projectiles should the looters attempt to storm the house. A few skirmishes occurred in the neighbouring streets but the looters soon realized that we had guns and numbers and we were left alone to wait for the victorious Japanese troops to arrive.

Sanitation was a major hygiene problem; houses in those days were not connected by pipes to a sewerage system and "night soil" was collected regularly along lanes that ran between backyards. In order to solve the problem, huge holes were dug in our rear garden to dispose of the accumulated "night soil" of so many unexpected refugees. One of these holes was dug near a mango tree which for years had never born any fruit. In the summer of 1942 it exploded with blossoms and later huge fruit which was a source of food for our then starving household. We concluded that the "night soil" we buried near the tree contributed to this unexpected magnificent harvest of golden mangoes. (This method of fertilization in agricultural has long being utilized in China.) Mangos have been my favourite fruit from that time onwards.

I remember my uncle's car cleaner asked my grandfather for shelter and he brought his family along, squatted in our garden, erecting a makeshift shelter under a tree. Every day he would disappear for a few hours to return in the evening with a full bag. One of the refugees living at our home, an observant woman, became suspicious and demanded the car cleaner open his duffle bag. He revealed items taken from residents from Kowloon Tong who were sheltering at our home! Anger erupted; one of the elderly men wanted to lynch the robber and was stopped by saner people who decided to hand him over to the Japanese authorities the next day. He was then locked up in a shed in our backyard; however by some luck he managed to escape and climbed up a nearby drainage pipe escaping with his life. His family likewise disappeared without a trace.

In January 1942, many large items of furniture were displayed at the "looters market" in Yaumatei and Mongkok and people identified their own silverware, dining sets, furniture and even their pianos, all for sale and ironically they could re-purchase their own belongings if only they had the money. During the occupation I recall seeing trucks on Gascoigne Road headed for King's Park with prisoners, where we learnt many were summarily executed; law and order quickly returned with such harsh occupying forces.

SURVIVAL

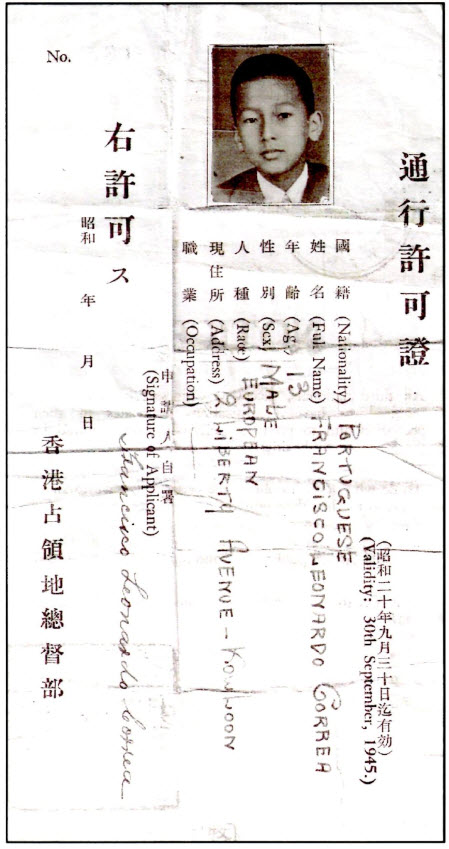

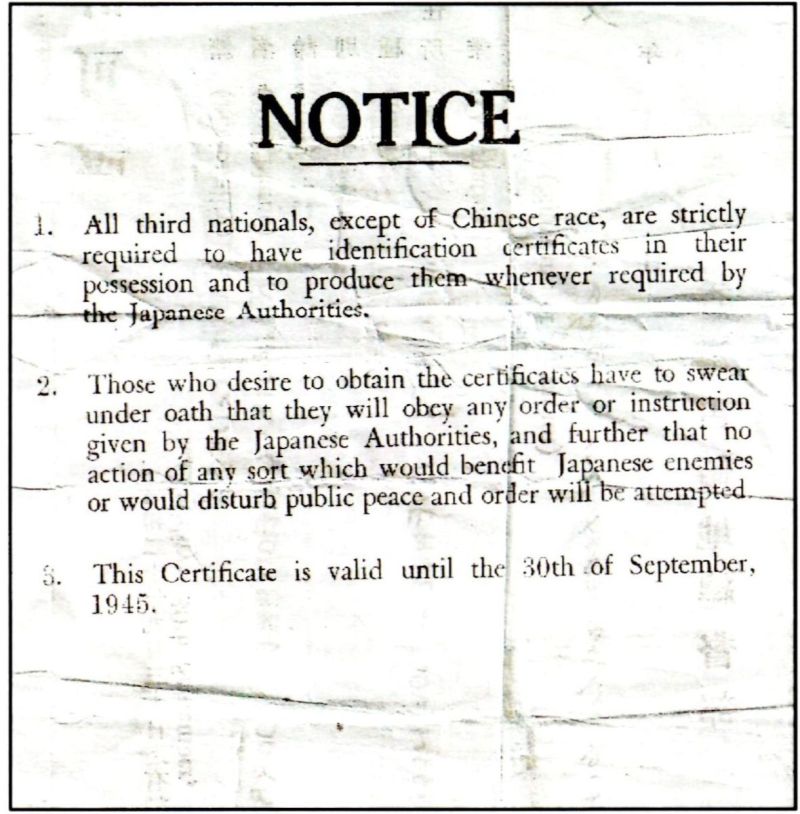

Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day 1941; it took a few days for the Japanese military to take full control of the Colony, swiftly enforcing a curfew and shooting looters or anyone suspicious on the streets. Portuguese neutrality was respected and, as conditions stabilized, families gradually returned to their own houses, fearful of how to survive the Japanese occupation and often finding their place stripped bare of all their belongings.

Hong Kong was regarded as a military port primarily to support and service Japan's war effort in the South Pacific and Indian sub-continent. The population was deliberately reduced and in order to achieve this the authorities stopped all trading and manufacturing, closed educational facilities and withheld food from the civilian population. The Chinese were expected to return to China to their villages and "third nationals" were encouraged to depart for Macau.

My Grandfather decided to remain in Hong Kong due to his position as Portuguese Consul but encouraged his community to leave for the safety of Macau, issuing papers to facilitate this exodus. Uncle Joannes decided to leave for Macau. However, my mother resolved to stay, supporting her father who was by then a widow; the ensuing years became a daily a battle for survival. My mother was a robust woman and withered down to 90 lbs as she tried to find adequate food for her aging father and two young sons. She also took up smoking to overcome the stench of dead bodies in the streets. We saw our family cook die of starvation on Argyle Street.

Our one remaining amah, a talented seamstress, suffered from tuberculosis and I had to take her to Kwong Wah Hospital as her condition deteriorated rapidly. It was some distance from Homantin; supporting her arm, we slowly walked along looted streets, terrified of being stopped as thugs ruled the areas outside of our safe perimeter. It was difficult to leave her alone as she knew the seriousness of her illness and that she would not survive. Holding my hand, she did not want me to leave and together we cried, this war already claiming so many lives.

The Japanese occupation robbed me of my childhood as my mother increasingly relied on my help in the absence of my father. Our education came to a standstill and La Salle College was converted to a Japanese military hospital. The religious brothers departed for French Indo-China.

FOOD GLORIOUS FOOD

Food become our prime concern as supplies and our money dwindled. The Macau Government was allowed to send shipments of rice to the small Portuguese community that remained; however, these were irregular and dependent on the whim of the Japanese authorities.

Our neighbour, the Houghtons, had some chickens and I persuaded my mother to purchase some chicks as they would become a much needed food source producing eggs. She had to be assured that the enterprise would be self-sufficient as we were counting our pennies and the chicks needed to be fed. Fortunately the fowl had the run of our large garden and I learnt that they could be fed the dregs of soybean protein which could be bought cheaply from the market.

My poultry grew from twelve to thirty by the time the war ended and provided much needed protein as meat was prohibitively expensive and beyond our means. We needed money and reluctantly I was often asked to select one of my precious capons for sale. I recall waking up early in the morning, selecting the doomed chicken who was placed squawking loudly in a bamboo cage. My brother accompanied me on the long miserable walk to Mongkok market where we found a suitable spot to display our ware. We had a Chinese weighing machine "a ching" which was a device made up of a stick with a weight at one end and a hook on the other; the poor fowl with its feet bound would be weighed upside down to determine its weight and value.

There was an incident when a worker next door stole one of my chickens and I marched over to a Japanese soldier at the end of my street reporting the loss – the chickens were such an important asset and my sensibilities were already so dulled that shooting the robber did not seem too harsh a retribution.

Joyce Golding recalls "my mother and I went over to see Julia and we were invited to stay for lunch – there were 8 of us in all and we had 2 eggs to share between us. The eggs were beaten for ages in a large bowl to increase the volume of air thus producing a larger omelette which could be divided between us. We ate it with "sung ko" which was Chinese bread; what a luxury that was and I will never forget how much we enjoyed such a simple meal."

There was no money or means to earn a living and finally my mother had to resort to selling her jewellery. Whenever we needed money to purchase food, we went to various jewellery shops in Mongkok with a selected item to sell. I watched as the jeweller scraped the precious metal onto a black stone, then dropped acid to determine its value and we were given money in exchange – of course outrageously less than its real cost, but we had no choice in these desperate times. Inflation and shortage of supplies was a constant battle and each time we sold an item of jewellery, we headed immediately to the market to purchase rice and non-perishables – dried noodles, dried fish and whatever canned food that was available.

The quality of rice was poor, mostly unpolished red or "broken rice" which contained weevils and when cooked tasted of grit – one reason why these days I am unable to stomach brown rice. Sweet potatoes were cheap and in abundance, so was soya bean and coupled with a few vegetables grown in our garden we survived with mostly empty stomachs for four years.

I recall regularly going over with Bobby Remedios and Lionel Houghton to collect our sporadic ration of rice from the Macau Government. The distribution point was Club Lusitano on Ice House Street. On one occasion, whilst walking past King's Theatre in Hong Kong, we came across three Japanese wearing red sashes denoting their rank as Sergeant-Majors who had a terrible reputation for cruelty. Looking like a bedraggled trio from the slums, we tried to make a wide detour to avoid confrontation but were stopped with a shout. They randomly selected Bobby who was then told to approach and stand to attention. The soldiers then proceeded to berate him for a good fifteen minutes, thankfully Bobby had the presence of mind to bow his head as the ranting continued unabated. We expected to be arrested and thrown into one of the infamous detention centres as we heard some POWs had escaped and they might have thought Bobby was one of them as he looked like his brother Luigi who was interned at Sham Shui Po camp. Thankfully they eventually motioned all three of us to walk off, our hearts pounding at this close call.

Our preoccupation with food was punctuated by breaks playing outside with my brother Bosco in the neighbourhood park. My fading memory recall these dear friends – Lionel and Danny Houghton, Bobby Remedios, Carlos Remedios and Chappy Remedios.

Adults used to amuse themselves with the popular game of mahjong which helped to pass the time. I was beseeched to play as there was a shortage of "legs" to make a foursome so in a matter of time I quickly learnt the skills of this intriguing game.

On one occasion in 1942, a few of us snuck over to the Yvanovich home in Soares Avenue to listen to the radio which we knew would be broadcasting the World Series baseball game between the Yankees and the Cardinals. In those days Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio were household names and many of us became passionate Yankee fans in the late thirties. It was illegal to have a shortwave radio and discovery would have been certain imprisonment. We took our chances, closed all windows and drew heavy curtains, Through the low static we listened in rapture and, despite the Yankees' loss, we felt a small victory in being able to get away with using a short wave radio against the Japanese command.

THE KEMPETAI AND COLLABORATORS

The diminished Portuguese community who remained in Hong Kong had to live under rigid Japanese military rule and, as civilians, many would remember with dread the Chinese collaborators working for the Kempetei who were equivalent to the German Gestapo. These collaborators wore "lai chee vut" which was a black shiny fabric and a white panama hat as its uniform. They were easily identified, and residents in Homantin would recall with fear the appearance of these collaborators who came to interview and arrest third nationals, mainly Portuguese citizens residing in the area. The Japanese believed that many of the Macaenses were working undercover for British intelligence operating as the British Army Aid Group (BAAG).

Once arrested, the victims were taken away to be detained in unknown locations where they were further interrogated and tortured (using the infamous Japanese water torture method) to extract information. The arrested were not given the rights or protection of prisoners of war under the Geneva Convention and their families had no means of locating where the detainees were held. The most feared of all these collaborators was the notorious George Wong.

These members of our community who were incarcerated by the Kempetei do not appear in any Roll of Honour. They were tortured and placed in prolonged solitary confinement while detained on the suspicion of assisting the Allied cause. They were tried in secrecy in Japanese military courts with no representation and received sentences ranging from a few short years to 15 years which were served in Stanley Prison. Finally, the end of the Pacific War intervened and they were freed in August, 1945 except for Henry Basto and Filipe "Pito" Yvanovich who died in captivity. In my fading memory, I recall some of the individuals who were imprisoned; others may be able to expand on the list. Many of these good people are deceased and include:

José Alvares, Jack Alves, Henry Barros, Eduardo Basto, Henry Basto, Fernando Remedios, Francisco "Paco" Remedios, Marcus do Rosario, Ed da Roza, Marcus Silva, Luigi Sousa, Filipe "Pito" Yvanovich, and son Bill "Avichi" Yvanovich.

George Wong who was instrumental in arresting Marcus Silva during the occupation, faced a reverse situation in 1946 when Marcus Silva, as Crown Prosecutor, was involved in the War Crimes Tribunal when collaborators were tried. George Wong was found guilty of war crimes and was subsequently hanged in Stanley Prison.

Those who died in captivity were:

"When the Japanese invaded Hong Kong in 1941, the Club Lusitano was turned into a defence center by the Hong Kong Volunteers. The Japanese were very suspicious of the club's activities and periodically made surprise raids or visits and took members away for interrogation and imprisonment. On one such visit the then President, Henry Basto, and some friend\Whiling away idle time by working out theoretical games of bridge. The Japanese commander saw the notes of the bridge hands and was convinced they were a secret code. Henry Basto was tried for espionage, imprisoned and later beheaded".(Jorge Forjaz Famílias Macaenses Vol 1 p482 Fundação Oriente 1996)

Pito Yvanovich – died in Stanley Prison.

Manuel Prata was a member of the HKVDC and a POW having survived the fighting in Hong Kong.

"He was a member of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps and was arrested and taken away by the Japanese Kempetei from the Argyle Street Prisoner of War Camp accused of being a secret British Army Aid Group liaison team operating in the camp to assist British Prisoners of War to escape to Free China. He was tortured and then executed by the Japanese in Stanley Prison. His name also appears in the British Army Aid Group of Roll of Honour."(Jorge Forjaz Famílias Macaenses Vol II p1100 Fundação Oriente 1996)

THE PRISONER OF WAR CAMP (POW)

The battle for control of Hong Kong lasted 18 days and we had no idea of the whereabouts of my uncles and were fearful of the constant bad news of heavy casualties. Soon after New Year's Day 1942, unknown to us, the British POWs were ferried across to Halt's Wharf, Tsim Sha Tsui and then marched through Nathan Road to be interned at Sham Shiu Po Camp.

It was only when the marching column reached Mongkok that we became aware of this transfer of POWS to their internment at this camp which was a pre-war army barracks. The older residents of Homantin rushed out to Nathan Road returning to give anxious relative the news of survivors. I was peeved at not being allowed to go but relieved to learn that both our uncles were spotted; our prayers had been answered.

In the beginning security in the camp was lax and some POWs managed to escape but the Japanese soon tightened the noose and escapes were rare and met with severe retribution for the internees.

We were occasionally given permission to send letters and food parcels of whatever we could spare. The Japanese designated the date for parcel delivery and we had to arrive by 9 am at the camp which meant that my mother, Bosco and I had to walk some five miles to get to Sham Shiu Po. This was a challenge in our weakened physical condition as we had to have the energy to walk back to Homantin, but a glimpse of our uncles on the other side of the fence made each expedition worthwhile.

Letters were limited to a few words and censored, sentences cut out arriving like confetti. All parcels were scrutinized carefully, cakes were cut as the guards looked for weapons, radios or hidden messages. We received letters from my uncles in 1944 requesting large supplies of brown sugar or "wong tong" in Cantonese which came in slabs. We later found out that the sugar was made into toffee and our uncles had started an enterprising business in camp which helped them to exchange their toffees for small luxuries at the camp.

My mother was secretary to John Fleming who was senior partner at Lowe, Bingham and Matthews before her marriage. During the Japanese occupation, despite extreme hardship, she managed to send occasional food parcels to her old boss who she learnt was at Stanley internment camp which was for Allied civilians. After the war in gratitude he personally arranged for my father Charlie to return to Hong Kong from Shanghai with a position with Lowe, Bingham and Matthews.

The Japanese used the POWs as forced labour to extend Kai Tak Airport, marching prisoners at the crack of dawn along Nathan and Prince Edward Roads toward Kowloon City. On these occasions residents would rush out onto the streets to catch sight of loved ones, only daring a furtive glance or nod in acknowledgement.

In early 1945, again the POWs were forced to dig tunnels to hide food and ammunition for the anticipated allied counter-invasion. The tunnels were located underneath Diocesan Boys' School and we managed again to catch a glimpse of our uncles and their inmates from the advantage of Kadoorie Hill which overlooked the tunnels. Their physical deterioration was obvious after enduring four years of starvation and hardship and caused us great concern. We prayed continuously for deliverance as hope of an impending allied victory filtered through.

After the war in 1945, a huge explosion occurred in one of these tunnels which rocked Homantin and covered many homes in a layer of mud. It is believed that looters entered the tunnels in an attempt to pilfer goods and the place may have been booby trapped resulting in the conflagration. My father commented that it was the loudest explosion he had ever heard and the resulting inferno was a topic of conjecture for days.

THE POST WAR YEARS

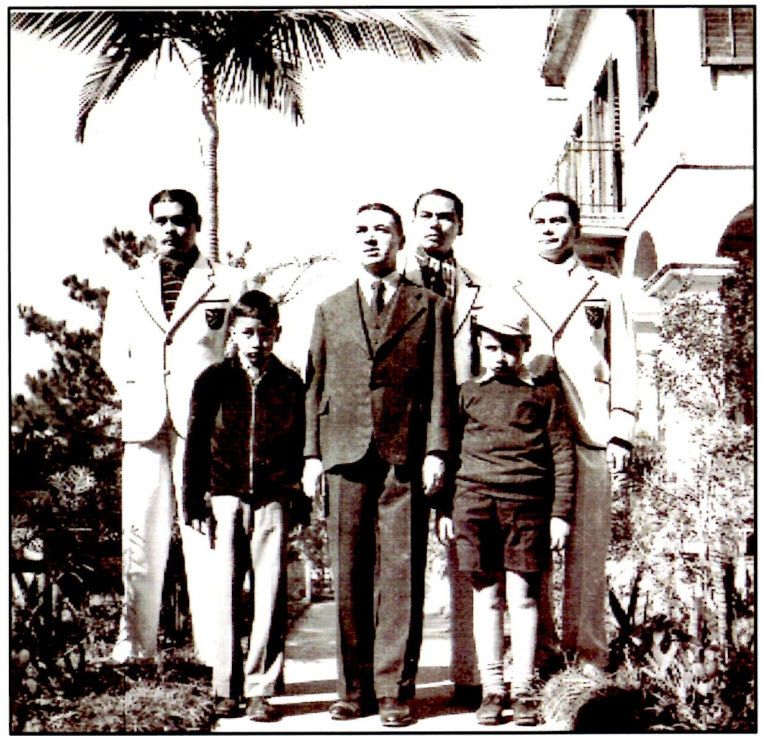

Our family was joyfully re-united after Liberation Day, 31st August, 1945.

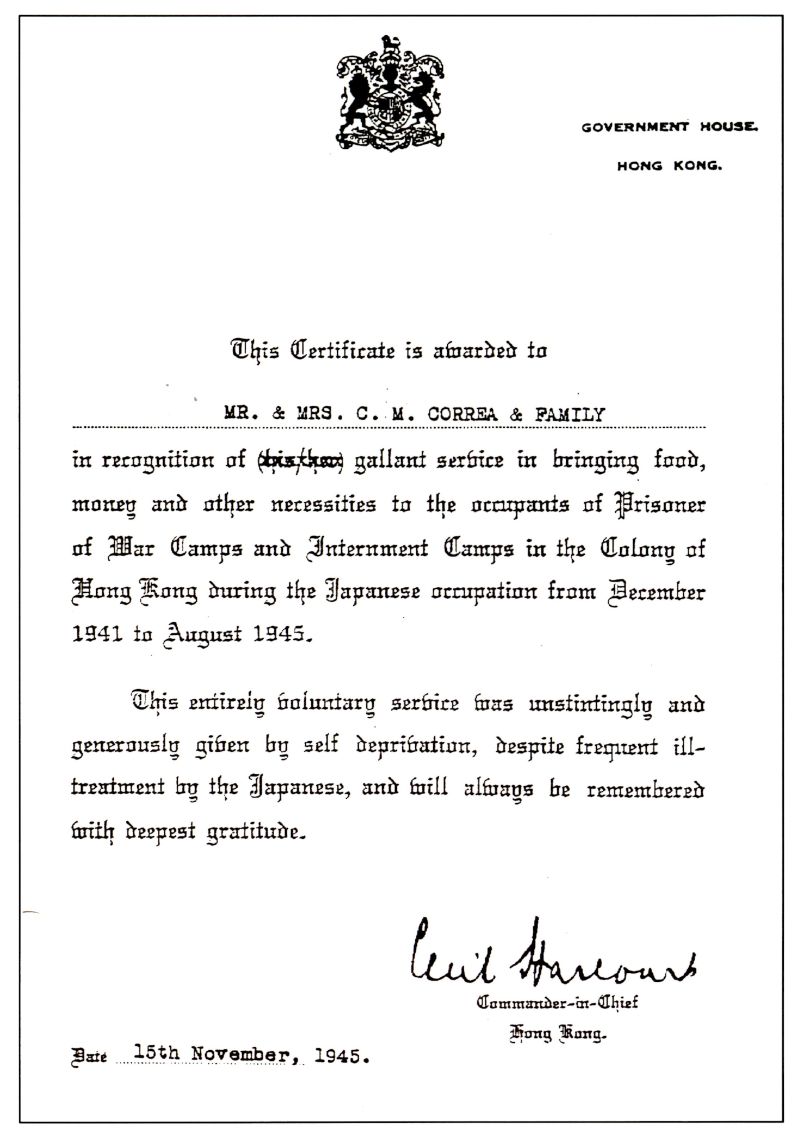

Uncles Mem and Luigi were de-mobbed and returned home looking emaciated with many stories to relate about their war experience. In November my father finally returned from Shanghai after a separation of four years. We were given a special citation from the British Government for services to the Allies.

My father lived in Shanghai during these years with his widowed mother Wilhelmina who had re-married Charlico Pereira who owned a wholesale coffee business. They lived at Avenue Joffre in the French Concession and managed to survive with income from the coffee business. Dad's sister Auntie Sofie helped in the shop which roasted its own beans on the first floor and cousins Elvie, Stella and Oscar also lived there as they were separated from their father Tony who was stranded in the Philippines. My father eventually lost his job at Bristol Myers as businesses closed down with the Japanese occupation but fortunately managed to find work at Club Lusitano as its Secretary and Accountant.

There were shortages of everything but we felt fortunate to have survived with our family intact. My father, as promised by John Fleming, returned as soon as possible, beginning work with Lowe Bingham and Matthews but later securing a better position with E. Ott and Company as Chief Accountant. This was a Swiss Trading Company and we were given housing as part of the contract so the Correa family moved nearby to 93 Waterloo Road to a two-storey house. Uncle Mem came along and stayed with us; by then he was working for the Hong Kong government. My father worked in this company until he died suddenly of heart failure on 11th January 1954 when I was 23 and Bosco 21.

2 Liberty Avenue was eventually sold. Grandfather, because of his old age, was accommodated by the Little Sisters of the Poor who had a home for the aged near Clear Water Bay Road. He passed away aged 85 on 25th June 1953.

Our family was sustained by our Faith, Christianity bestowed by our forefathers when they established Portuguese colonies in their voyages of discovery. The Gospel of Christ and His teaching was and continues to be the foundation of the values of the Macaense diaspora who are now found in the far-flung corners of the globe.

In our despair "the light shone in the darkness" giving us hope. I recall the priest reading from Psalm 27 which was of great comfort:

In diminished numbers we worshipped at St. Teresa's Church in Prince Edward Road surrounded by white urns of Japanese soldiers who had been killed then cremated and kept at the church as a sacred site. These urns were eventually respectfully returned to their relatives in Japan.

Thus, our community both in Hong Kong and Macau survived the four years of the Second World War, their Faith strengthened by the adversity which they endured.

I had missed so much of my education with no schooling for four years. My peers who went to Macau were far more fortunate as the Hong Kong Jesuits established a school there with a British curriculum. As soon as the war ended the Jesuits returned and restarted Wah Yan College on Hong Kong island and the students from Macau who returned immediately began their classes in January 1946.

Fortunately, I was accepted into Class 3 at Wah Yan and had a difficult time catching up with the others. I had to wake up at the crack of dawn to attend school having to walk to Mongkok to catch the ferry and then climb up to Robinson Road which was in the mid-levels. Thankfully after six months the Christian Brothers returned and re-opened La Salle College in Boundary Street and all of us residing in Kowloon transferred back to our old school.

I was a diligent student and managed to catch up, achieving good marks in matriculation and was nominated for a government scholarship to attend university. Unfortunately this did not materialize as the previous year several Portuguese had gained entry into Hong Kong University and it was decided to award scholarships to Chinese nationals instead. This was one of my greatest disappointments in life as I had a keen interest in civil engineering. I still have the letter my father wrote explaining that he could not afford university fees and offered a job placement instead at Peat Marwick Mitchell.

Everything changed in Hong Kong after the turbulent war years – political uncertainty with the communist takeover of China, the Korean War, large influx of refugees, riots, the Vietnam war. Our community began thinking of migrating to other countries seeking security and better opportunity. My mother was reluctant to consider this option although it was mooted briefly after my father died.

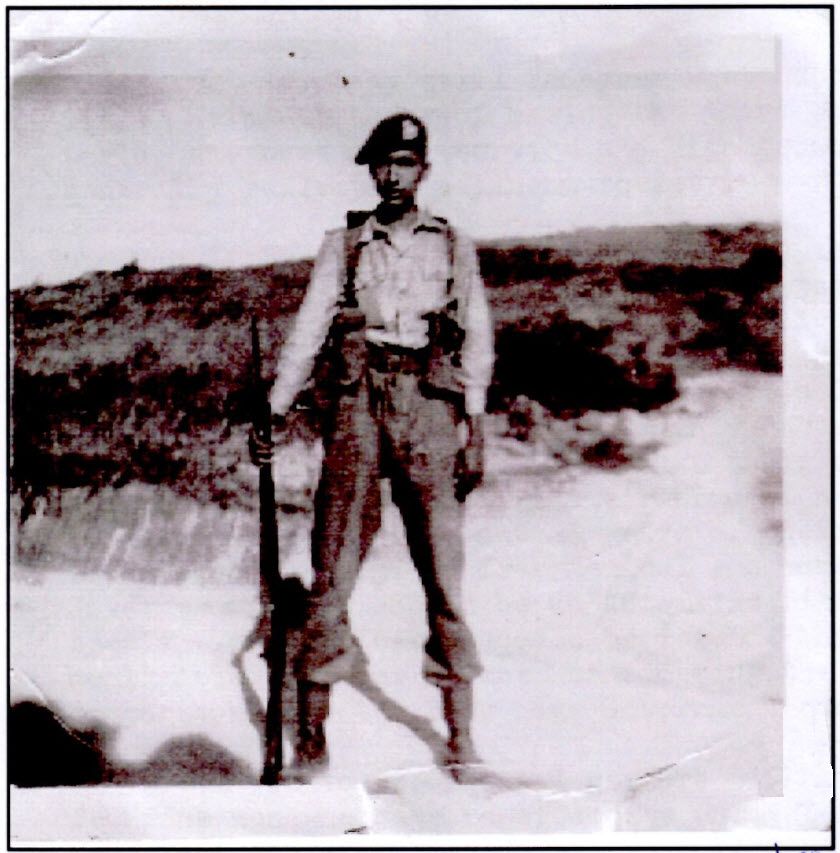

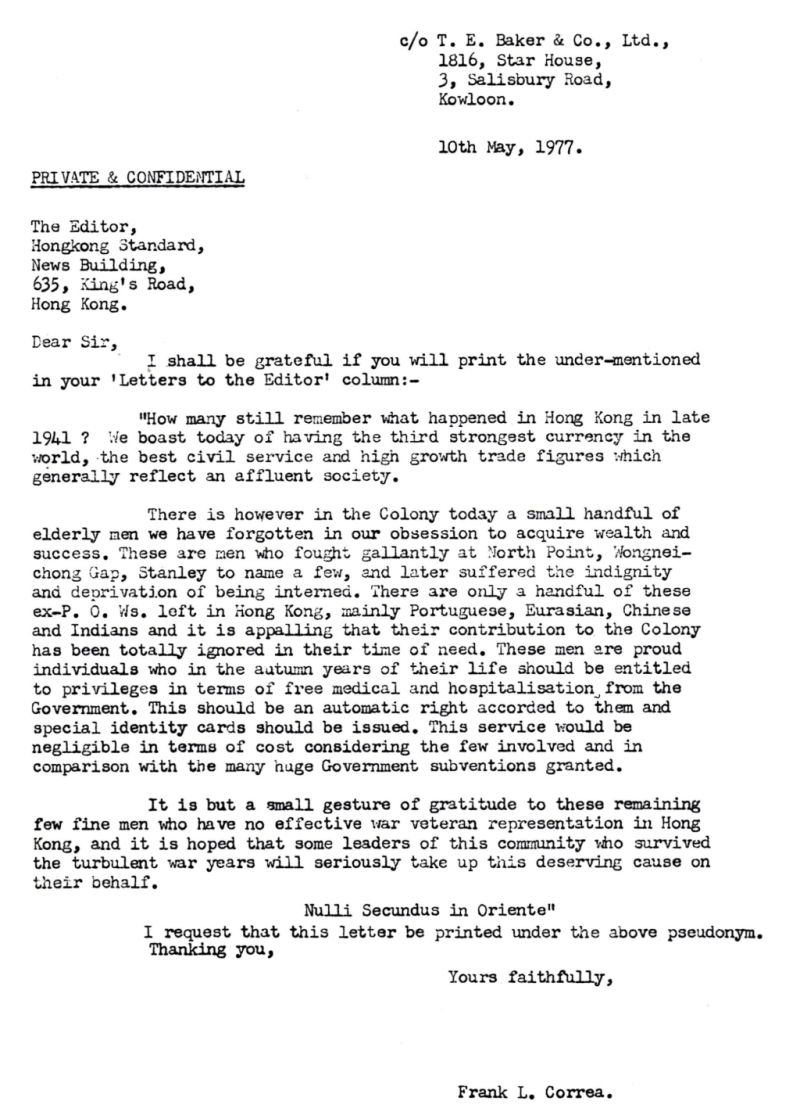

In keeping with family tradition (my father was a Sergeant in the Shanghai volunteers), I also joined the Hong Kong contingent, serving seven years as a lance-corporal. When I returned to Hong Kong after living several years in Australia, the unequal treatment of the local contingent compared to the British counterparts compelled me to start a campaign for equal rights for the local POW volunteers. Several letters were published in the South China Morning Post and Hong Kong Standard newspapers bearing my pseudonym "Nulli secundus in Oriente" which is the motto of the HKVDC. The issue was taken up by Editorials and other locals. Eventually the government gave POWs a pension and free health care, privileges long enjoyed by their British counterparts. Unfortunately, my uncle Mem passed away from kidney failure without ever enjoying these benefits.

Whilst with Peat Marwick and Mitchell, China Light and Power offered me a better position in their accounts department and I worked there for fourteen years. Life was comfortable living at 114 Boundary Street with my mother, brother and Uncle Mem. Weekends were spent coaching softball or boating with the Vieira family in a pleasure junk in Sai Kung.

In 1967, I was asked to attend a Hong Kong Regiment volunteer's annual ball at the Peninsular Hotel and did not have a partner. Miraculously, this elegant and vivacious young woman, aptly called Vivi, somehow agreed to come with me on a blind date. It was "one enchanted evening" followed by a whirlwind courtship, marriage and immigration to Australia in a year. We have been married for forty one years and blessed with four wonderful children – three sons, Anthony, Michael, Peter and a daughter Joanna. Our lives have been a never-ending astonishing escapade but that, of course, is another long story.

In keeping with family tradition (my father was a Sergeant in the Shanghai volunteers), I also joined the Hong Kong contingent, serving seven years as a lance-corporal. When I returned to Hong Kong after living several years in Australia, the unequal treatment of the local contingent compared to the British counterparts compelled me to start a campaign for equal rights for the local POW volunteers. Several letters were published in the South China Morning Post and Hong Kong Standard newspapers bearing my pseudonym "Nulli secundus in Oriente" which is the motto of the HKVDC. The issue was taken up by Editorials and other locals. Eventually the government gave POWs a pension and free health care, privileges long enjoyed by their British counterparts. Unfortunately, my uncle Mem passed away from kidney failure without ever enjoying these benefits.

Whilst with Peat Marwick and Mitchell, China Light and Power offered me a better position in their accounts department and I worked there for fourteen years. Life was comfortable living at 114 Boundary Street with my mother, brother and Uncle Mem. Weekends were spent coaching softball or boating with the Vieira family in a pleasure junk in Sai Kung.

In 1967, I was asked to attend a Hong Kong Regiment volunteer's annual ball at the Peninsular Hotel and did not have a partner. Miraculously, this elegant and vivacious young woman, aptly called Vivi, somehow agreed to come with me on a blind date. It was "one enchanted evening" followed by a whirlwind courtship, marriage and immigration to Australia in a year. We have been married for forty one years and blessed with four wonderful children – three sons, Anthony, Michael, Peter and a daughter Joanna. Our lives have been a never-ending astonishing escapade but that, of course, is another long story.

Hetty's Story

The village of Homantin lay several miles northeast of Tsimshatsui in a stretch of rural land nestling within gentle hills. The Hakka farmers who lived there were content, the soil fertile and productive, their vegetable plots so symmetrical they looked like quilts spread out in the sunshine. Swathes of greenery swept across the landscape filled with a∑ wondrous variety of fruit trees, shrubs and tropical flowers, notably soft scented Camellias and red-blood Hibiscus that enhanced the idyll of Homantin.

In the intervening years a scattering of urban houses and flats sprang up in rural Homantin populated by middle-class Macanese families who lived in companionable harmony alongside the local farmers and bought their produce – eggs, vegetables and fruit. However, the exuberant escapades of the children of these families during the school holidays exhausted the farmers' patience. As evening cast its shadow over the land the children crept surreptitiously into their orchards bent heavy with fruit and plucked them. Chins dripping, they scurry away like rats when detected, skilfully avoiding the open pits of night soil in their hasty retreat. The hapless farmers were, of course, no match for the nimble youngsters who subsequently regaled their friends with exaggerated stories of near capture.

This idyllic way of life was shattered when the Japanese attacked Hong Kong on the morning of 8th December, 1941. Out of the clear blue sky aeroplanes swooped down at tree top level raining bombs on Kai Tak Airfield, Kowloon. Japanese planes strafed the Shamshuipo Barracks, the Police Station and nearby residential buildings then continued south towards Hong Kong Island bringing in their wake rampant death and destruction. Thus the citizens of Hong Kong were faced with the grim reality that nothing would ever be the same again; their world as they knew it had disintegrated overnight.

The aftermath of the aerial attack on Hong Kong and Kowloon created monumental chaos. People panicked and within a matter of days, rice, tinned goods and fresh meats and vegetables vanished from stores and market stalls. Residual canned goods could be purchased at extortionate prices.

A deceptive calm descended over the ground floor flat of No.23 Homantin Street. In the hush of dawn the crushing events of 8th December seemed remote and unreal save a lingering sense of unease that hovered like slow death upon this once peaceful and beautiful hamlet of Kowloon.

Hetty had always been an early riser, a routine that stemmed from her Convent days as a schoolgirl.

She drew back the curtains to let in the morning light and the window reflection of a Flame of the Forest tree in the garden that from February to April proliferated in a canopy of scarlet blossoms on the upper portion of the tree, luscious and magnificent, giving the appearance of a tree afire. Hetty is happiest in the garden. She is a woman who loves the smell of freshly cut grass, the coolness of morning dew, the exquisiteness of asparagus ferns of arching branches.

It promised to be another mild December day. Hetty dressed with care and wore a short sleeve cotton dress of blue and white flowers then added a delicate gold watch that glinted on her wrist. She gazed down at her infant son asleep in his cot and smiled, wistfully stroking his soft cheek so that he stirred and opened his sleepy eyes a second then closed them again.

A serene woman, she took pride in the notion that she had married ">Arthur, a Marine Engineer, a loving husband and devoted father to their four children: Shirley, twelve; Gerald, eleven; Hilda, eight; and, lastly, Arthur an infant of seven months and a miniature version of his father with wisps of black hair and eyes as dark as iris blossoms.

The family led a charmed life, lived in spacious accommodation, owned a car and employed servants to help with the general running of the household.

Hetty went from room to room to check on her children as they slept. Gerald had his own room. Leaning against one side of the wall was his beloved Phillips bicycle, a present from his father on his tenth birthday. He loved it dearly, and kept it in pristine condition, oiling its chains with meticulous care so that it was always primed for rides to La Salle College at Boundary Street. But those halcyon days were gone with the wind and her son could no longer cycle to school or play with his classmates in the green fields and gentle hills that surrounded Homantin.

It was an extraordinary time, a time of great trepidation especially for tens of thousands of women whose husbands had left home in defence of King and country. Suddenly women from all walks of life were left to fend for themselves and raise their children alone without protection or money. Hetty was among the unfortunate majority, her husband was already at sea in the Merchant Navy at the outbreak of hostilities and for the first time since their marriage she felt fear at his absence.

There was something subtly different about the morning, it wasn't anything palpable she could see or touch, just an echoing silence that pervaded the atmosphere. The absence of familiar sounds, the tinkling of teaspoons against china teacups and the clattering of cutlery, unsettled her. Hetty stepped into the dining room and looked around, no one was about. Passing through the passage to the kitchen conscious of her own footsteps on the polished floor, she was surprised to find the servants' quarters deserted except for a detritus pile of discarded clothing, rusty hairpins, a pair of old clogs and a broken comb with tangled hair clinging to it. She could no longer ignore the gloom that infected her tinged with something very close to fear.

She went in search of Ah Ng, her loyal servant and general factotum, calling out her name. There was no response. An uncomfortable thought crossed her mind. Could it be that Ah Ng had left as well? Her heart beat faster. She re-traced her steps, opened wide the long windows of the dining room that led to the porch and the back garden. In a wedge of light from the half open door of the garden shed she recognized the figure of Ah Ng hunched over something she could not quite discern. With instant recognition a positive sense of relief overwhelmed her. Ah Ng had not left!

She approached her servant "What are you doing?" she asked, her soft voice quivering with curiosity. Ah Ng spoke only Cantonese, the indigenous language of domestic servants in Hong Kong at the time. Being Macanese (Portuguese from Macao), Hetty understood her language well.

"I have wrapped your British Passports inside this oil cloth" Ah Ng replied, lifting a tidy packet tied with string to show Hetty. "I will hide this in the urn of manure," she explained. Then hesitating a moment as if contemplating the wisdom of her next disclosure she continued, "My people they say things not good for the British and soon Japanese they march into Kowloon." The Chinese were better informed than most of the progress of the battle raging in Gin Drinkers' Line in the New Territories. Their ubiquitous "bamboo radio", its ripple effect like stones dropped into a pool spread in ever increasing circles, the news echoing out – word-by-word, minute-by-minute.

"When the Japanese come, and they will come," Ah Ng asserted, "they will search your house. If they find your British passports, you will all be thrown in jail but they will not look in here," she chuckled, pointing to the urn of night soil, the absurdity of its spurious location appealing to her sense of humour.

"Did you know that Ah Mui and Ah Sing have run off? For one terrifying moment I thought you too had abandoned me." Hetty whispered, close to tears.

"No Missy, I will never leave you not while the Master is at sea" Ah Ng replied reassuringly. She was fond of the family. She lived with them, helped run a household, cooked and served them meals, brought up her own child within the shelter of the household and eased the three elder children into sleep in earlier years, she knew the character of all of them as well as their parents.

On 12th December cocooned in the relative safety of her home, Hetty dressed early with the intention of paying her utility bills and queuing outside the bank to draw money.

"Ah Ng, will you look after the children while I go to the bank?" Hetty asked.

Ah Ng stared at her incredulously, the woman must be mad she thought. 'No, no, you mustn't leave the house,' she insisted, 'It is very dangerous outside. The British they run away to Hong Kong side. No more policemen in streets to help you. Looters run around like crazy with choppers and knives. They will surely rob or even kill you. " Hetty noticed the inflection Ah Ng had placed on the word 'Kill,' miming the slitting of her throat and secretly wished she would refrain from theatricalities that frightened her.

"But what will happen to us?" Hetty wanted to know unable to keep the alarm out of her voice. "I must draw money from the bank, stock more food and buy milk powder for the baby," she insisted.

"Have you got any money in the house?" queried Ah Ng.

Hetty nodded.

"How much?"

"About HK$350."

"Better you no go alone, we go together. We take children with us."

Returning to the house still concerned over the need for extra cash, the women set about preparing the children's breakfast. With the future uncertain and fraught with danger, the thin thread, fragile as gossamer, between mistress and servant disappeared altogether. They were just two women dependent on one another in their struggle for survival.

Whilst discussing ways and means of coping with their dilemma, an ominous sound like the deep rumble of thunder could be heard from the street outside. The noise grew in intensity until it reached a deafening crescendo of wild shouts and screams.

"What's happening?" Hetty turned to Ah Ng trembling. The children, sensing their mother's fear, clung to one another.

Ah Ng was a formidable woman who had lived through difficult times and though somewhat too direct and tactless for a domestic she was, nonetheless, indispensable in a crisis. Her pragmatism and innate commonsense were about to be sorely tested.

Tramping footsteps reverberated along the corridor and Ah Ng knew instinctively that looters had arrived at their doorstep.

Thereafter everything happened in swift rapidity. She shouted to Hetty to take the baby and hide then, grabbing Hetty's handbag from the sideboard in the parlour, she removed the dollar notes and stuffed these into the hidden pocket of her black trousers. Hurriedly, she thrust the handbag under the cushion on the sofa then, composing herself, she smoothed down her white shirt with her hands, patted the bun at the back of her head and gathered the children around her coaxing them not to cry.

The inevitable happened. The front door was in danger of being smashed to pieces under the heavy hammering. Amid the rising hysteria Ah Ng implored the looters not to smash the door down. She was going to unlock it. Immediately she opened the door, she was pushed aside unceremoniously by a band of six looters armed with choppers and knives.

"We want money now!" shouted their leader, an obnoxious swarthy coolie turned looter, his predatory eyes dark as a coal pit and equally as cold.

He began by mouthing obscenities at Ah Ng, sweat shining on his forehead. "Where is your mistress?" he demanded, dark eyes smouldering.

"She is away and I am looking after her children for her," Ah Ng replied calmly.

The silence was absolute and he sensed she was lying which incensed him. In a flash of rage he grabbed a crystal vase on the sideboard and hurled it. Shards of glass rained down the bare wall. This irrational behaviour served somehow to placate his appetite, at least temporarily, from further histrionics. He ordered his men to search the premises. Amid much slamming, opening and shutting of cupboard doors, broom cupboards, and other possible refuges, they soon found Hetty cowering in the walk-in larder clutching her baby. Two looters manhandled her into the sitting room. At the sight of their mother the children started wailing partly in relief but mainly in fear.

Time was optimum for the looter who made no attempt to conceal his impatience. Suddenly he seized Shirley from behind in a tight grip around her neck brandishing a chopper to her throat, his breath stank. Shirley swallowed hard and shut her eyes.

"Either you show me some money or I'll slit her throat." He threatened the women menacingly.

Ah Ng watched helplessly enduring with cold rage the bullying tactics of this menacing looter. On the verge of answering belligerently, she paused. She noticed the abject terror in her mistress's eyes and with a resigned gesture pointed to the sofa. The looter tossed the cushion aside, rummaged through the leather handbag and withdrew a stack of envelopes. He ripped open the envelopes; inside were twenty-dollar notes reserved for utility bills. Pocketing the money, he tossed the envelopes in the air, littering the floor. "More," he roared, "you must have more!"

"Get out that's all we have," Ah Ng shouted back defiantly unable to restrain her pent-up anger any longer. She knew, from his accent, that they came from the same village across the border and she reminded him of this fact amid a torrent of vituperation.

For a second the looter stood stock-still stunned by the audacity of her tirade then, tilting his head back, he laughed long and hard, he liked a woman with spirit and had met his match in Ah Ng.

However, the looter had more pressing business at hand, the business of robbing defenceless civilians. Satisfied that there was no more cash or jewellery in the flat, he turned to Hetty and was about to snatch the gold watch from her wrist when he met Ah Ng's contemptuous gaze and stopped. The looters finally left en masse slamming the door behind them, their receding voices raving and ranting in the distance.

Their sudden encounter with the looters left Hetty so traumatised that she did not have the strength to hold the baby properly as he fidgeted and whimpered like a puppy. She handed him to Ah Ng and groped unseeing for the sofa, her legs beginning to give way. Slowly, she sank into the solace of the sofa. It was then the silent tears cascaded down her cheeks, trickling on to the hands that were now trembling in her lap. Sensible for her young years, Shirley handed her mother a handkerchief and held her tightly.

Several hours later with calm restored, Hetty telephoned her longstanding friend, Mrs. Camilla Brown, and recounted the family's harrowing experience. Camilla told her to pack a suitcase, leave the flat immediately, and proceed to the residence of the Portuguese Consul, Mr. Francisco Soares at No.2 Liberty Avenue. She explained that scores of women in similar circumstances had abandoned their houses and taken refuge in the Consul's house on the premise of safety in numbers. Hetty thanked Camilla and began packing immediately.

In the bedroom the two women attempted to deal with the bewildering and difficult task of working out what to take. They spread the bed linen on the floor and selected a few pieces of essential clothing tossing these into the sheet then, gathering the four corners, tied a knot at the top to secure the clothes inside. Hetty retrieved the family's passports and collected her jewellery that lay hidden in the false bottom drawer of the dresser in her bedroom and vacated the flat forthwith.

Hefting the cloth bundle over her shoulder like a dispirited refugee, Ah Ng accompanied Hetty and her children to the Consul's house situated in a prestigious area of substantial detached houses. Mr. Soares, the Portuguese Consul, welcomed them although the extreme weariness in Hetty's eyes did not escape his notice. They were shown into a large reception room that held an inordinate number of men, women and children.

Some people were sitting or lying on mattresses that skirted the edge of the room and others were chatting in small groups out on the veranda. Reluctantly, she released Ah Ng's hand turning her face away from her gaze, tears very near the surface. Inherently taciturn, shy and diffident, the prospect of living in propinquity with complete strangers for an indeterminate period filled her with dread. Ah Ng promised she would visit soon then disconsolately left without a backward glance.

Hetty's encounter with the harsh reality of communal living began on her first evening in the Consul's house. Her children slept in their clothes over mattresses on the floor. Food, a vital commodity in wartime, was rationed carefully. The children were hungry despite having eaten their quota of horsemeat in a bowl of soggy rice only a few hours earlier. Little Arthur, normally a placid baby, began to cry relentlessly.

From somewhere in the vast communal room a repugnant Macanese young man, who should have known better, shouted: "Can't you keep that brat quiet?" his strident voice thundered across the room.

Loath to draw attention to herself in a place where people live in the midst of fear, where conflict becomes a part of everyday living, Hetty gathered little Arthur in her arms and ran towards the gazebo in the back garden. It was frightening. There seemed no way of quelling his pathetic crying. She paced up and down the garden path rocking him in her arms until he fell asleep from sheer exhaustion.

The light was changing: evening deepened and darkness filled the garden. A soft wind swayed the aerial roots from the trunk and branches of the banyan tree. In the gazebo Hetty sat motionless staring vacantly into the darkness with little Arthur fast asleep in her arms.

Alone with her thoughts she felt her heart grow heavy. She wondered whether she would ever see her husband again. She needed to share her worries with him but he was not there. She tried to imagine what she would do if he did not come back. Perhaps she could get a job teaching, but the main thrust was not about looking after herself and the children it was the notion of being without Van – her pet name for her husband – indefinitely. She could not live without him.

The following afternoon when Ah Ng came to visit she was appalled at the dishevelled appearance of her mistress. Hetty had obviously been up all night. The distressing events of the night before compelled the women to come to grips with this untenable situation. They decided that Ah Ng would take the baby to her modest but fortified hut at the foothills of Lion's Rock and keep him overnight with her, returning him to his mother the next day. This unorthodox arrangement seemed, for the interim at least, the best solution open to the women.

Towards the end of January the temperature plunged. On a cold, bright morning Hetty was in the garden hanging out the washing and it was only when she bent to retrieve a fallen peg that she noticed with alarm her handbag on the ground beside her had vanished along with her money and jewellery. She turned around to see if there was anybody about but there was no one in sight. An anguished cry stuck in her throat. The culmination of suffering since the outbreak of war was a lesson in values for Hetty. She learned that she could do without a fine flat, servants, a car, and good food, even un-ironed clothes. With everything she possessed ruthlessly swept away she realised that she could not give way to despair if she wished her children to survive this terrible war.

The Consul was a compassionate man with an impressive ability to master details. It was not long before he heard of the theft of Hetty's handbag and bristled with indignation. He had the deepest respect for this slim, attractive woman, soft spoken and uncomplaining. A former schoolteacher she had a perceptive mind and an unquenchable zest for hard work. He would try his utmost to help her.

One morning he sent for her and when she entered his spacious oak-panelled office he graciously offered her a chair opposite his exquisite rosewood desk. He began: 'Mrs. van Langenberg how would you like to live in Macao? I can guarantee safe passage for you and your children.'

The question startled Hetty, her hands trembled slightly and she gripped the edge of her chair. 'But I haven't any money and what money I had has been stolen from me,' she protested. 'I know of no one in Macao who would provide for my family. Here in your house we feel safe and protected. If I have offended you in anyway or contravened the rules of the house I will make amends" she apologised, the implications of. his question loosening her normally succinct tongue.

The Consul shook his head in astonishment. This was not the reaction he had expected. He saw with amazement and embarrassment that the poor woman was close to tears and had completely misunderstood his kind intention. "No, no, my dear, you misunderstand me' he said, half rising from his seat. 'This offer is for your consideration' he said reassuringly then sat back in his leather chair. 'The women who live here choose to stay because they have husbands or sons interned in Shamshuipo Camp whereas you are free of such commitment. Hong Kong has become an extremely dangerous place to live and I'm not sure how long I can continue to protect the people under my roof," he said tentatively, voicing his thoughts. He paused a moment, then continued: "Every day waves of our people are fleeing Hong Kong for the safety of Macao. The Portuguese Governor is sympathetic to our plight and regards us as one of his own. Your children will be sheltered and looked after by the Portuguese government in Macao. The British Consul resident in Macao, Mr. John Reeve, has access to overseas news and will be better placed to make enquiries of your husband's whereabouts."

Hetty's tension eased. She felt calmer now and accepted Mr. Soares's offer with alacrity, grateful for his kindness. It was with surprise and delight when, on 6th February 1942, she and her four children were accompanied by staff of the Portuguese Consul to the Ferry Boat, The 'Fat Shan,' bound for Macao. Her relief was marred by the necessity of separation from her loyal servant. But Ah Ng had family responsibilities of her own to contend with, a daughter of eight and an elderly mother. However, Hetty clung to the unfaltering belief that somehow, somewhere, they would meet again.

Macao, peaceful and tranquil, was the antithesis of Hong Kong under Japanese domination. Food rations in the refugee Centre were adequate albeit not plentiful. No one starved furthermore it was safe to walk the streets and stroll along Praia Grande in the cool evening air without fear. In answer to her prayers, fresh news soon arrived from the British Consul. Her husband was alive and well. In fact he was commissioned to the rank of Sub Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Reserve that entitled her to a commensurate rise in subsidy. Thus Hetty lived through three long and lonely summers in Macao and raised her four children in relative peace along with other displaced families in a refugee centre.

However, by this time, unconfirmed reports of an allied victory refreshing as the first breath of spring swept over Macao's red roofed houses, cobbled streets and ancient churches. In 1945 Japan capitulated.

One fine day in 1946 a stalwart officer in full British naval uniform arrived in Macao calling at No.16 Rua do Formosa to claim his family. His son Gerald, now 15, glowed with a pride he had never felt before and it seemed as if the buttons of his new shirt (cut out from a tablecloth) would pop, which in reality was not possible because in four years he had grown taller but, at the same time, skinnier and more dishevelled than ever. He held on tightly to his father's hand. It was the proudest day of his young life.

Looking down at him with a smile his father said: "Son, let's go home."

In peacetime Hetty's thoughts strayed variously with a sense of remembered pleasure to the serenity of this Portuguese enclave, possessed of an old world charm and steeped in centuries of tradition that faded with the passing years, never to be recaptured.

This story is dedicated to Mr. Francisco Soares, a man whose compassion, courage and magnanimity saved the lives of many of his people from the ravages of war in Hong Kong and is also a tribute to the thousands of brave, lonely women who lived through it with stoicism.

Hetty was my mother-in-law, a woman of singular compassion, gentility and quiet dignity, greatly loved by her family and all the people who knew her.

In total, four hundred dispossessed Macanese men, women and children sought shelter and protection in Francisco Soares's home at No.2 Liberty Avenue, Homantin, in the dark days of Japanese occupation.