My Wartime Experience

Philippe Yvanovich

An edited version of a booklet previously distributed privately by Philippe Yvanovich. His family has kindly given permission for it to be included in this website.

December 7, 1941

After 10 am mass at St Theresa's I went along to the Club Recreio for a game of hockey and lunch at the Club. Then we sat around watching other sports. At about 4pmAbout 10 hours BEFORE the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour! So British Intelligence must have learned that something was afoot. we received the announcement of the call-up, mobilisation, of the VolunteersPhilippe was a member of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps at Garden Road on Hong Kong (HK) Island at 8am the next day.

I was with Memie Gonsalves, Aboti Silva, Roberto Marques, Tony Alves and Marie Figueiredo, sitting out on the lawn. Then a second announcement that boys who worked in banks did not have to be called up. Memie and I decided we would turn up, Roberto Marques said he would go to work. We all went home early.

December 8, 1941

Dressed in my uniform — khaki long sleeve shirt, khaki shorts, puttees & boots with a change of underwear and a sleeveless woollen (civy)civilian clothes vest — I caught an early bus after a good breakfast and reached the Star Ferry Terminal after 7.30am. When the ferry was midway, we could see the Japanese planes attacking Kai Tak Airport. Getting off the ferry, I walked alone up Garden Path to HeadquartersThe Headquarters of the HK Volunteer Defence Corps . Crossing the parade ground, frantic shouts and signals were made for me to get under shelter of the wooden huts and verandas around the ground.

Now I must digress to explain the setup of the HKVDC. The HK Volunteers was established by The Volunteer Ordinance 1920 and was structured as per legislation of February 1920 as follows:

- 1 Company Artillery

- 1 Company Engineers

- 1 Machine Gun Company

- Battalion of Infantry:

- 1 Mounted Infantry Company (Motorised) Light Armoured Cars

- Motor Cycle Side Cars

- 1 Light Infantry Company (mainly Eurasians) MG Company

- 1 Scottish Company

- 1 (later expanded to 2) Portuguese Co. No 5 Co MGMachine Gun Co.

- No 6 Co. Light AAAnti-Aircraft

- Field Ambulance

- 1 Headquarter Company

- Naval Reserve Company

- Air Reserve Company

I only discovered after the war that my greatgrandfather, Estefan Yvanovich, was one of the "99", when the book Second to None by Phillip Bruce was published in 1991.

The "99" were the group of citizens of Hong Kong who came together to start the "Corps of Volunteers" for the defence of the lives and property of themselves and their families in time of emergency as gazetted on 3rd June 1854.

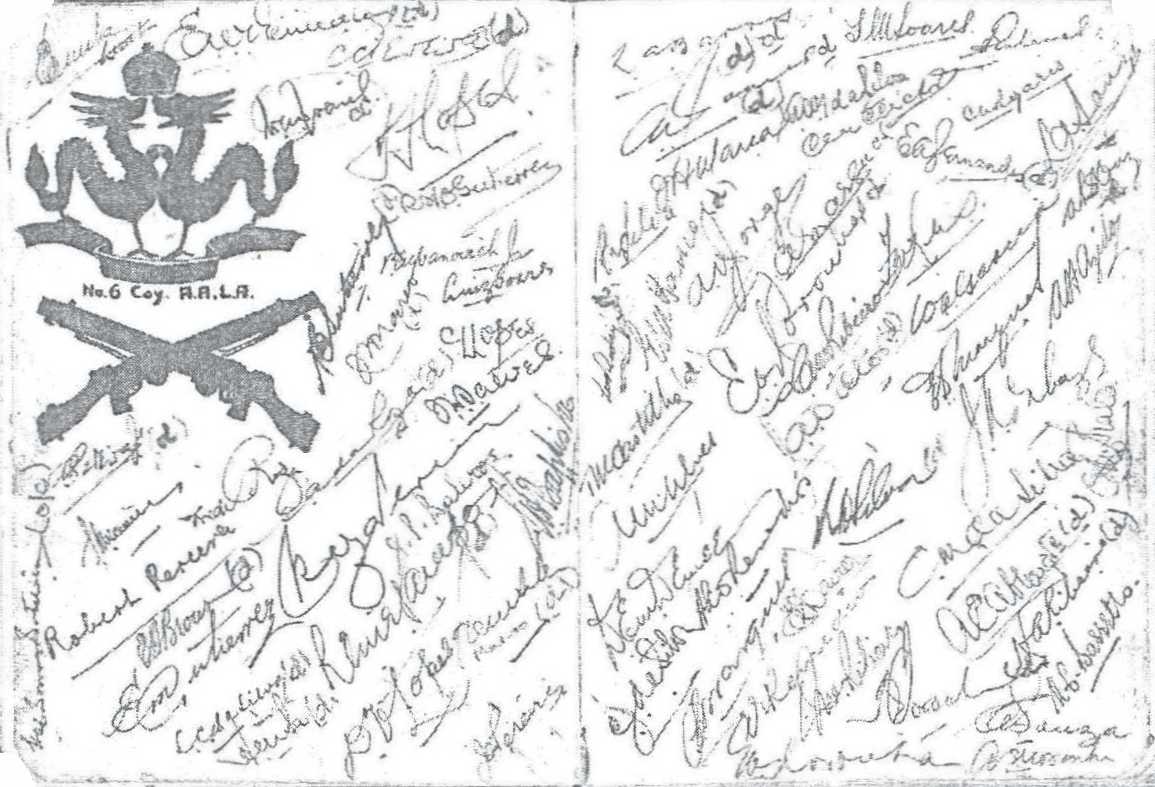

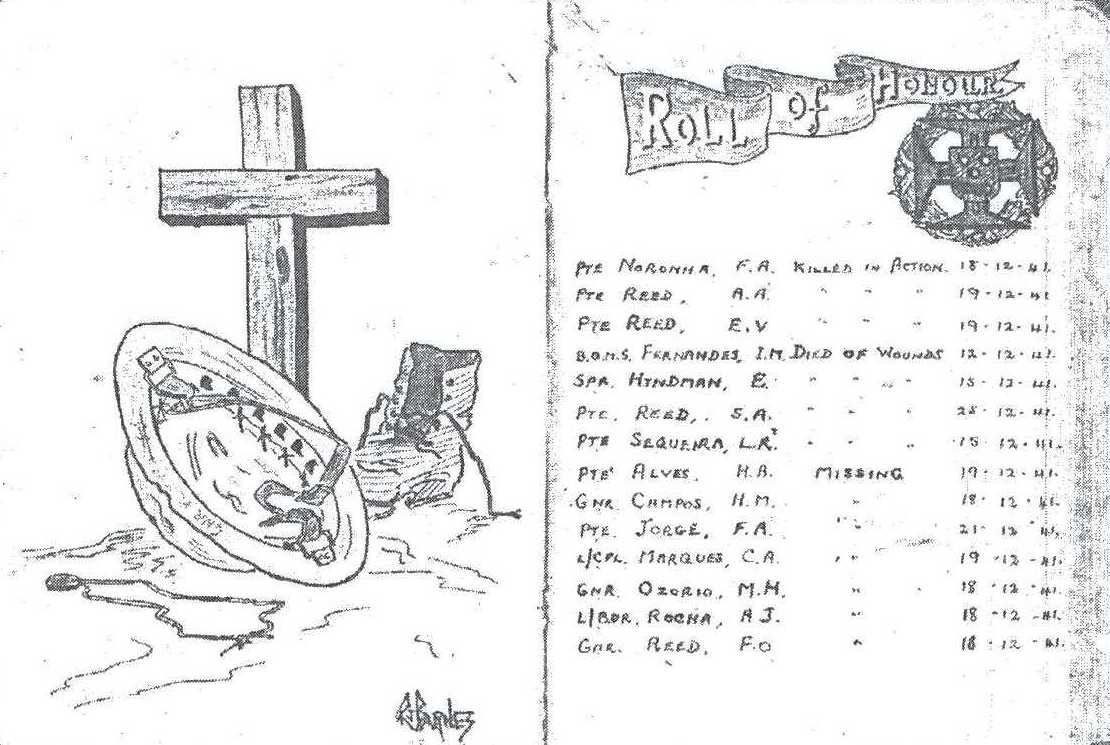

There were 12 greatgrandchildren of Estefan in the war in December 1941: 6 Noronha Brothers - Dick, Hermes, Riri, Gussy, Eddy, Francis, cousin Tony Noronha; Carlos and Joe Marques; Arthur Basto, Vicente Yvanovich Jr and myself. Francis Noronha and Carlos Marques were killed. Jr Yvanovich did not go into camp. Typical of the Volunteers, I did not know Jr was in until about 1980 when Eddy Noronha showed me a roll of names of No 6 Company which he had.

It may seem strange that there is no record of the Portuguese involved in the Volunteers in between founding and 1939. Not strange if you consider that the Volunteers were formed against external threats, whereas the Portuguese community being permanent residents, were more useful in the Auxiliary Constabulary. They were in such numbers that they had their own band (My father-in-law played in it).

The Hong Kong Volunteers December 1941

Numbers

| Corps HQ | 54 |

| Corps Artillery HQ | 5 |

| 1st Battery | 68 |

| 2nd Battery | 86 |

| 3rd Battery | 78 |

| 4th Battery | 67 |

| Field Company Engineers | 123 |

| Corps Signals | 40 |

| Armoured Car Platoon | 29 |

| No 1 Company | 104 |

| No 2 Company | 98 |

| No 3 Company | 114 |

| No 4 Company | 78 |

| No 5 Company | 99 |

| No 6 Company | 96 |

| No 7 Company | 41 |

| ASC Unit | 72 |

| Stanley Platoon | 29 |

| Pay Detachment | 17 |

| Fortress Signals | 17 |

| Hughes Group | 72 |

| Field Ambulance | 169 |

No. 6 Company (Portuguese)

Our No 6 Company was set up within the larger HK Volunteers as follows:

- Light anti-aircraft (i.e. Lewis guns) Captain HA de B Botelho commanded the company of 2 platoons.

- 1 Platoon Officer Commanding FVV (Chico) Ribeiro covered Hong Kong Island

- 1 Platoon Officer Commanding Eneas Cunha covered Kowloon

Training

The training was a bit haphazard! I worked in the Hong Kong Bank, Kowloon Office, where we had 8 Portuguese clerks, 4 of whom were in the same Company. The whole of 1941, we had field training one day a fortnight so in my office only two of us would go each time. We were doing light infantry training then, so one day, army instructors (a whole squad of 20 men) would demonstrate field tactics and the following fortnight we would show how well we learned. Problem was, we would be shown on the days I did not attend and invariably I would be picked to head the team to show how well we learned the lesson the next fortnight and nobody cottoned on!

I have no idea where or how the other units trained. I know the No 5 (Port.) Company - Machine gun - trained for 1 year on the Pill boxes at Wong Nei Chung Gap and in June 1941 they traded Post with No 4 (Eurasian) Company going over to the Western end of the Island near Mt Davis (luckily) away from the fighting.

Because we were to protect installations against dive bombings, we would be scattered in small sections in places like Aberdeen Dockyard, Taikoo Dockyard, Hong Kong Electric Power Station, Hong Kong Star Ferry Terminal (on top of Gibb Livingston), Kowloon Star Ferry (on the Kowloon Godown Building where we were), China Light Power Station etc. The absurdity of the set up was that we had never been at any of the locations or anywhere remotely like it!

Our Fighting

So here we went off to our war. We were paraded and then sent off into our individual sections. Packed into trucks and taken first to the armoury to receive our Lewis guns from storage and our live ammoammunition. I was put in charge of a squad of seven men. I remember I was 20 years and four months old, in charge of a squad. A Lance Corporal, with Marciano Silva L/CPL as No 2, Gino RemediosEugenio E? (1 year younger), Edo Silva , Damso Aquino and Henrique RibeiroHenrique Augusto Vieira Ribeiro #1045 or Henrique Augusto Vieira Ribeiro #1149? and one other. Our post was at Kowloon Godown, overlooking the Star Ferry Terminal. We each had a rifle, and we drew two Lewis guns from the armoury. These Lewis guns and their ammo pans came from Deep Storage and we had to spend more than an hour to get them working. The barrels were plugged with grease from end to end and we had to use boiling water obtained from the Godown to get rid of the grease. We also had to load the ammo pans with a mix of bullets and incendiaries. We only had six pans and these were the infantry pans which held 40 bullets, not the anti-aircraft pans which would hold 60.

We had 'coolies' to help us fill sandbags so we were soon operational. Then we waited for two days. Food was brought to us. A priest, Father Green, Army Chaplain, paid us a visit and gave us absolution and distributed communion.

Alarms during the evening of the first night saw one of our team throw a big funk, and I had to ring his father-in-law to come at night in the black¬out with his wife to calm him down.

On Thursday, 11 December 1941 the evacuation of Kowloon started. We on the roof of the Godown looked on as troops and civilians were evacuated to Hong Kong Island. Our orders were to stand fast to our post until sunset then we were to move to Holts Wharf, where we were to be picked up at night.

Meanwhile in the Godown, they threw open the doors and invited the populace to help themselves. Damso and Henrique went down and helped themselves to two kitbags full of cigarettes.

At sunset we packed up and made our way to Holts Wharf On the way Gino RemediosEugenio E? shot a looter brandishing a chopper. Arriving at Holts Wharf we made our way to the end of a wharf, to which was tied a Blue Funnel Steamer. The captain came down and asked us what we were hoping to do. We told him we were to be picked up that night. He told us he was going to bring his ship across to Taikoo after dark and we would be welcome to come along. I thought we might as well join him and off we went.

On arrival at Taikoo, we tied up at the sea wall and headed down one old gangway lying on the sea wall. This gangway had two handrails, was about one metre wide, but had a complete compliment of crosspieces, about one metre apart, but some of the floor boards were missing, so there were two or three places where you had to step on the crosspieces to get down. A misstep would mean drowning as we were carrying our guns (a rifle each, two machine guns and ammo). Fortunately, we did it safely and found to our pleasant surprise three sections of our Hong Kong Platoon emplaced in Taikoo. Gladly we met up with my cousins, Henry (Riri) Noronha, Francis (his brother who would die fighting the Japanese landing), Alex Azedo and others. We rang HQ at Club LusitanoThe Portuguese Club on Hong Kong Island and told them where we were and later that evening a truck came and took us to Lusitano. We spent the night at Lusitano and I met up with my father and mother who were billeted there.

The next afternoon we were trucked to Aberdeen, where we met up with Dick Alves (my future brother-in-law). Then we were again trucked off to the waterfront to the Lung Hai Hotel (eight stories high). We slept on the ground floor, hiked up eight floors to the roof to our post. We then got a call from Aberdeen to tell us Henrique Ribeiro had left his rifle behind! From the roof at night, we could see across to Kowloon Peninsula and we could see the night fighting of the RajputsThe 5th Batallion of the Indian Rajput Regiment fought in the Battle of Hong Kong. as they retreated to Lye Mun. They were successfully evacuated and one squad was stationed on our bit of waterfront and rested at night in the lane at the back of our hotel. I paid them a visit and found them rested but dying for a cigarette. So I went back and took a carton off Damso and gave it to them, refusing any payment (this would pay off in Prisoner of War Camp).

My squad was not very war-minded and I ended up on my own most days on the roof. Gino RemediosEugenio E? requested to swap with someone from another post, so he went to CAJ Ribeiro at the Fire Brigade tower and Joe Luz came to us. We were given individual leave to go to Lusitano or visit family in billets. On Christmas Day Joe Luz went to visit his family at Canossa Convent. My father had given me a bar of chocolate earlier so I gave it to Joe to bring to his daughter.

By the time he came back we had the news that Hong Kong had surrendered. We were told to go to Murray Barracks, so we threw our rifle bolts and the lynch pins from the Lewis guns into the sea and marched off to Murray Barracks. I had no winter gear, but when we arrived in Murray Barracks, I managed to find a thick pair of khaki pants and a discarded overcoat with no buttons except a clasp at the top. The coat must have been from a tall man as it reached to the ground. It worked well as a blanket.

During the period we were in the hotel, the telephone was connected. In the evening I would telephone Paula Hollands, a good friend of the family. The family lived in Happy Valley, surrounded behind Japanese lines, and I could cheer them up. I could not ring Lusitano, except for official business.

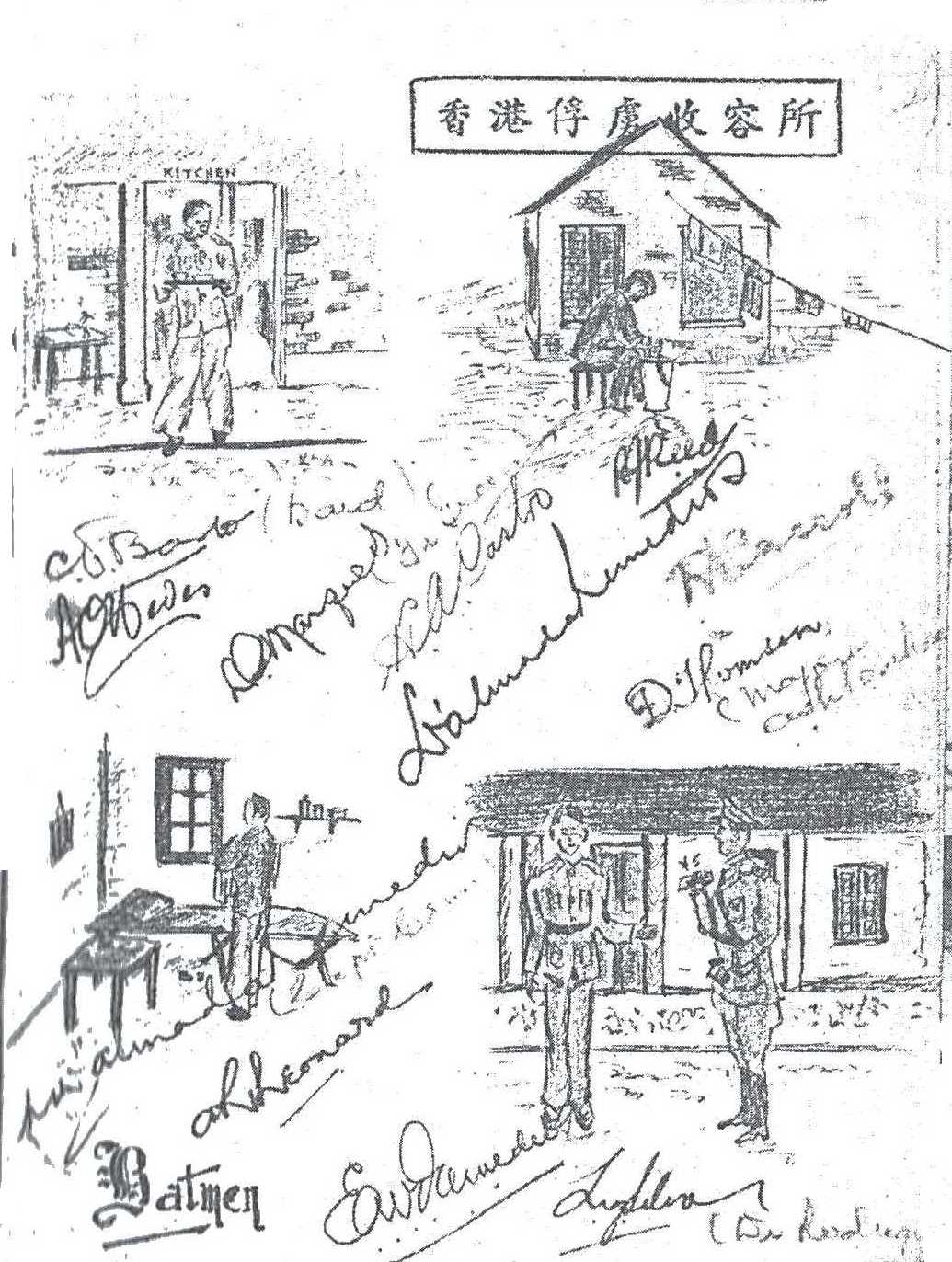

Into Prisoner-of- War Camp

After five days at Murray Barracks we were marched down to the Ferry, then shipped to Kowloon and marched to Sham Shui POWprisoner-of-war Camp. On reaching the camp we were allocated lines of huts, about 50 men to a hut. All the huts had been looted by the Chinese including the windows, frames and all. There were some mat sheds at one end and some enterprising souls started stripping the palm fronds and so we had something to block the windows. I had paired off with Eddy Noronha and had somehow acquired a blanket. At night we slept on two iron bed frames and some palm fronds, one blanket under us and one over us, with our great coats over each. After about a week we were shifted to a new line of huts (we, the Volunteers). We had to leave our huts intact, including beds and no windows. After settling in and stopping the windows in the set of huts, we were told we were to move again. This time we would not accept orders to leave the works behind and we proceeded to dismantle the window shades, which now included some corrugated iron sheets. I well remember the sight of Brigadier Peffers arguing with Lt Chico Ribeiro, saying 'you were ordered to leave these Lines (huts) intact. Tell your men to stop at once!' and Chico shaking an iron bed leg at the Brigadier, telling him to get lost!

Eating arrangements were very haphazard at first. We were given some empty gasoline drums as cooking utensils for rice. The first few meals were disastrous; then the Volunteers took over, we had someone who had been a ship's cook (Keeble) and a few other useful types, so things became a bit better.

The Indian troops — Rajputs & Punjabis and some Indian Mountain Battery units — were kept separate from the rest of us. They were better prepared than us, better disciplined and they had carried a lot of their food into camp and the Japanese were anxious to get them to fight against the Allies. The Indian squad leader managed to find me and instructed me to go to a certain corner of the camp once a week. I did so at night and was rewarded with an Indian army biscuit each time from the squad's rations. Wonderful thanks for some cigarettes which were not mineSee the previous section "Our Fighting". These biscuits were about four inches square and one inch thick, and very nutritious. Unfortunately, the Indian troops were soon moved away.

Meanwhile the camp was very much in a state of confusion! Nobody was in charge of anything. The state of the toilet blocks became a complete mess. The lavatories of the camp were old fashioned squat down and unload into trays two feet long, nine inches high and nine inches wide. In peace time, soil collectors came every night to take away the soil for the farmers to use on their fields. Once the war started, the collections stopped and after two months of overcrowding the mess could be imagined. The Volunteers took charge of the situation. RSM Jones organised working parties. I remember there was an Indian Army mule cart with high iron wheels, a high tray and a solid tongue in front. Two men in front to pull like mules and two more behind to help push and unload. We moved all the trays, took them across the parade ground on the cart and washed them out in the sea. In the meantime, others were washing out the latrines. RSM Jones established permanent fatigue parties to help around the camp.

This clean up of the lavatories was not without humour. The fussier ones, instead of grasping the handles of the trays by hand, used hooks scrounged from scrap. These trays were old and rusted and overloaded. They had to be tackled by two men each, and had to be lifted head high to be loaded onto the cart. I remember one chap getting drenched with the lot from a tray when his hook broke through the rusted handle. He took about 10 showers to clean himself.

The Japanese would come in and take 40 men out to do work. I remember going out on one of these trips to clear a road to the New Territories. Loaded on to two open trucks, you had to hang onto the next man as there was only a low sideboard and the Jap driver drove like a madman, cornering at speed.

Around February 1942, people started coming to the camp bringing parcels. Some days it was easy, some days difficult. About this time, Tony ReisAM Reis, Lew (Rios) Remedios and Damso Aquino and one other slipped out of camp. This parcel exchange went on until August, when three men escaped. It had settled to a weekly affair but was finally stopped on the first week of August 1942 after three prisoners, John Pearce, David Bosanquet and Doug Clague escaped. Why I remember: I turned 21 on the 12th of August, Jerry Gosano on the 8th. He got his birthday parcel, I never got mine. My 21st birthday dinner was half a bowl of rice and clear vegetable soup, with three small scraps of vegetables floating in it. We were being punished for letting those prisoners escape! I remember standing in the parade ground, under very heavy rain, rain that turned the parade ground to mud, so that I lost one clog which sank into the mud, a good six inches deep! We were there 2 or 3 hours.

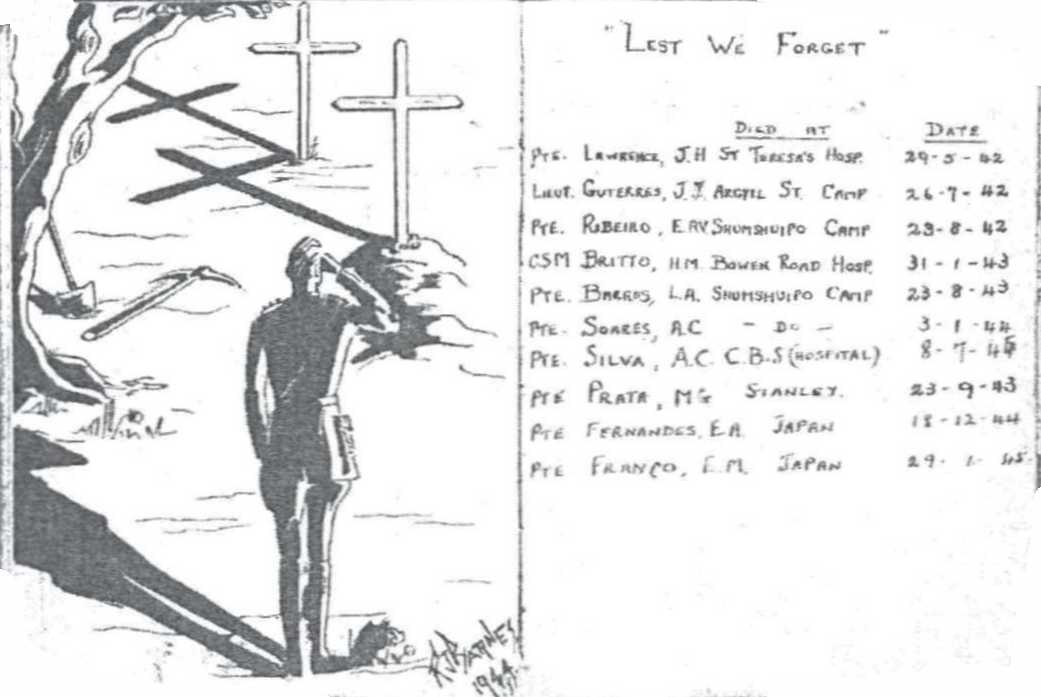

About this time there was a lot of diarrhoea, caused by a lot of prisoners filling their stomachs with water. Then came an epidemic of diphtheria which saw a lot of deaths. At first, when a man died the camp trumpeter Charlie Bellchambers would blow the Last Post, but they stopped when it got to five times a day. Shortly after they stopped, the record was set at 11 deaths in one day. By this time most of the officers had been transferred to Argyle Street, where there was a small refugee camp near Kai Tak, except for the Canadian officers who refused to be separated from their men. We buried our dead on the hillside below the Central British School, within sight of the camp.

Until April 1942, we did not have a priest in camp. The Portuguese Co's 5 & 6 were in two huts side by side, and we would gather on Sundays in one and say the Rosary together. Father Green was the Army Catholic Chaplain. Being an Irishman, he was considered a neutral, but he went to the Japs and volunteered to go into camp with us. At about this time the Pope sent about HK$40,000 to purchase comfort for the Hong Kong POWs. Father Green asked to see Colonel Tokunaga and demanded to know what had been done with this money. He was severely beaten up, and suffered from the beating for the rest of his stay. I remember him once stopping a Mass halfway through because he had dirtied his pants.

Father Green, on coming into camp, called me up and asked me to be choirmaster. He asked me my name and I replied "Philip" and he said "Oh no, you're not Philip, you're too full of the old Mick. You should be Micky" and he called me Micky the rest of my time in camp.

Also in this period, the North Point Crowd were taken into camp, so the Noronha boys were reunited. Six Noronha brothers went to war, one died. The Reed Brothers were not so fortunate: six brothers went to war, four died. Memie Gonsalves, Turibio Cruz and Bobby Barnes were in this lot, coming into camp.

Life in the Camp

Many have asked why we were not as badly treated as those in Singapore, Malaysia and Borneo. I think the reason was, the Jap fighting soldiers, after taking Hong Kong, were moved forward to the front line. We only had them on the first few months, then we had some Koreans (who were also tough). Then for more than half the camp period we had Taiwanese, and as the war went badly for the Japs, the Taiwanese became more friendly and cooperated in the Black Market. I remember in the beginning, the Japs delighted in coming into the camp, smoking a cigarette and laughing at the sight of British soldiers scrambling among themselves to get the thrown butt.

One of the consuming passions in camp was Contract Bridge. There were individual tournaments and team matches. I remember this lot in one hut: the huts were poorly lit by weak bulbs, with tins pierced with small holes as lamp shades. Lights would come on at 6am and directly under this light would be four players, cards dealt, just waiting for the light to see their cards. There were groups who played regularly for money, with accounts to be settled after the war (and they were).

We had another amusement: we were plagued with flies, what with dead bodies, unsanitary toilets, etc., so the Japs promised to pay one pack of cigarettes for 100 dead flies. This gave rise to disputes and even fights: imagine someone swatting at a fly and half killing it and someone else killing it. Whose fly is it?

After a couple of weeks of success, the Japs reduced the reward to five cigarettes per 100 flies, some smart chaps would cut a fly in two to increase their kill. Some smokers were so desperate, they would trade food for a cigarette. One cigarette was worth 10 Yen or one duck egg. You could get cigarettes as part of your pay if you worked. Non-smokers like Memie and me were well off.

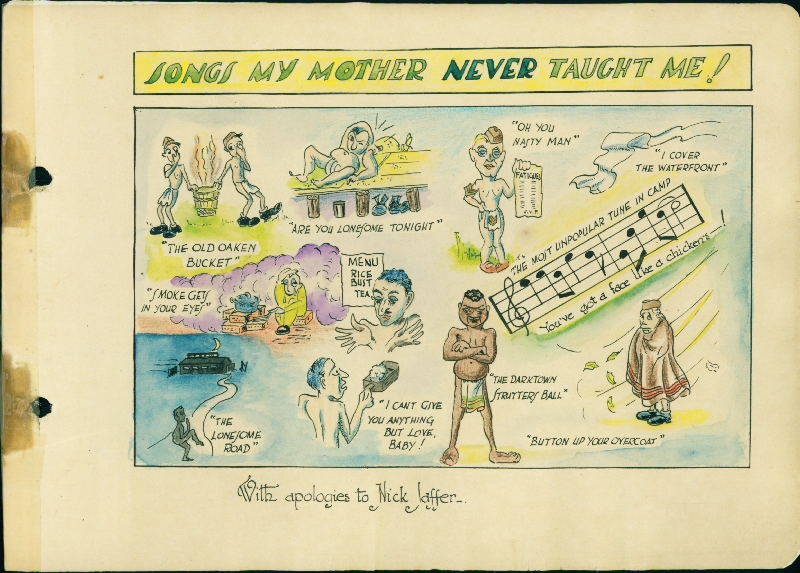

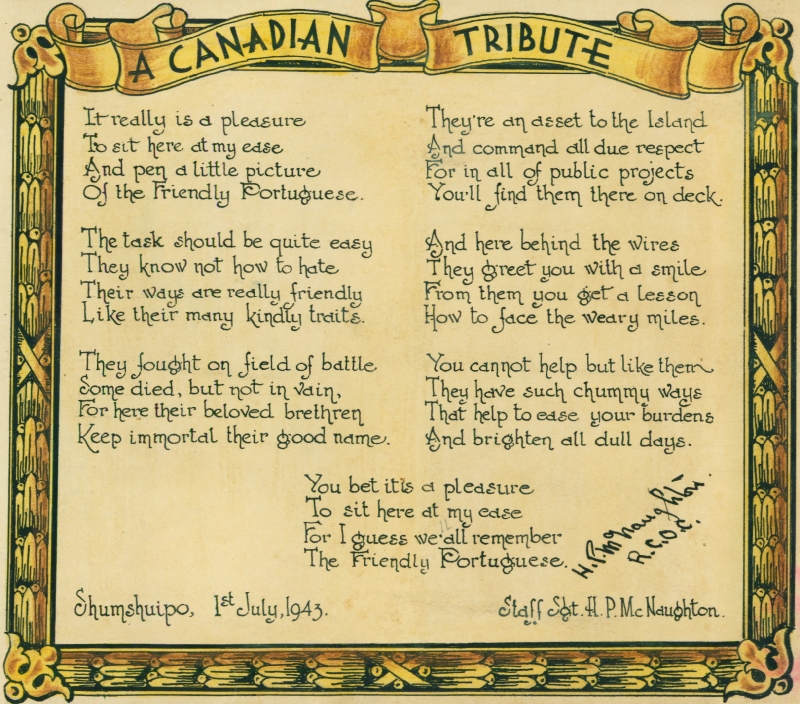

The officers were paid so they donated part for a 'comfort fund' for us lowly ones. We had a band, Canadians and British and about once a month we would have a concert on the parade ground and any one could go up and sing and/ or recite and get a cigarette. Some bloody awful acts came on for the cigarette.

Meanwhile, the first draft of men had been sent to Japan, and there was noticeably more space. Just before Christmas 1942, one of the Canadians dressed up as a girl and made a tour of the camp. I remember I was relieving myself at a storm drain and opposite me was Itensen, a Russian Jew, also relieving himself. This Canadian approached us and said "Naughty, Naughty!" and ltensen stuffed his penis in and peed in his pants. By this time in camp the Canadians had become very friendly with the Portuguese boys. Afterall, shortly after they arrived in Hong Kong, they had played softball against Club Recreio and many of the players were there in camp. The Canadians put on a show in their lines and invited several of us to the show. In this group was Nanelli Baptista, Tony Alves and myself. Talking among us later, we thought we could do better. We decided to do a Variety show. The Japs had allowed musical instruments from families, Ely Alves got his violin. We made a small stage by putting four iron beds together and covered it with blankets.

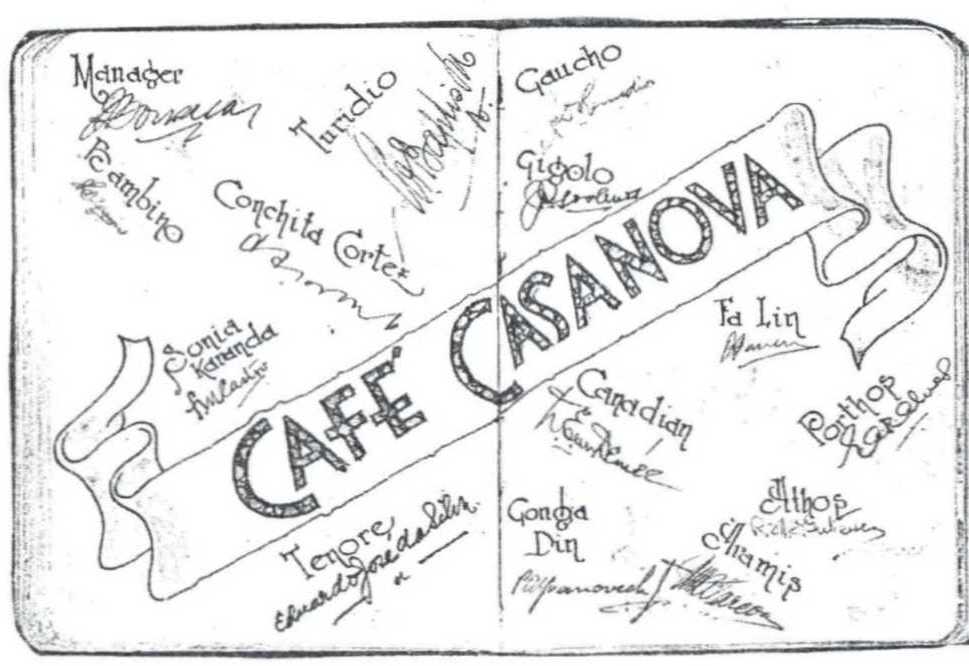

I was involved in putting on a risqué skit involving David DemeePrivate David EM Demee as a Canadian soldier trying to contact a Chinese Girl, Fa Lin, Xaviers and me, as an Indian Watchman as go between. I also took part in a musical number. We put on the show for our boys and invited some of our Canadian friends, including the camp Doctors, Blaver, Le Boutillier and Corrigan (Canadians). These Doctors were left behind when the officers were moved to Argyle Street. The show was so successful we were Told to do a show for the camp. So was born Cafe Casa Nova.

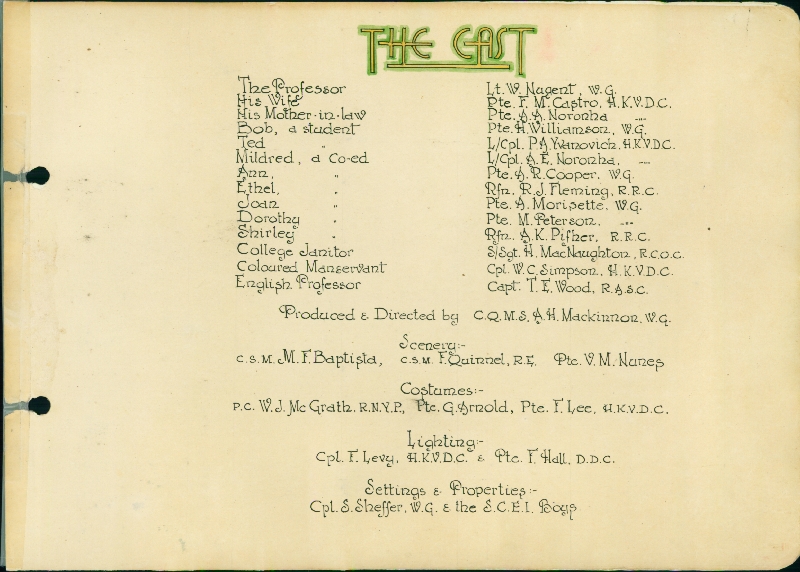

Cafe Casa Nova

| Manager & M.C. | Johnny Fonseca |

| Gigolo (serenading lady) | Zinho Gosano |

| Lady & Singer (Sonia Karanda) | Sonny Castro |

| Skit | |

|---|---|

| Bambino | Ino AquinoPossibly José Maria Pompeia Loureiro Goulart de Aquino #3126? |

| Grandpa Turido Gaucho | Nanelli Baptista |

| Doing a tango | Jimmy Remedios |

| with dancer | Gussy Noronha |

| Tenore | Edo Silva (Sang Maparri) |

| Violin Trio | |

| Porthos | Ely Alves |

| Athos | Reinaldo Gutierrez |

| Aramis | Ala AlaconPrivate Mario Francisco Alarcon |

| Skit | |

|---|---|

| Canadian Soldier | Davie DemeePrivate David EM Demee |

| Fa Lin (Chinese Girl) | A Xavier |

| Indian Watchman (Go between) | P Yvanovich |

|

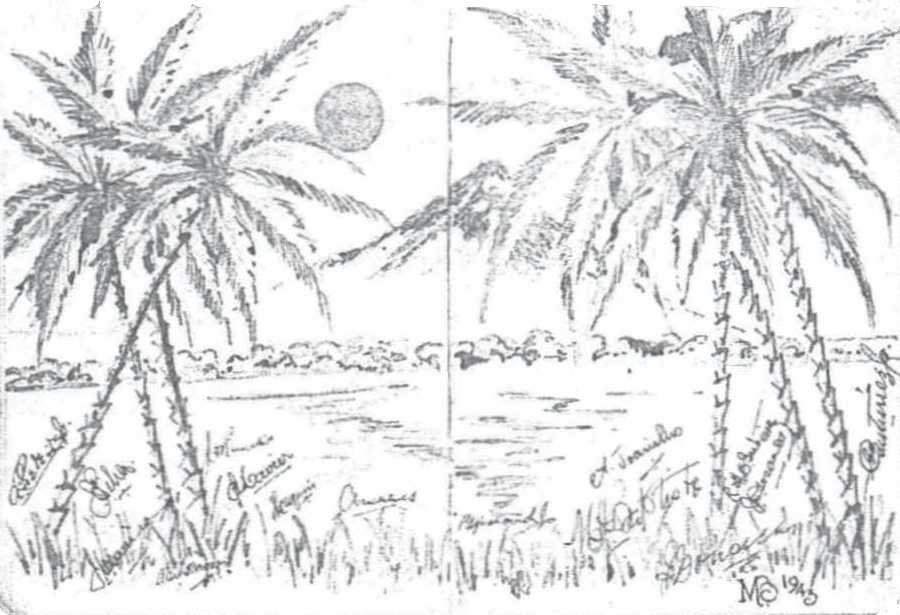

The second act: A Hawaiian scene

Some of the participants

Girls

|

Tony Alves

A JuanilhoPrivate Augusto Juanilho

|

| Singers | |

| Band (string) including mandolins & guitars |

Johnny Fonseca

C (Grey) GutierrezPrivate Charles L Gutierrez, possibly Carlos Gutierrez #25063

D FuertesPrivate Domingo Pascual Fuertes

and about 20 more in all

|

This string band was very popular and gave several recitals. They played from memory as they had no music. The scenes were designed and painted by Nanelli.

By this time, I was working in the Royal Engineers (RE) yard, as an assistant to a carpenter, Staff Sergeant Frank Quinnell. By consenting to expand the show and do it for the camp as a whole, we needed a bigger venue. The RE yard was called in and we all decided to use the Big Hall. To build a stage, we used as a base two billiard tables from the ex-Sergeant's Mess. Planks from a shed, sacking strung across to make a stage curtain and for the back drop we used straw mats sewn together. Nanelli Baptista painted palm trees on this straw backdrop using charcoal and white lime. It was so effective, some professional artist asked Nanelli "what size squares did he use"!' He did it all free hand (with the help of cigarettes, the officers had to keep him in cigarettes!).

The show was in two acts. The first was a cafe scene in which we had Sonny Castro dressed as a girl imitating Carmen Miranda. Also playing a girl was Gussy Noronha doing a tango with Jimmy Remedios, with Zinho Gosano singing, serenading Sonny, and with me doing our skit with David DemeePrivate David EM Demee and 'Fa Lin' Xavier, Ely Alves doing a violin solo and another couple of acts. Edo Silva sang an operatic solo, 'Ma Parri' from 'Martha'. The second part was a Hawaiian scene.

It was all well received. I remember one cold night I sang a solo 'Lonely Road' and had to whiten my hair with rice flour. I spent two hours after the show washing my hair with very cold water to get the rice out. We had jazz concerts, with Tony Alves and myself singing solos, Canadian Sweeney on clarinet, Coriggan on saxophone, Ely Alves on violin and Reggie Xavier on guitar. We would have jazz sessions in a hut where the Labrum brothers, Vic and George, slept. These two brothers had the most complete store of jokes. They could go on for hours without repeating. These jazz sessions were played in the dark (back to the early days). The concerts on the parade ground had the band in the middle on a raised platform and the audience in front. So, when the Americans raided and blew up Lai Chi Kok Oil Farm, we would sit and look at the stage and the burning going on behind, and cheer when an explosion occurred! Like we were cheering the band.

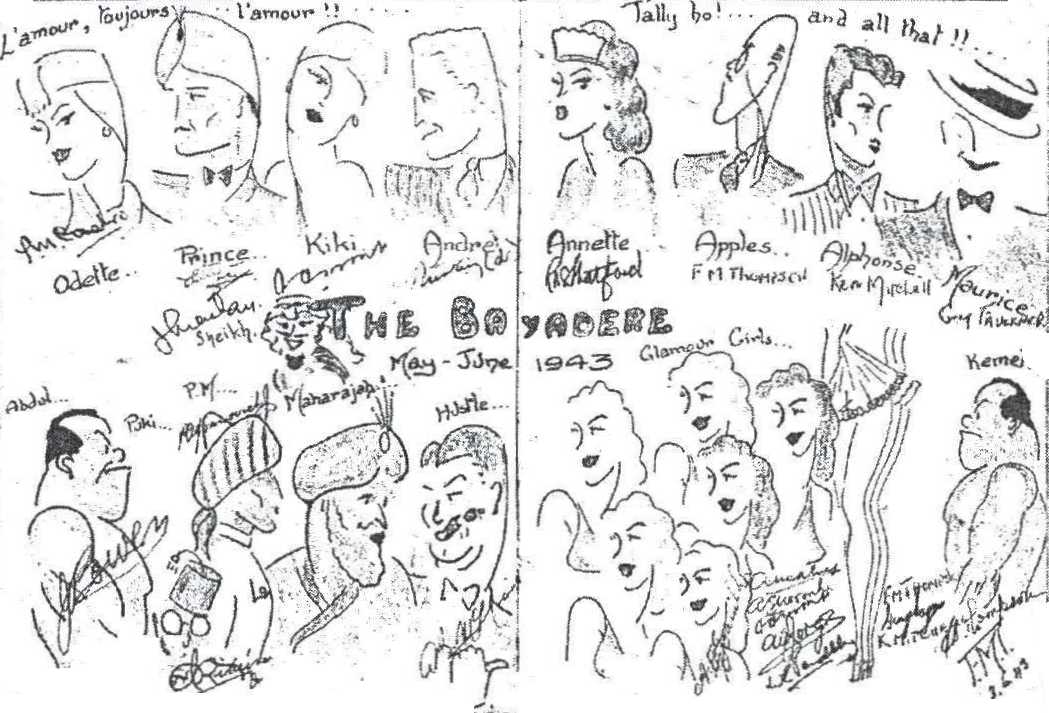

Prime Minister of Maharaja Court

One of the shows we did was a mixed effort. The director was a Jewish Russian volunteer, Sonny Castro the leading lady (Slave), Zinho Gosano was the hero (Prince), Gussy Noronha (gold digger), several volunteers as hangers on, Joe Bowen and Charlie Thomson as slave guards, myself as Prime Minister of the Maharaja court, slave girls, Tony Alves, Eddy Noronha, Gussy Noronha (two parts), Achilles Jorge and one Englishman, Padbury, and the Maharaja, the principal, a Canadian. On the second performance (of three) I caught the imagination of the audience for 5 or 7 minutes. I had the whole hall laughing nonstop, without saying a word, just with face and body language. The audience had all eaten garlic and the waves of laughter were heavy with the smell. I finally had to calm the audience down so we could go on with the show. The Maharaja, one of the principals, was so upset by my impromptu performance declared himself sick the next day, so we had to cancel the third show. Mine was a bit part, and I stopped the show!

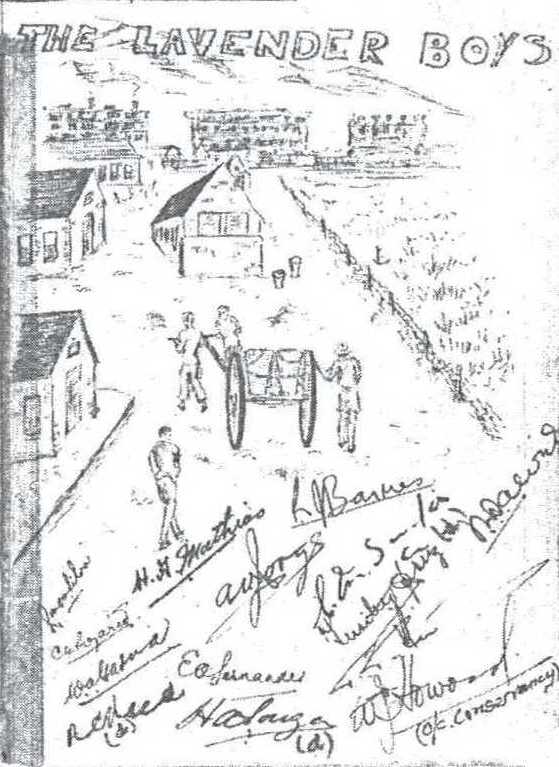

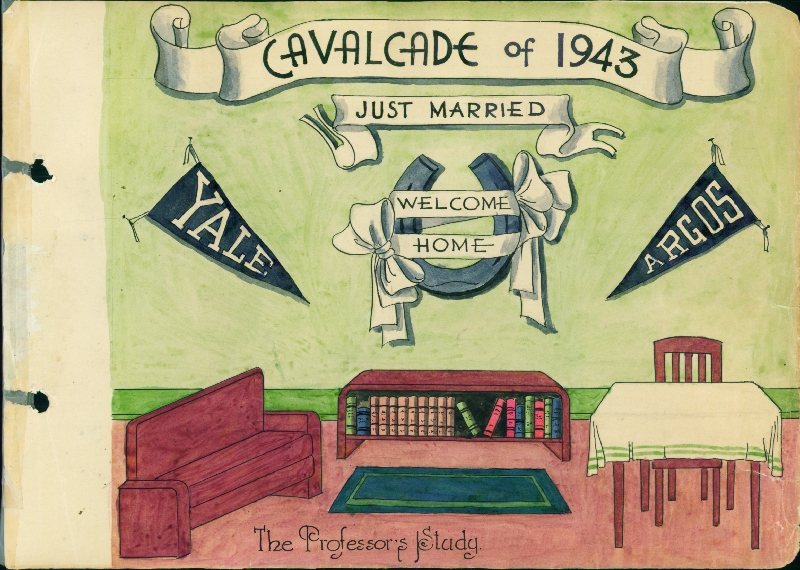

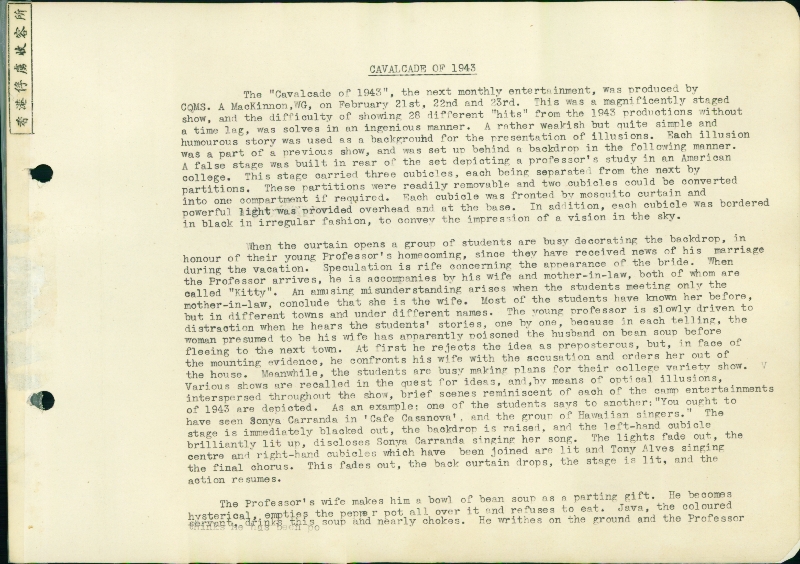

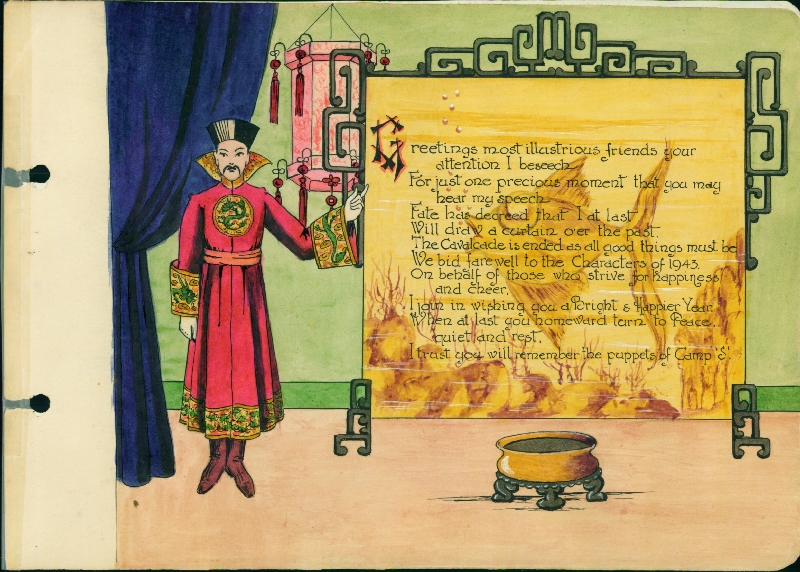

Cavalcade

Shortly after this, we lost a few more actors. Gosano, Faulkner, half the string band and so forth were all sent to Japan. So someone had the idea of doing a Cavalcade. The basic plot was that there were four people around a coffee table at a café with a waiter or two, reminiscing about the previous shows: "Remember when ..." The lights would go down and scenes from the previous shows would appear at the back. This show was a triumph for the back-room boys. I was lucky enough to be on both sides.

As helper to Frank Quinnel the carpenter, I helped design and build a small stage at the back, four feet high, divided into two sections, 2/3 and 1/3, by a demountable partition. We were given two big pieces of mosquito netting, but neither piece was big enough to cover the whole stage, so we had to work out some way of joining them together without making the joint visible; this we did by a diagonal joint.

The electricians, Lionel Rodrigues and Felix Levy, had to install lighting at the back and devise a way to fade the lights in front and bring up the backlighting. They did this by using a porcelain drain pipe, sealed with concrete at the bottom; they filled it with water and dipped a home-made water heater in. The final scene was so long, the water in the pipe would almost boil away before they could remove the heater. The mosquito netting made the back scenes seem slightly hazy and the audience was left amazed at the result.

I had about four changes of costumes and in between I was out to see and admire what we achieved. Poor Sonny Castro was in practically every episode, so he only grasped one chance to see some in between costume changes!

There were some shows after this, mostly plays. Meanwhile, each time a draft of prisoners was sent to Japan we would put on a farewell concert for them. The mainstay would be the jazz band, Ely Alves, Corrigan, Sweeney, Xavier, the "girls" Sonny C, Tony A, Eddy N, Bob P, principal singers, me & Tony Alves.

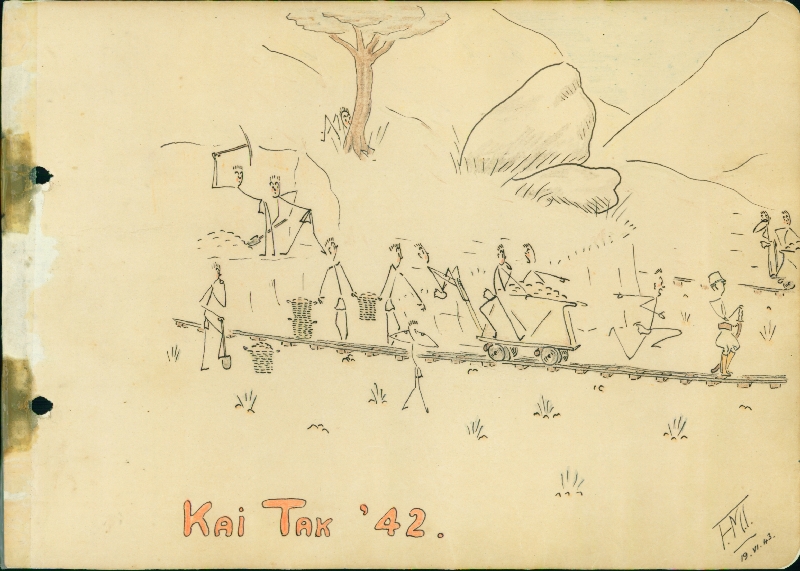

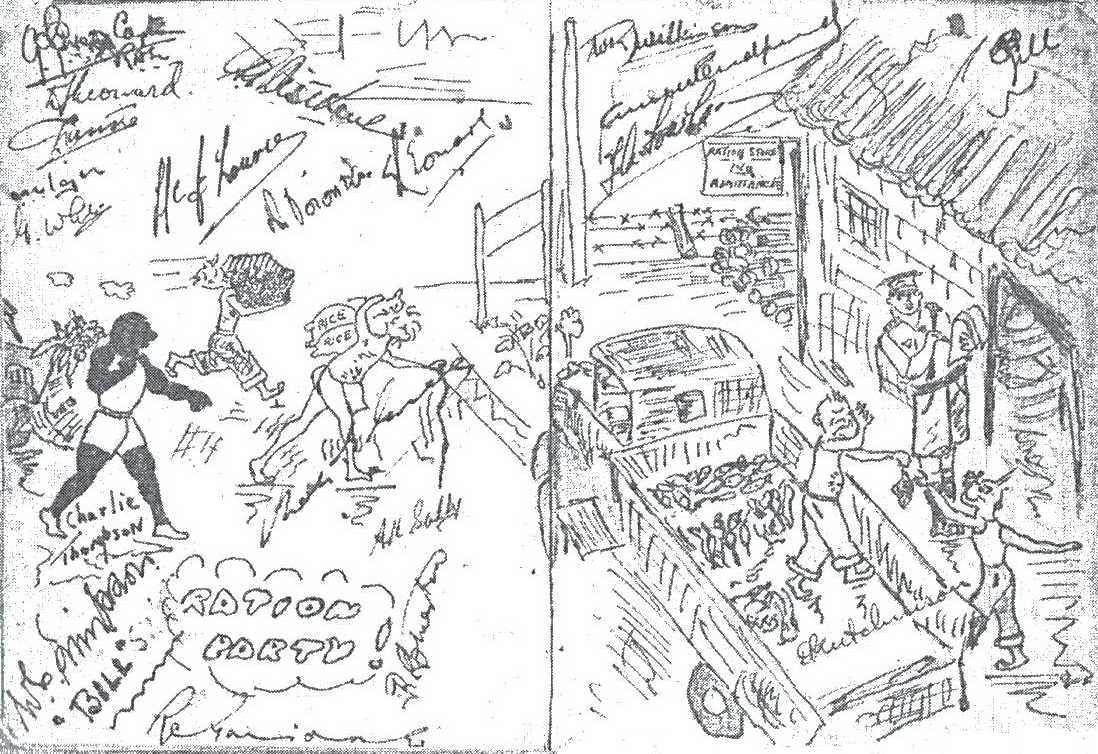

Work Parties

The Japanese started regular work parties to Kai Tak to enlarge the airport. With pick and shovel and rail carts we would attack the hillside. The work party would fall in at 6am and board a flat-topped barge which would be towed across to a jetty near Kai Tak and we would be marched under guard to our work. There was a stretch of 200 metres where we were near the public, within 30 metres. At the start of this work party I had injured my knee and could not go. My cousins travelled together in a group, so it was very noticeable that I was not there. After about two weeks I was well enough to go. There were the Noronhas, Joe Marques, myself, Arthur Basto, my brother-in-law Edo Silva . On the roadside were my sister Lolita (Lo) and an old small lady. It was my mother; in six months she must have lost 40 pounds and six inches in height. I had to warn my cousins not to show their shock.

Work at Kai Tak was hard. We used pick and shovel to load carts on light rail with earth and rocks, which was run to the sea wall and dumped to reclaim the land. The rails were rickety and because of the slope 2 chaps would ride the carts and use a piece of wood as a brake to control the speed. I got a big splinter in my palm from the handling of the cart, which festered for a month before I finally got it out.

Hard Work

From time to time, batches of prisoners were sent to Japan. The depletion of the workforce meant those left behind had to work harder. A lot of the remainder were unfit so the fit pool had longer stretches, often eight days out and one day of rest (to do your washing, etc.). I remember on one of my rest days there was a call for 30 men to go to Aberdeen to work the gasoline drums; 20 of these were unfit, so it was very hard work for us fit men. I arranged to rotate the fit workers and we survived the day. The work entailed rolling the oil drums (400lbs) out from the forest shelter to the concrete path leading at a slope to the loading area for the trucks, unloading the trucks at the jetty and loading them onto a barge or motorized junk. Loading the trucks involved standing one drum on end, resting the tail gate of the truck on the edge of the drum, then lifting the individual drums on to the standing drum and pushing it up on to the truck bed. Two men on the truck then had to stand the drums upright and move and pack them in. Two men at the pier had to unload the truck, roll them down the pier and stand them upright ready to load on to the boat. Very hard work for 10 fit men, a killing day.

Tunnelling

Another of the jobs we had to do was digging tunnels in the hillside as ammo dumps. I was only involved in the one tunnel in Ho Man Tin (my home suburb) into a hillside behind Dr Alex Basto's house. It was not a very stable hillside as most of it was the fill from the Diocesan Boys School above. The entrance to this tunnel had the first five or ten yards roughly propped. Then no more props as you went in. Because it was not very stable ground the tunnel was undulating. I remember a big hump where a lump from the roof had fallen in. The tunnel twisted in and out a bit and the end where we worked with pick and shovel was 50 metres in and widened into a big room. We had one sentry per tunnel and he would not venture in at all. We had no ventilation; lighting was from an oil lamp, open, with a wick. Because of the lack of air the flame would be six or eight inches high. We would travel to the site from camp, dressed in shorts, singlets and shirts. On arrival, we would walk in to the end of the tunnel, remove our shorts and shirts, and work in singlets and fundoshis (loincloths). We (at least my lot) did not actually do much digging. The sentry stayed outside, we sat inside and chatted, scraping the shovels down the walls and thumping the picks on the ground (but not too hard or the ceiling might come down) so the sentry could hear us. Because of the lack of fresh air we sweated heavily and the lamp smoked a lot, so we ended each day black around the mouth and nose. Because you were eight days at a stretch, when you returned to camp you had a shower and put on a clean singlet. But the next morning you took off your clean singlet and fundoshis and put your dirty clothes on again. No one had clean clothes. I really felt murderous then (late 1944) each time I put on the dirty clothes.

By the way, the tunnel we dug for the ]aps was filled with ammo. About one year after the war ended, the tunnel blew up in the middle of the night and strewed mud over a distance of 500 metres. Our house, about 250m from the site, had six inches of mud on our flat roof The police reasoned that it was caused by Chinese fishermen trying to steal explosives to use in fishing. We had had plenty of rain so the ammo in the tunnel was quite damp and started to let out fumes. An open flame would have caused an explosion.

The labour situation in Camp

Officers

Each Officer had a batman. They did no work; their batman looked after them, made their beds, drew and served their meals, washed their clothes, etc.

Professional staff (Tradesmen??)

Carpenters, tinsmiths, bricklayers, etc., worked in camp. Some had assistants but they did not go out on work parties. The official rank for majority was Staff Sergeant.

Permanent Work Parties

The cooks, wood choppers, ration party, conservancy party (who cleaned the toilets every day) and the office staff worked in camp and did not go out on work parties. My brother-in-law Tony Alves worked in the camp office.

The camp ration party only went out to draw rations, occasionally calling on extra help to move heavy stuff, like 200lb sacks of rice.

Being a member of a permanent work party did not exempt you from being drafted off to Japan. The cooks, wood choppers and the ration party all were drafted off and new bodies installed.

Semi-permanent job

There were semi-permanent jobs, like mine. About this time, I got a job as a carpenter's assistant and worked every day in the Royal Engineers' yard. This was a quadrangle of buildings around a tennis court. The carpenters had a room, the metal worker (assistant Reggie Xavier), the book binders (Labrum brothers) had a room . I used to sing a lot, all the old ballads and requests would be called out.

When necessary I was put to work digging, shifting earth, flattening sheets of corrugated iron, putting up and taking down barbed wire (my Russian friend called it "barbary wire") and was still available for outside work.

I was also in charge of a work party, myself, Ely Alves, Lionel Silva and Delano Lopes. We would have to move rubble, earth for mortar etc, using the Indian mule cart. When working, it was usually Lionel Silva and I up front holding the crossbar chest high, and Ely and Delano pushing at the back. Fairly hard work pulling through sand and mud, we would go along talking, and Delano would irritate us because he could not talk and push at the same time! The cart would swing out of line and we would yell at Delano.

Unwell workers

The unwell workers did light work. They were, in effect, the walking wounded with heart conditions, the elderly or unfit. When I was recovering from malaria (weight 75/80lbs 34-36kg) I had such a job, gradually progressing to something harder until I was fit again.

We were in Jubilee Buildings at this time, and I remember it being summer we would sit out on the verandah to have our evening meal. For a period, due to the tides, a corpse would come floating by at meal time. Bit of excitement. In the flat occupied by Alex Azedo and others, the former occupant had built a storage space inside the entrance lobby to store suitcases, etc. While we were occupying the building some engineers had worked up a radio and they used to come at night and use this space. One night two sentries paid a surprise visit and stood directly below this space to check the flat, never suspecting what was there!

Camp Characters

We had a few drafts of POWs for Japan and we would have a special concert for them. The favourite "girls" were Sonny Castro, Eddy Noronha, Tony Alves and Robert (RL) Pereira. The band was usually Ely Alves on violin, Corrigan on saxophone, Sweeny on clarinet and Reggie Xavier on guitar. Another result of the drafts was that actors, such as Zinho Gosano and Guy Faulkner went off to Japan. The drafts chose men at random. I remember the last one took Tony Noronha, Riri Dicky Noronha (both married) and left behind Ermie, Eddy and Gussy, three unmarried brothers. Ermie tried to replace Dicky. All the Noronha boys survived.

We had some odd characters in camp, and some who went quietly mad. My boss in the bank thought all places of common use were full of bugs. He would use his elbows to open taps resulting in both elbows going septic. Every evening he would go down to the parade ground where he could look across to the Hong Kong Bank and bow to the bank.

Some were obsessed with cleanliness, others were unclean. One of our unclean ones was notorious. On one occasion he went to see the doctor. The doctor refused to examine him without him first having a bath, so Nanelli Baptista detailed five strong chaps to take him for a shower. They made him strip and go into a shower cubicle. They stood outside listening to splashing for five minutes; when they looked they saw him standing in a corner and splashing the water about with one hand. They took him out and stretched him over the basins and scrubbed him down with a scrubbing brush.

Another time he was sitting talking with his brother-in-law, who drew his attention to what looked like a scab on the back of his hand. Asked what it was, he said he must have scratched and drawn blood. Then the scab started to move. It was a louse!

One chap read that one should chew each mouthful 20 times. He then did so, chewing each mouthful of rice 20 times. One collected recipes from the newspapers the Japs had sent in for toilet paper. At each meal of rice he would have a different recipe in front of him, to flavour the rice.

Some became depressed. I was told by Father Green to look after the first one, a classmate of mine, then later two married men, older than myself. One such was Benjy who was shy of washing. He was put under charge of Bob Sheehan, a big Ulsterman, a heavyweight champion boxer. It was summer and Bob would shower 2-3 times a day. Poor Benjy would plead with Bob, 'Mr Sheehan, we'd had a shower earlier, remember you called me when we were doing this or that'. Bob would deliver a thump on his head or shoulders and yank him on the way.

Whilst I was in the hospital with malaria, I saw one of my friends die. He went out of his mind, refused to eat the diet of rice (badly cooked) and vegetables, and insisted on being given eggs and bacon for breakfast and steak for dinner. Another death was a ship captain. He came into camp with a suitcase of whisky and drank himself to death. He would refuse the food, saying he had eaten a steak or some such at the Gripps or some other restaurant.

I was becoming an expert on scrounging and stealing from the Japs. Once while working in the Jap storeroom where they had some pickled turnips stored, I managed to pinch three eight-inch-long turnips from under the noses of two sentries watching three of us. Another time I stole three mugs of oil from the sump in the oil store. All this dressed in a fundoshi and a cap. (The cap was used to carry in the tools — hammers, cold chisels.)

My good friend Memie and I messed together and shared our goods. We both worked and earned and we made a pact to lend to anyone who needed money or goods and not insist on repayment. It was no big deal, just 10 or 20 yen to buy something special — for example, when I stole three mugs full of peanut oil, anyone who needed a spoonful could come to us. Some tried to take advantage of our generosity, but we were never out of oil or money.

On one of the working parties, we were each given four Marie biscuits for lunch. Dr Rodrigues came to the Portuguese huts and appealed to us to try and bring back as many biscuits as possible for Father Green who, because of the beating he got, could not stomach the rice and vegetable diet. So we tried. RSM Jones tried to send as many of us as possible, but it was a popular job because of the biscuits, and if you were the only Portuguese on the job trying to bring back two was hard, considering one often had to pause and rest, dizzy from hunger. Father Green survived and went back to England, retired and became the mayor of a small town.

The RSM of the volunteers had only been in Hong Kong for about a year. He had a strong dislike of the Portuguese companies, saying we were not well disciplined. Then in camp, about mid- to late 1942, he discovered we were a happy lot, and moved his bed into our midst because the rest of the volunteers were down in the mouth and miserable. He became good friends with many of us. After the war he came several times to the Alves' house for dinner.

Note on Malaria Attacks

The camp very early on ran out of Quinine pills. Each time you had an attack you got one tablet. Going in to hospital with an attack meant you brought over your blankets and clothes, and occupied an empty bed in a ward of maybe 30-40 beds. In the first three days your fever ramps up and you shiver (my temperature would go over 40° C and I would hallucinate). Then the fever breaks and you wait. They check and if you have had no fever for two to three days you are sent back to your hut, carrying your blankets and clothes, then you wash your clothes and air your blankets and a couple of days later the fever strikes again. I personally found that for me to get the best out of that one pill, I would go to the bathhouse and make myself vomit my evening meal before taking it.

I had contracted Cerebral Malaria six months before the war started, from a week's compulsory camp. The doctor said this type never goes away.

In March 1943, I had a bout of malaria, fever over 104°F (40°C) and was put into the camp hospital. Funny, I would hallucinate when the fever went over 104°F, seeing the same vision every time. My father managed to send in a small tin containing 12 Quinine tablets. I only needed two as there were some in the hospital stores and retained 10.

Then early in 1944 the camp ran out of quinine. Ambrosio Silva came down with a bad bout of malaria. Dr Rodrigues knew I had some tablets and came with his friends to ask for them. They knew they could not replace nor pay, but I gave them up. I prayed to God.

Later in the year I had a bad series of malaria, about six bouts in a row. After about two months I was down to 80 pounds. Each time my temperature topped 104°F I would hallucinate. Then the Hong Kong Bank sent in a whole lot of Quinine, I was given enough and did not have a relapse.

I believe fervently 'Ask and you will receive' but first you must 'Do unto others, as you would them do to you'. Too many remember the first but not the second. My first job was with a bank and one learns it is easier to get credit if you have a good name. In other words, build a good credit with God and he will look after you in your time of need. There is an old native prayer "Lord thou knowest what I need, for this I pray".

Difficult Times

Early on in camp I contracted scabies. There were two treatments, one long and one short; for both all your clothes had to be steamed.

- You could shower and have a bucket of lime and water mixed and poured over you daily for a couple of months.

- You could strip naked, stand against the wall, get scrubbed down with a stiff brush and have a very hot mix of lime and water poured over you. The brush would scratch your skin and the lime mix would sting like hell. The first day would not be bad, but the next two days were hell. I took the three-day treatment! Some men would faint on the second and third day.

While playing sport, I fell and scraped a square inch of skin off my hip, which turned septic. For a month I used a hot fomentation to try to cure it. This meant boiling a square of cloth, placing it hot over the sore and holding a mug of hot water against the cloth to keep the heat as long as possible. After about six weeks, a medical staff member took pity on me, took me to his room. I stood at the foot of the bed and he took a sterilised needle and dug out all the pus. Then he took from his stock a square of Elastoplast and placed it over the sore. He told me he could not give me anymore as he had only a little left. After eight days I removed the plaster but the wound was still there, though much better.

There were three brothers in the camp who had medical supplies. One of them — let us call him "Miguel", which is not his real name — had taught the camp Sgt Major how to play the piano and through him had got plaster and other medicines. The brothers hoarded these things, saying that after the war things would be scarce and the family would need them.

I knew they had some Elastoplast and I offered to buy one square from them but they refused, so I went back to the application of fomentation and in one month I was OK.

One brother — let us call him "Paul" — was in charge of the poultry farm and contracted an eye infection. The doctor gave him some strong pills, but he only took half as the other two brothers insisted they must be saved for the family. The result was that "Paul" went blind.

Anyway, "Miguel" was bored with staying in camp with nothing to do, so one day he volunteered to go out to work. Not being very used to it, he came back full of aches and pain. He asked me to massage him and I gladly agreed. I promptly tied a knot in his muscles and left him with it. He had to pay a member of the medical staff to massage him. Another time the three brothers, tired of having to wash their mess tins after each meal, decided just to cover them with a cloth. After about a month the cook house refused to serve them until the tins had been scrubbed out: they were green with fungus!

For about a year after the camp started there was no dentist. When Bowen Road Hospital closed, it was announced that a dentist would be attending to patients the following morning. I was there in the morning with about 40 people waiting for opening time. The door opened, the attendant came out and announced "the doctor regrets that he has no painkillers". After that there were only about 3 left - Ernie Ribeiro, Dick Alves and myself. I had a front tooth extracted. Later in the year I had a bigger problem: the filling had fallen out of a back tooth. I was told the tooth would have to come out. We were living in the flats in Jubilee Buildings. I turned up at the dentist's room, he sat me down in a rattan bucket chair, rested my head on the back of the chair and the assistant held my head down with both hands to stop me moving. The crown of my tooth shattered right off, and the dentist had to fish out the three roots of the tooth with no painkillers. After they came out the dentist gave me a pill and told me not to take it until sleep, and said I did not have to work the next day. I took the pill before bed, woke up the next morning and as I was off work I had the job of cleaning the bathroom. Much to my disgust someone during the night had shat all over the floor. Plenty of water and brush fixed the problem, and I found the culprit, me. The pill was an opiate and I was not conscious of the misdeed! Bits of bone kept on coming through my gums for a few weeks.

For a period in 1943, the Japs made us erect wooden sleeping shelves in the huts. They ran the whole length of the hut, 45-50 men to a hut, and each man had two feet of space. The spaces were measured and marked. What a trouble! The wooden beds were made of soft pine. We slept with all heads to the wall. You had to memorise your space; if you needed to go to the toilet in the night, you navigated by counting the windows.

The big problem was that the huts were infested with bedbugs which made our lives a misery. Your mattress was your blanket folded to the two-foot space. I must have spent a fortune on matches, some nights using up to a whole box to light up and kill the bugs running about on the blanket. My friend Sebas Silva earned himself the title of Chief of Night Operations because one night he (a very slim, small man) lay in his bed and suddenly sat up, lit two matches at once and ambushed the bugs coming to attack him. Imagine trying to have a good night's sleep after hard labour and waking 10-15 times a night to kill bed bugs! The worst of part about killing these bugs was that they stank. You had to kill the bugs between your nails and not on your blanket, otherwise your blanket would end up stinking.

One of my friends captured a couple of bugs alive, put them in a tin and in the morning left the tin in the sun. The bugs die from too much heat. He would watch them suffer; when they started staggering around the tin, he would remove the tin from the sunlight, let them recover, then put them out in the sun again. (Don't let the RSPCA know.) Some people were lucky as the bugs did not fancy their blood.

Remedial Massage

One of the scourges of the camp was vitamin deficiency, known as 'electric feet'. The nerves in your feet died and you lost feeling in them. I saw a hammer fall on the carpenter's foot while he was next to me. He said "ouch" but felt no pain. But at night it was hard to sleep, because you had an itch in your foot that was like an electric shock. I used to massage about six chaps each night, kneading their feet. This would help them sleep for two to three hours. My hands were very good at massage for stiff necks, I remember massaging one chap for one hour before I could unknot his neck. In the early days, oldies like Nanelli Baptista would have to go out to work. He would return aching all over and after ten minutes of massage he would fall asleep, leaving me to find and ease the stiff sore spots.

Fitness

It was noticeable in camp that one had to keep active, especially after a sickness. After my bouts of malaria, I got down to 80 pounds, and could barely walk in the first two weeks. As I grew stronger, I took on daily jobs, progressing to harder labour as I got better. A good illustration: I worked often with two brick layers; sometimes when there was a rush on we'd work ten days at a stretch, in good health. The doctor in charge of the hospital wanted these two to work for him exclusively, and arranged for them to report sick and go to the hospital. After a few days of working only in the hospital area, the fell ill and did not get up for two months!

Food for Thought

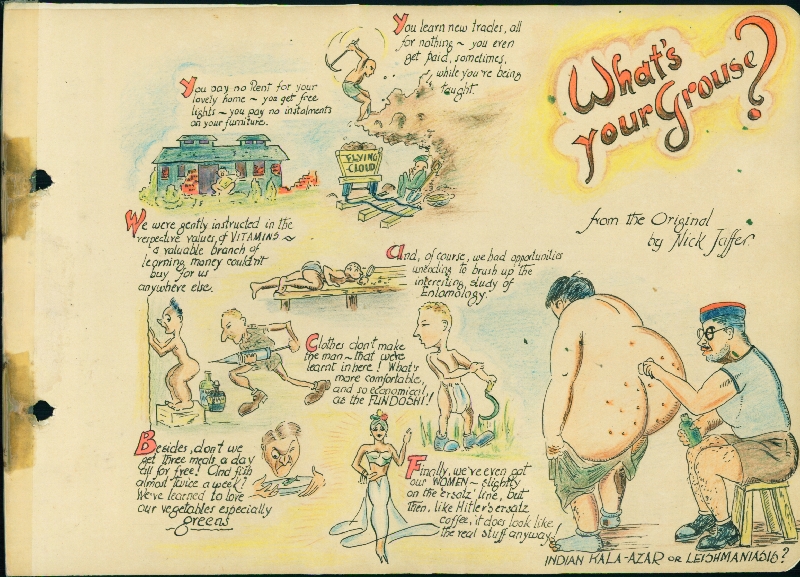

Food filled your thoughts. Rice was a constant part of our diet. Often we had vegetable soup, usually very clear with a few pieces of vegetables floating in it, never much. There was a period when the Japs sent in curry power and bran flakes, raw. The cook house turned out curried bran and rice and the queue at the toilets was long.Red Cross parcels

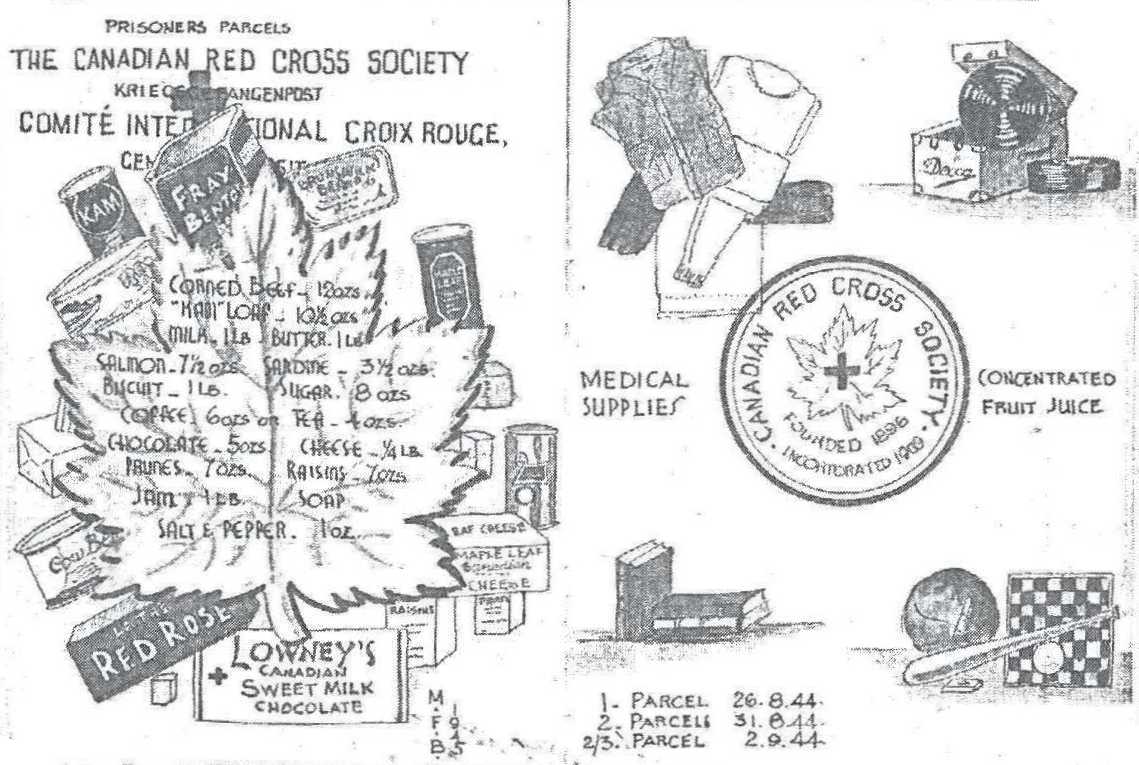

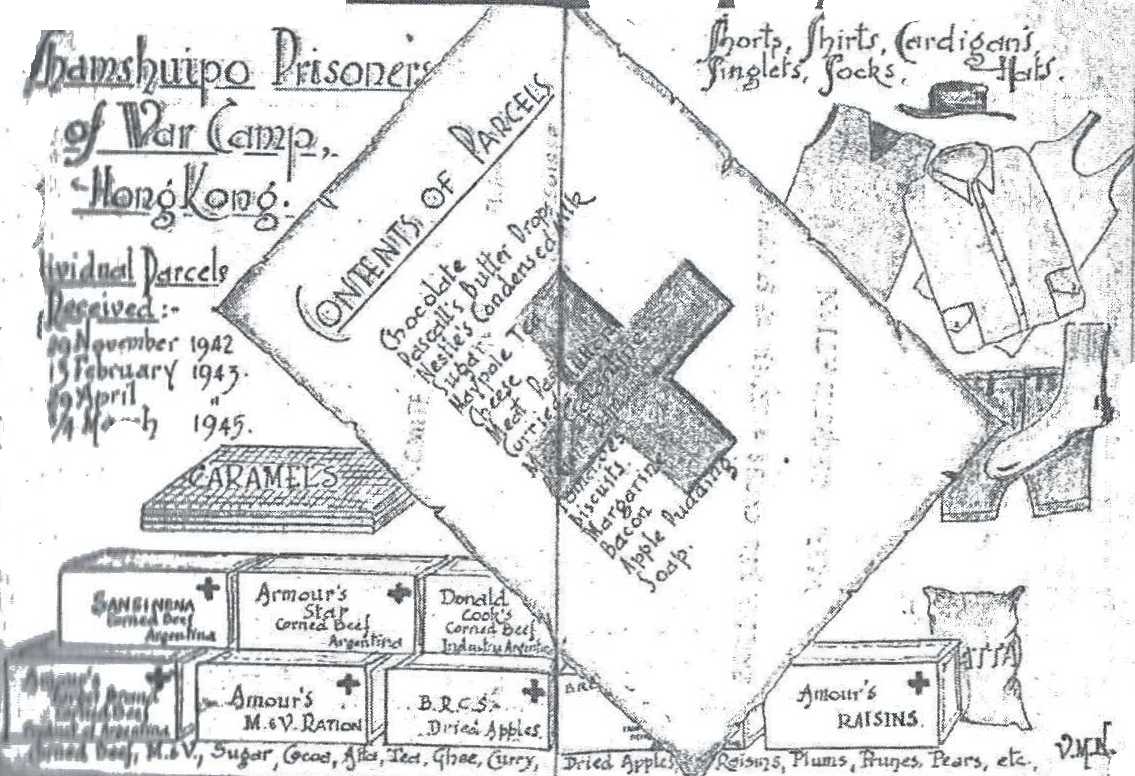

The British and Canadian Red Cross sent in food parcels, but the Japs restricted the distribution.

British parcels distributed: 20 November 1942, 13 February 1943, 29 April 1943 and last three parcels for four men in 1945.

Canadian parcels: 26 August 1944, 31 August 1944 and two parcels for three men 2 September 1944.

There were some funny scenes when the first lot came in. Some men opened everything, ate the lot in one go and got violently sick. The British parcels had tea and margarine, the Canadian had coffee, tea and butter. The coffee powder was awful, we called it Prairie Dust. The British also sent in big blocks of caramel, which was full of vitamins. Caramel was not released to us until 1944. It was allocated to the doctors to dole out especially to men with eye trouble due to malnutrition. My good friend Memie suffered from this; he had to wear sunglasses in the moonlight! Our doctor, a local, would not prescribe caramel to Memie. His excuse was that we (Memie and I) had money and could afford to buy fish oil from the black market, till I found out that the good doctor was dishing out these "sweets" to his friends as candy! I marched into his room and demanded (and got) a good ration for my friend, and he was cured.

The main vegetable you could buy from the black market was garlic. We would pickle the garlic in a jar of soy sauce and use it to flavour the plain rice we were fed. When from the stage I made the audience roar with laughter, I would be almost flattened by the solid waves of garlic-scented breath! Other things you could buy were ducks' eggs and slab sugar. One chap bought a catty (1¼ pounds) of slab sugar and sat on his bed contemplating how to fill the two small tins he had. He decided to put the big pieces in one and the small in the other. So, we watched him, one big, one small, undecided so he'd pop it into his mouth; one big, one undecided, one undecided and ended up with two empty tins.

Once the Japs sent in a quantity of small (five-inch) salt fish, enough for each person to have one. Three-quarters of the camp would not eat the heads, so we Portuguese and Eurasians of the volunteers queued up at the cookhouse to have 2 heads each.

Once when I was in hospital with malaria, the evening vegetable soup tasted a bit strange. We found out later a chicken from the farm had died of starvation, so it was given a bath in the soup and served to the cookhouse workers.

At one stage we had some sacks of green peas sent in. The cookhouse boiled them up and served them instead of rice. They were hard but one could not chew them because the Chinese merchants had shovelled in lots of sand grit. So, the only way to eat them was to swirl them around in your mouth and swallow them, grit and all.

The cookhouse occasionally had cake on the menu, made from rice flour and some condensed milk released by the Japs. The Macanese word for cake is 'bolo'. The cookhouse had a notice board outside where notices of events, like Bridge tournaments, would appear. One day, someone came into the hut all excited, "we have bingo today for dinner".

Our skins, from lack of oil, cracked easily. At one stage only those on work parties were allowed to use soap in the showers. I remember the day when the Japs released tins of ghee. The working party bringing in the ghee included Gerry Gosano and Charlie Thompson, both very fit and burnt black from the sun. The tins leaked badly, so these two smeared themselves all over. Being only in fundoshis, they shone in the sun and could be seen shining half a mile away!

The Yanks are Coming

In late 1944 the Americans sent a carrier taskforce to bomb and harass the China coast. We had several heavy raids and the Japs decided they wanted an air raid shelter built between the Jubilee Buildings and the Sergeants' house which was outside the wire (they cut a hole in the fence). So the Royal Engineers' yard team was mobilised to do the job. It involved digging a trench three metres deep and 25 metres long. Luckily the ground was landfill, so was very easy to dig. Then we had to build a wooden tunnel 20 metres long, one and a half metres wide and 180cm tall, sink it all at the bottom of the hole, build steps at each end, then cover it all with earth. I was the manager coordinating and solving any problems. As we were finishing packing the earth around the tunnel an air raid alarm sounded. We the workers stayed in the open, while the Japs scurried down to the tunnel. They looked funny, trying to hurry without showing too much haste.

At the headquarters the Colonel was so taken with this shelter he decided he wanted one too, so we were given the job. We would be trucked there each morning and marched back at night. The ground was again landfill, more sandy than at Jubilee. I remember one day we had got the required depth, about three metres. The nasty interpreter whom we called 'Slap Happy'Kanao Inouye, a Canadian Japanese who became an interpreter for the Japanese Imperial Army. After the war he was tried for treason and hanged. Andy Flanagan The Endless Battle: The Fall of Hong Kong and Canadian POWs in Imperial Japan (he loved slapping us around) went down the trench to inspect our work. As we stood around, a large part of the trench (being sand) slid down engulfing Slap Happy up to his chest. He went pale as he realised that all of us jumping in to dig him out had pickaxes in our hands.

This work party was enjoyable in that we brought our usual lunch of rice, and the cook at HQ provided us with double the portions of rice. We never sent any back. What we couldn't finish we brought back with us to camp. The only problem with this work party was that after finishing we had to march three miles back to the camp. I would sing all the way as it made it easier. Our road back was along Prince Edward Road, and just before the Rail Road Bridge was my cousin's house which had a big lawn in front. This was rented out as the Jap NCOs Mess and usually had a few of them hanging out to see us go by. This was early 1945 and the Yanks were definitely winning. I was feeling bloody-minded and started singing loudly, "Over there, over there, for the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming", etc., as we went by. None of the Japs reacted as we went our merry way. But someone in the work party told RSM Jones and for the next three weeks I went out everyday on different work parties and the Kempetai (secret police) came in every day to look for me. So I went about eight weeks with no break. Worth it!

War's End

We were not told of the end of war for two or three days. A group of us — Alves, Delano and Lolly Lopez, myself and two or three others — used to gather outside our hut on hot nights and chat. On the night when the war ended, 'Lights out' was early and it was pleasant at the back of the huts fronting on the main road, so we were out there when we heard a wave of sound coming towards the camp from the city which was under strict curfew. It was a vague roar that jumped from one block of flats to the next, as no one was allowed on the street. The noise grew as it got close to the camp and we could see the sentries at the gate, 100 metres from us, getting agitated, so we decided it was safer to go in, out of harms way.

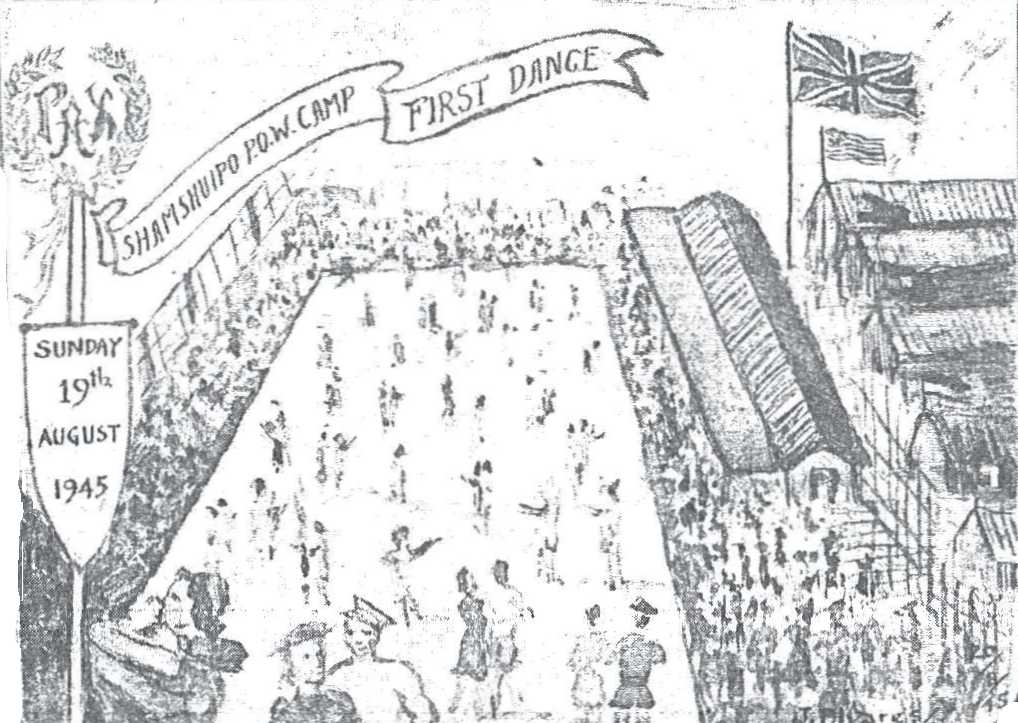

The next day the working party went out and came back early, saying people were shouting "the war is over". The following day, the working party refused to go out, and we demanded to see the Camp Commander. He reluctantly confirmed that the war was over. The day after that, civilians started coming to visit, some good food started coming in and we had meat in our meals. The next day, the 19th, we had a party and friends and relatives came in and some of us, amongst them Edo Silva (my brother-in-law) went over to Hong Kong to Rosary Hill to visit their families.

The people from Stanley sent word that they had agreed with the Japs that they would maintain order until the British fleet arrived. It came in on 30th August. We were having another party in the camp, and my friend Albert Leonard came to me and suggested we go and see the fleet. We got on two bicycles and made our way to Holts Wharf on the Kowloon waterfront. Albert got off the gangplank of a Canadian ship as I stepped on the gangplank, and I did not see him again till it was time to get off three hours later. There were about twenty of us POWs on board so the cooks prepared a feast for all of us, after the rot we had been served. I remember two slices of bread from a loaf eight inches high; butter aplenty, two chicken drumsticks (the size of turkey), pudding and two big lumps of ice cream. I had half an inch of butter on the bread, enjoyed the chicken, vegetable and pudding, then could only look at the ice cream, as the food was too rich. Before the fleet came in, we had planes dropping supplies, including scented soap and the huts positively reeked of the scent.

Back at the ship, we would have a drink of rum with one group, then move on to the next, walking all over the ship. At one stage I noticed I was lifting my feet rather high as I walked, I only had sandals on, no socks. I started the evening refusing cigarettes, till I got fed up and took one, and I had a lit cigarette in my mouth the rest of the time. I got back to camp about midnight, well lit, and woke up the next morning, surprisingly well, except for a sore toe. I took a look and found my big toe had lost half its toenail. It was the reason for lifting my feet high the night on board; there was no pain then with all the rum we had drunk. What a night! We finally left the ship and started walking home and Albert deviated and led me along Kimberly Road and knocked on the door of an apartment. To my surprise it belonged to Ina Carvalho and Nina Lopez. We had a chat and a drink and left, picked up two bicycles and went home.

After a few days the local volunteers were taken by truck to May Road on the Island where we were billeted in empty houses. The water supply was damaged and, as it was summer, we washed ourselves in the stream which came down the mountain. I remember washing myself all alone late one night when I felt something coming up my lower leg. Looking at it in the moonlight (there was no street light) I saw a ruddy ten-inch-long centipede on my calf. I carefully manoeuvred myself in the stream so the beast was washed off.

They offloaded some more commandos and soldiers as garrison and they took over the running of Hong Kong. A couple of transports were emptied and the British and the Canadians were loaded to go home. We, the Portuguese were billeted in May Road, issued new clothes, with regular fortnightly pay and nothing to do. I was with a group of friends, Alex Pierce, Micky and Luigi Remedios, Gussy Ozorio, Josim and one other. We did a bit of carousing and drinking. Charlie Gray soon had his nightclub working and we were often there. I think Edo Silva (my brother-in-law) was up at Rosary Hill with his wife (my sister). Their apartment in Prince Edward Road was looted down to the floor boards, and they had lost everything early in the war. I soon stopped going with my group and also lost sight of my friend, Memie Gonsalves because he was in Field Ambulance and was billeted elsewhere. I started a habit of going on board Navy ships for my evening meal and they would generously give me a tin or two or three to take away. Consequently, I acquired a clean rice sack and stored these for a 'rainy day' when I went home. I acquired so many, the bag was 100% full. Neither my brother Bill or future in-law Flavio could carry it on our visit to Macau to meet our family even though they were both taller and heavier than me.

Back to Civilian Life

When the Fleet came in on 30th August (Liberation Day) we were still in the camps and the Japanese, by agreement with the Hong Kong Government officials, maintained order in the city. We were eating better; we had meat from contractors and we had visitors between camps and from civilians who stayed through the Occupation. Discipline was lax, though there was a curfew on the population. The Japs would not stop anyone in our ragged khaki uniforms. Transport was on the back of a few bicycles, paid for in Jap occupation yen. A week after the fleet came in we were shifted from the camp, given new uniforms and billeted in empty houses in and around May Road (Mid Level). The water supply was damaged so we washed in the plentiful streams coming down the mountain. The banks and a few business houses started up. The Hong Kong Bank where I worked got going immediately but I did not feel like work so I stayed away, doing a lot of drinking around (as a Corporal I could buy a lot of whiskey at the canteen). On Hong Kong Island the trams were working. There were a few incidents, mainly people identifying jail staff and torturers and handing them in to the occupation forces. I remember one notorious torturer who was taken from a tram and literally torn to pieces in the street. After a couple of months of loafing I started work again in the Bank. Meanwhile, in I think late September, the government organised a trip to Macau aboard a frigate for those of us whose relatives were there. (They were not allowed to come back as Hong Kong was still in chaos.) We had 4 or 5 days there, then returned to barrack accommodation. I amazed my brother Bill and future in-law Flavio with the ease with which I carried my sack of tin goods, which neither could handle despite being taller and heavier. We enjoyed our stay.

About this time, the administration in Hong Kong found it necessary to bring approximately 15 unmarried ladies from Macau to work as secretarial staff, among them my sister Lolita (Lolly). They were housed in the French (Catholic) Mission building in Garden Path. Lolly was allotted to work for the Commodore-in-Charge of Hong Kong.

Stood Down

Meanwhile in November 1945 we were officially stood down from active service. We were paraded before the doctors who had been in the camp with us, asked a few questions as to how we were and handed our discharge papers. Although there was a fully equipped hospital ship empty in the harbour, we were not taken there for a proper medical examination.