An account This has been edited into a form suitable for website, with images and links to Personal Pages added — HdA (Ed.) of my war experiences

and subsequent imprisonment under the Japanese

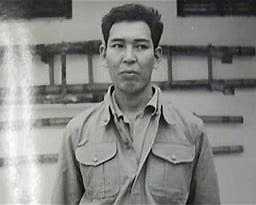

Luiz "Luigi" Vieira Ribeiro

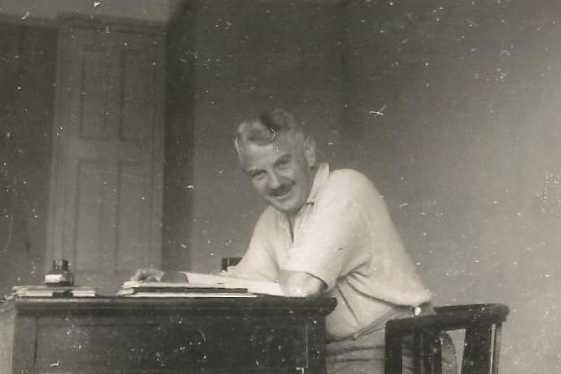

December 1941 to August 1945This transcription was made in January 2016 from the carbon copy of an unsigned typescript, of which the top copy evidently went to Dr Roland. Luíz Ribeiro carefully corrected the typescript, and his corrections are incorporated in this transcription. Here and there I have added annotations, which are inserted into the text in square brackets, rather than rendered as footnotes. A very few small errors have been silently corrected, such as a misspelling of Dr Roland's name (typed as 'Rowland'). Most references to the Bank are to its full name, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp. On a few occasions, Ribeiro used an ampersand (&) rather than 'and'. The officers of the Bank were very particular about this, and also of the use of 'Hongkong' as a single word, as its name had been registered that way in 1864.

As far as I can recall, the typescript came to me from my uncle, Tony Braga, who was also a member of the HKVDC Field Ambulance.

Stuart Braga, Sydney, Australia 17 January 2016

written ca. 1987 at the request of

Dr Charles Roland, Canadian medical historianCharles Gordon Roland was born on 25 January 1933 in Winnipeg, Manitoba. After a long and distinguished career as an author, editor, and Hannah Professor of the History of Medicine at McMaster University, Dr. Roland died at the age of 76 on 9 June 2009 in Burlington, Ontario.

His research interests focused on medical aspects of World War II, culminating in two seminal books on the Warsaw Ghetto and on Canadian prisoners of war of the Japanese in the Far East, Courage Under Siege: Starvation, Disease, and Death in the Warsaw Ghetto, Oxford University Press, 1992, and Long Night's Journey Into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941-1945, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2001.

Biographical note

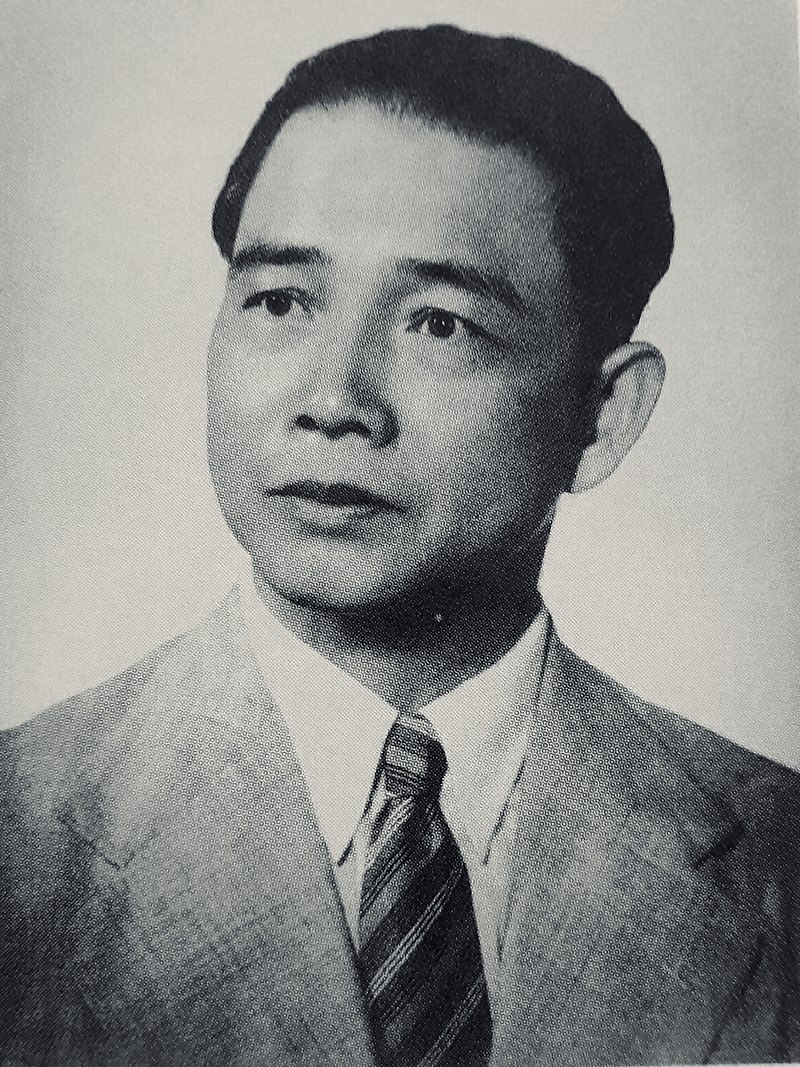

Luiz ('Luigi') Ribeiro was born in Hong Kong on 11 April 1909, the eldest of three sons of Francisco Xavier Vieira Ribeiro Jr, and Maria DoloresMaria Dolores, née de Sousa. He was therefore a British subject by birth.

He was clearly well educated, as his English is very good indeed, with several literary allusions and good command of idiom.

He was a clerk in the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, rising in the 1930s to the position of Chief Clerk in the Foreign Exchange Department. He enlisted in the Hongkong Volunteer Defence Corps in the Field Ambulance, and was on Active Service from 11 December 1941 until the fall of Hong Kong on 25 December 1941.

He was imprisoned in Shamshuipo Prisoner of War Camp from 30 December 1941 until the Japanese surrender in August 1945. He was passionately loyal to the King, as his reaction to the hoisting of the Union Jack at Shamshuipo Camp in August 1945 makes clear.

After the war, he returned to his position in the Bank. In October 1961 the Lusitano newsletter, published in Hong Kong, included his name as one of the first group of fourteen senior Portuguese clerks to be appointed as officers of the Bank, bestowing on them executive responsibility hitherto confined to the British staff. This was a major step forward, not only for this group of senior officers, but for the whole Hong Kong Portuguese community.

His parents fled during the Japanese Occupation to Macau, where his father died on 4 December 1944. Together with other Portuguese members of the Volunteers, Luigi visited family members in Macau in September 1945. On 12 November 1949 he married Dorothy Millicent née Ló. There were no children. During the 1980s, Luigi and his wife visited his old friend Clementino Leonardo Lopes in a nursing home in San Francisco. 'Lolly' Lopes had been broken in health as a result of war-time privations and illness.

On Luigi's death in Hong Kong at the age 84, Robin Hutcheon, the former editor of the South China Morning Post wrote:

Luigi F.V. Ribeiro, who died in Hong Kong on Sunday morning March 20th, was a courageous battler for the rights of Hong Kong belongers. A British subject whose family came from Macau many years ago, Luigi was born in Hong Kong and educated in Macau before World War II. When the Pacific War broke out, Luigi joined the Hong Kong Volunteers as an ambulance assistant and a stretcher bearer because he was a conscientious objector. He nevertheless served in the thick of fighting, rescuing wounded comrades and was taken prisoner with other volunteers at the surrender.

After the war, he became a correspondent for the South China Morning Post. Later he put his pen to work in the interest of volunteers, pleading for full British nationality and resident's rights in the United Kingdom. He wrote tirelessly, not only to newspapers, but to the British Prime Minister, the Foreign Secretary, the Hong Kong Government, the Chief Secretary and Legislative Councillors. When the right was finally conceded he was quick to denounce the British Government's failure to extend the same right to the wives of former PoWs.Prisoners of War

Luigi was a vigorous campaigner who gave no quarter but was bitterly disillusioned by the failure of the British Government to recognise the sacrifice of young Hong Kong volunteers who endured four years of privation and hardship in Japanese camps in the service of Hong Kong and country.

An example of his long campaign was a letter to the editor of the South China Morning Post, published on 15 September 1987, protesting strongly about the poor treatment meted out to the Portuguese personnel of the Hong Kong Volunteers and their dependants. It had taken more than forty years of effort for a small number of survivors or their widows to be treated with equity, and then only because the British Government had been generous to some 20,000 Gibraltarians and 1,500 Falkland Islanders in the matter of granting them British citizenship.

Stuart Braga, Sydney, Australia 17 January 2016

The following is a personal account of Private LF Vieira Ribeiro, No. 4210, Field Ambulance unit, Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, rechristened The Royal Hong Kong Regiment (The Volunteers) from the time he enlisted in that unit to the time he was freed from Shamshuipo PoW Camp where he was interned for 44 months under the Japanese until finally liberated by Rear Admiral Harcourt's powerful naval forces on 30 August, 1945.

The account of my war experiences and subsequent imprisonment under the Japanese is being undertaken at the behest of Mr CD Roland, MD, Jason A Hannah Professor of the History of Medicine at the McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Professor Roland, a medical historian, is particularly interested in my duties as a PoWPrisoner of War, unusual cases that I had observed, drugs and supplies available and diseases experienced.

Not having myself kept a diary of events in camp during these eventful years there, it is well-nigh impossible from this distance in time to pinpoint dates of events, memory being such a treacherous and unreliable thing.

The keeping of a diary in camp constituted a serious offence in the eyes of the Japanese and there was no telling what the consequences might have been if one was caught in possession of such incriminating evidence.

However, by cross-checking events and their respective dates by patiently going through with a fine comb a few of the war books I have on the fall of Hong Kong and the internment of its garrison and then to the forbearance of several of my fellow-PoWs with more dependable memories than mine I was able to restore a semblance of coherence and chronological order to my narrative.

Britain had a mutual defence pact with Poland, but when Hitler's panzer divisions knifed through the Polish Corridor on 1 September 1939, true to her word, she declared war on Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939.

Britain's declaration of war against Germany sparked off in Hong Kong a spontaneous display of loyalty to the mother country as able-bodied young men of all races, colours and creeds from all walks of life rallied to the colours.

The very thought of killing my fellowman, be he friend or foe, was abhorrent to me, so the only way I could do my bit for King and Country was to enlist in the Field Ambulance of the HKVDC, known in short as The Volunteers.

The regiment was and still is a self-sufficient miniature division with supporting ancillary units, whose men of yesteryear and today come from a wide cross-section of Hong Kong's cosmopolitan society in a mix of all the professions and trades, where everybody had and now also have an important role to play.

Regular army instructors trained the part-time weekend civilian soldiers at Volunteer Headquarters after office hours in their respective martial skills. Those with higher aspirations to being N.C.Osnon-commissioned officers or gentlemen and officers had to put in much more time than the compulsory one evening a week of training.

There is a popular barrack saying which assures every soldier on joining up that at the bottom of every private's kit bag there is a field marshal's baton. If that be so, the quartermaster bloke certainly omitted to include this item in my kitbag when I joined up, for I ended as undistinguished as it had begun, my martial time as a humble private, the lowest form of animal life known in the army.

Every year during Hong Kong's called dry winter months the men of the regiment lived under canvas for two weeks in the New Territories during which they underwent rigorous military training and took part in mock war exercises. It was the litmus test of how much each man had learned during the year from all his instructors.

As a private I soldiered for two shillings and sixpence a day, a shilling being the equivalent of eighty cents in our currency. Thus I brought home the princely sum of $28.00 Actually, if 1s = $HK0.80, 2s 6d = $HK2.00 - Ed. for my fortnight's pretence at playing at soldiers.

On 8 December 1941 at 8 a.m., I was just about to leave the house as usual, to cross the Harbour on the Star Ferry to report for work at the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, when the phone rang. In an excited voice my younger brother Gilbert blurted out: "Luigi, Japanese fighter bombers have just bombed the RAF installation at Kai Tak airport". This naked act of aggression signalled the opening of Japan's undeclared war against Hong Kong.

Before I could recover from the shock of the news, an announcement came over the radio. The voice said: "Will Staff who are in the essential Services Group of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank report immediately to the Bank and not to Volunteer Headquarters?"

I reported, as instructed, to my department at the Bank building in CentralCentral District, Hong Kong. It dealt with Foreign Exchange, which covered all outward remittances. Apparently my other departmental colleagues had not heard the wireless announcement for I was the only soul present.

Before long Sir Vandeleur Grayburn, Chief Manager of the Bank, came to my department. Said he: "Mr Ribeiro, you are the only one, I see, who heard the radio announcement. I am glad you've turned up for we shall be frightfully busy very soon. All surface communication with the outside world has ceased. The only way of getting money away is by telegraphic transfer. You will be swamped with TTTelegraphic Transfer (of funds) applications from firms wishing to get their money to safety elsewhere. I know you've not done TTs for years now, but I am sure you've not forgotten how to despatch them. You estimate cost of cable charges and debit customers' accounts accordingly. This will save valuable time by not sending individual applications to Telegram Department for assessment of cable cost on each TT".

I heaved a sigh of relief when the department's faithful No. 1 Boy hove in sight, because he would be of great help to me later in the day with the stamping of the relevant TT confirmations. Because of the vast sum of money which may be involved on each T.T, stampingThe actual stamping of the TT confirmations was done at the end of the day's work, when I assessed and handed the Boy the exact amount of stamps on each TT confirmation and he would affix the stamps thereon and cancel them with a heavy chop to prevent them from being illegally re-used. The franking machine did not exist in those far-off days. being calculated ad valoremin proportion to the estimated value of the goods or transaction concerned, duty on each TT could run to thousands of dollars.

Every hour or so Sir Vandeleur would pop into the department to see how I was doing. Hard as I worked, I did not seem able to dent the huge pile of TT applications. The big boss was most understanding. He said to me: "Do as much as you can, Mr Ribeiro. You are doing a fine job".

When the day's last TT confirmation had been stamped, I locked the stamp box in my steel drawer and left the Bank for home on the other side of the water. It was already 6pm I had had an exhausting day.

There was not a khaki uniform to be seen in the motley crowd and I had the uneasy feeling that people were thinking of me as a shirker, while the gallant lads were engaged in mortal hand to hand combat with the Japanese invaders at the front lines.

The 9th and 10th were a repetition of the 8th with me fighting a losing battle to keep up with the avalanche of TT applications that arrived from firms in a last desperate bid to get their money away from the grasping clutches of the Japanese.

On the morning of the 11th December, just before I called time off for a quick sandwich and a hot cup of coffee, which I had brought with me in a thermos flask, Sir Vandeleur came to me and said: "Mr Ribeiro, Kowloon has fallen and the Japanese have severed cable communication with the outside world. No TTs may now be despatched and you may report to your battle station. You have been a great help. Good luck to you, Mr Ribeiro."

It was the last time I saw alive one of the great Chief Managers of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank. He and his deputy, Mr DC Edmonston, were accused by the Japanese of complicity in an espionage ring and both were sentenced to 100 days imprisonment at Stanley Gaol, where they perished of ill treatment.

Earlier on, the Bank's two topmost executives had refused to play ball with the Japanese who wanted to know how large sums of money had been withdrawn from the Bank. In fact, the money was subsequently used by Dr. Selwyn-Clarke, then Director of the Medical Department, to buy much much-needed food and drugs for the internment camps and hospitals, where the mortality rate would certainly have been even more appalling had the much-needed funds not have been available.

I reported for duty at Volunteer H.Q. on the afternoon of 11 December and was taken by transport and posted to Wanchai Gap, where the Field Ambulance had a medical post under the command of a regular army officer, Capt Worrall, RAMC.

It was not surprising that Kowloon fell in three short days after the Japanese launched their attack with three crack regiments, namely, the 228th, 229th and 230th, backed up by powerful air and naval support.

Now turn to the bleak picture of the defenders. At the most crucial juncture of its history Hong Kong had no navy to speak of to defend its long coastline. Months before the balloon went up here, naval units, normally based here, had been systematically withdrawn to reinforce other embattled theatres of war, leaving the superannuated and under gunned river gunboat Cicala, the frigate Thracian and a gaggle of motor torpedo boats to defend Hong Kong against the might of the Japanese Imperial Navy. Cicala and Thracian were sunk in the early stages of the war by enemy aerial bombing.

In similar fashion the RAF was left with a few token obsolete flying crates which were caught like sitting ducks on the runway at Kai Tak and destroyed in one fell swoop by Japanese fighter bombers in their sneak attack on 8 December. Thus, from the word go, the Japanese enjoyed an undisputed naval and air superiority over their enemy.

In stark contrast, from the defenders' perspective, the picture could not have been more bleak or depressing. They were bombed incessantly from a clear and unchallenged sky during daylight as well as being mortared and shelled by heavy siege guns with hardly any let-up.

To add to the general gloom, on the morning of the 10th December the people of Hong Kong awoke to be shocked by screaming headlines splashed across the front pages of the local newspapers which proclaimed the sinking of Britain's two capital ships, namely, the Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese torpedo-carrying planes in Malayan waters. The depressing news adversely affected the morale of the troops engaged in an unequal fight against a ruthless enemy on the mainland.

The Japanese made two separate peace overtures, the first on the 13th December and the second on the 17th, both of which were spurned by the Governor, Sir Mark Young. In retaliation for the snubs, the Japanese silenced on 13 December a 9.2-inch gun at Mount Davis fort and Belcher's Fort received direct hits from Japanese long range artillery.

On the 15 December the Japanese from gun positions along the Kowloon waterfront put out of action by artillery fire with uncanny accuracy pillbox after pillbox of machine guns on the northern shore of the Island. Their intelligence people had supplied their gunners with maps showing the exact location of each pillbox.

At night pro-Japanese Wang Ching Wei Wang Ching-wei was a Chinese politician who served as a puppet for the Japanese. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wang_Jingwei agents directed enemy artillery fire by flashing signals with torchlights which gave the Japanese gunners the vital co-ordinates which enabled them to zero in on their targets.

agents directed enemy artillery fire by flashing signals with torchlights which gave the Japanese gunners the vital co-ordinates which enabled them to zero in on their targets.

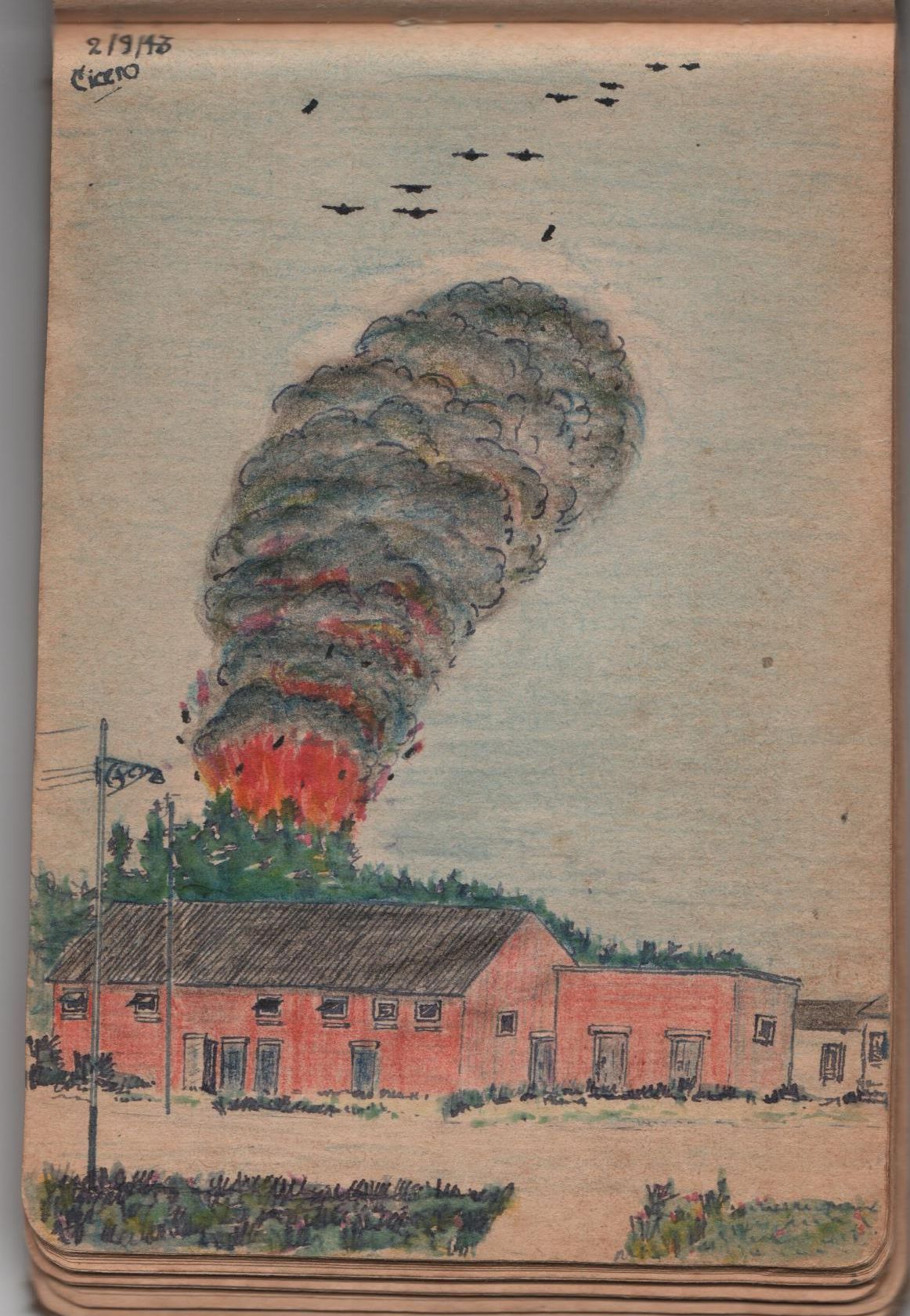

Japanese artillery fire set alight on 18 December oil storage tanks at North Point. A huge pall of black smoke spiralled thousands of feet into the sky. And this, aided by a heavy rain storm, provided the 228th, 229th and 230th Regiments, which had done such an efficient job of snuffing out all enemy resistance on the mainland in three days, with the ideal conditions for landing on the island. It had been preceded by intensive bombardment and divebombing by wave after wave of fighter bombers on observation posts, small craft of every description gathered under cover of darkness to ferry the storm troopers across the narrow expanse of water separating Kowloon from Hong Kong to a designated landing area in North Point near the Hong Kong Electric Company's power plant.

The three Japanese regiments, having successfully made landfall, the divisional commander, Lt Gen Sano), took over operations command. The invaders lost no time in fanning out in different directions with the objective of cutting off the defenders into tiny, isolated pockets and then mopping them up piecemeal through sheer weight of numbers and decisive fire power.

A second wave of three more battle-hardened regiments followed in the wake of the successful initial landings. Thus the Japanese unleashed two seasoned divisions of 20,000 men each which were well-equipped and stoutly supported from the air and sea, besides having a strategic reserve of another two divisions on the mainland, just in case things did not pan out according to plans. Against such overwhelming superiority in numbers and weight of metal the local garrison could muster only 12,000 men poorly equipped and without air and naval support. It is not the purpose of this exercise to get more than necessarily involved with the detailed progress of the Japanese advances on the various war fronts.

Now let us return to the Field Ambulance's medical post at Wanchai Gap, to which I reported on the afternoon of 11 December under Capt Worrall, R.A.M.C. With Kowloon securely in Japanese hands, they positioned their field guns along the waterfront and from there proceeded to shell military objectives and strategic positions in Hong Kong at their whim.

One large building not far away from our post on a hillock overlooking the harbour came in for close attention of Japanese gunners. We were subsequently told that it housed the H.Q. of some Canadian unit. Japanese artillery units were kept up-to-date by fifth columnists who informed their masters of any changes of positions of high-ranking military personnel.

With clocklike regularity, beginning as early as 8 a.m. droves of Japanese bombers flew into Hong Kong skies in tight formation well above the reach of our anti-aircraft guns to drop their lethal loads on preselected targets. They came and went with disdainful impunity during the day, leaving death and destruction in their wake. And we had to grin and bear it because there was nothing we could do about it as we did not have fighter aircraft. A respite from the carnage from the air came only at nightfall, because so far as the Japanese pilots were concerned at the time the technique of night bombing was still in the womb of time.

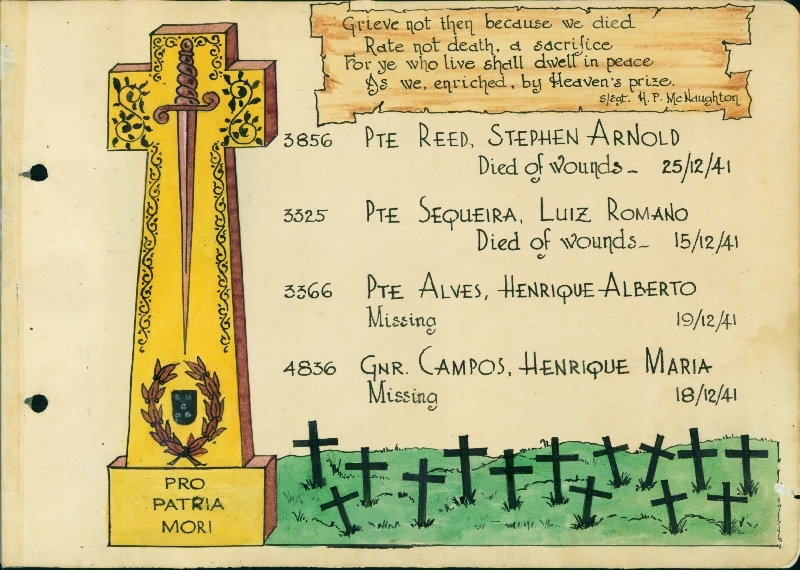

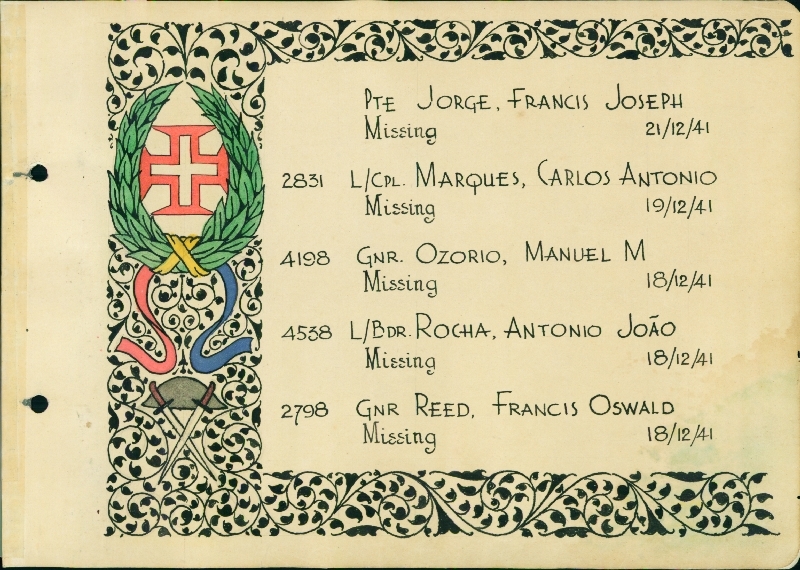

Once the Japanese regiments landed at North Point on 18 December they spread across the countryside like an army of unstoppable marabunta ants from the Amazon jungle, leaving a swathe of death and destruction in their wake. The Japanese troops were veterans of jungle warfare and masters of the art of camouflage. They wore light, sensible rubber-soled shoes with canvas uppers and moved about in the dark stealthily, unlike their adversaries, who wore heavy, hob-nailed boots whose loud metallic crunch gave away their presence from a great distance in the dead silence of the night. How many of our troops met silent deaths at the hands of these shadowy warriors will never be ascertained. Two Portuguese volunteers, Ptes Dickie Alves and Carlos Marques, I was told, were on a night patrol, but were never seen again. The chances are that they had been ambushed and killed by these ghost-like killers.

The wounded started to pour into our medical post from the 19 December until the late evening of the 23rd, when we received orders from H.Q. to evacuate forthwith. The Japanese had broken through our tenuous defences and would soon be overrunning our position.

As the island was swarming with Japanese bent on mayhem and murder from the moment they set foot on it, it would have been suicidal to send stretcher parties in the inky darkness over uneven terrain to bring back the wounded from the scene of fighting.

Just imagine my feeling, when on arrival at my post at Wanchai Gap, the Company Sgt. Major handed me a greasy Lee & EnfieldThe Short Magazine Lee-Enfield Mk III saw extensive service throughout the Second World War as well, especially in the North African, Italian, Pacific and Burmese theatres in the hands of British and Commonwealth forces. Wikipedia, 6 January 2016 rifle and said: "Private Ribeiro, don't lose your rifle; it may be your best friend should you come face to face with a Nip".

Dumbfounded, I held the greasy rifle in my hands, not knowing what to do with it. A good Samaritan in the person of a Portuguese named Pte Álvaro da Roza who had recently transferred from an infantry unit to the Field Ambulance, took pity upon me and came to my timely rescue. He started by helping me degrease the rifle. With consummate ease he dismantled the rifle into its component parts, while explaining to me in words of one syllable the function of each part. He afterwards patiently showed me how to put the parts together; where the safety catch was; how to load and reload; how to adjust the sight and take aim and, ultimately, how in extremis to fix the bayonet for a hand-to-hand combat with the enemy for the grim right of survival.

The irony of it all was that I had purposely joined a mercy unit to avoid having to use a rifle for a murderous intent and there I was receiving an eleventh hour maiden lesson on how to fire a rifle in anger and how to fix a bayonet with the final object of running the cold steel through the body of a fellow-man in self-defence.

I thank God that there is a divine providence who looked after me, born all thumbs, who saw to it that I did not have to fire a single shot in anger throughout the period of hostilities. I am convinced more than ever even today that had I been confronted by the enemy he would have riddled my body with bullets while I was still fumbling with my rifle.

On the day of mobilization the 'medics' were ordered to carry rifles in self-protection on sentry duty or in the discharge of any mission of mercy on the battle field as Japan, not being a signatory to the Geneva Red Cross Convention, would not respect the non-combatant status of members of the Field Ambulance, wherever its combat troops encountered the former.

On the night of 22 December I was ordered by Capt Worrall to accompany an ambulance with a full load, of wounded men to base hospital at Rosary Hill several miles away. I left my post with the mandatory rifle slung across my shoulder. It was to me more a damned nuisance than a help. I sat next to a young Cockney driver who had been assigned to us for duty that evening from one of the many units that made up the local garrison. It was dark and the headlights of the ambulance were doused in conformity with wartime regulations.

Hardly had the ambulance travelled more than a hundred yards when the driver informed me that he could barely see the road ahead of him and that he was not an experienced driver.

I was at the time in my early thirties and fairly fit. I did not at all relish the idea of ending my young life ingloriously at the bottom of a 200-ft ravine with a broken neck. I told the driver to stop and then told him that I would trot along in the middle of the road slightly ahead of the ambulance to guide him along. Luckily it was downhill almost all the way till we reached the hospital at Rosary Hill under the command of Lt Col LT Ride, O/C Field Ambulance.

Just as I was about to leave with the empty ambulance to return to my post Col Ride rushed out just in time to stop me. He told me that word had just come through that a fierce engagement was taking place in Aberdeen between our forces and Japanese troops who had just landed and that heavy casualties were expected. He then ordered me to go to Aberdeen with the ambulance and bring back any wounded. I told Ride that my orders from Capt Worrall were for me to return immediately to Wanchai Gap after delivering the wounded at Rosary Hill. Ride retorted that he would square me with Worrall and to proceed immediately to Aberdeen.

After travelling for some time on the road the ambulance spluttered to a stop. The driver turned the ignition key several times, each time for long spells, yet the engine stubbornly refused to come to life. He jumped from his seat to the ground, lifted the bonnet of the car and shone a beam of light from a torch on each spark plug, but was satisfied that every one was connected. He then turned to me and asked if I had any suggestions which could help to which I replied with a curt "No".

There we were stranded in the middle of no-man's-land at an ungodly hour of the night with the uneasy feeling that the countryside was swarming with drugged, blood-thirsty Japanese storm troopers raring to kill as many enemies as possible for the great honour and glory of their divine emperor. We waited for fully 15 minutes, but nothing happened. Impatient from waiting, the driver told me he was going to enlist help and left me to guard the ambulance. I never saw the driver again and wonder to this day if he had been liquidated by one of those phantom-like killers trained in jungle warfare.

Left alone in the wee hours of the morning with a rifle I did not know how to use, I was assailed by all kinds of imaginary fears and doubts. After staring into the unrelieved darkness for some time, I began to hallucinate and saw Japanese troops popping up from hedges and vanishing in the murky darkness of the paddy fields which formed the backdrop.

After what to me had seemed an eternity of waiting, suddenly I detected in the still of the night the sound of distant throbbing of a motor car engine heading in my direction. I jumped from the ambulance and stood in the middle of the road brandishing my rifle frantically. Thank God it was, indeed, an ambulance returning from Aberdeen, the scene of an engagement, with wounded soldiers. The driver spotted me and stopped. I hopped on board and sat beside him and while on our way back to base hospital put the driver in the picture concerning my misadventure.

When I arrived at Rosary Hill sanswithout my ambulance, I explained to Col Ride what had happened on the way to Aberdeen. He accepted my explanation and told me to get some sleep, promising that he would be sending me back to my post by the first available transport in the morning.

On arrival at my post at around 9 a.m. on 23 December I was confronted by a visibly irate Capt Worrall, who peremptorily asked me: "Pte Ribeiro, where is my ambulance and where have you been all night?", his voice rising in a crescendo of unsuppressed anger. Obviously Col Ride had pocketed my request about informing my commanding officer of his decision to send me with the ambulance to Aberdeen. Later in the day, when Worrall had calmed down, I recounted to him what had actually transpired the previous night and peace was once again restored between commanding officer and private Ribeiro.

As soon as Kowloon fell into Japanese hands they turned off the water supply to Hong Kong, for which historically the island had been and is still largely dependent on Kowloon for. By 23 December the island's reservoirs, too, were in Japanese hands and they were promptly turned off with the object of applying additional pressure to bring Hong Kong to its knees.

On the night of the 23rd December Capt Worrall received orders to evacuate Wanchai Gap with all the men and equipment because the adjacent area would soon become militarily untenable. The men were ordered to make their way separately on foot in groups of twos and threes and head for Victoria Mansions, the new HQ of the Field Ambulance at the Peak. The men were further ordered to take with them as many rifles and bandoliers of ammunition that were left behind by the wounded to prevent them from falling into enemy hands.

I was lucky to be paired with Pte Álvaro da Roza, the Good Samaritan who earlier had given me my one and only lesson on how to handle a rifle. No pathfinder, I would have got hopelessly lost in the dark during the long dreary trek amid the utter chaos and confusion of retreat miles before I got anywhere near my destination, while my companion knew the way to H.Q. like the back of his hand. His familiarity with the topography of place came from the fact that he had been matey with the Quartermaster bloke and often accompanied him on the ration truck when he went on his daily rounds to distribute rations to the men in the various medical posts scattered hither and thither.

When we started on our heart-breaking retreat, Ptes Roza and Ribeiro looked like two walking Christmas trees each with half a dozen bandoliers draped round the necks and a rifle on each shoulder. After trudging along for a mile, the bandoliers began to weight us down and we cursed them under our breath. When we reached a road overlooking a deep ravine with an exuberant undergrowth of vegetation we relieved ourselves of three bandoliers each by jettisoning them into the yawning chasm below.

At the next stop half an hour later my partner removed the bolts of both my rifles and those from his and we threw them as far as we could into the thick vegetation which swallowed them far below the road and discarded the boltless rifles elsewhere along the route in similar fashion. By the time we reached the promised land we had relieved ourselves of all our encumbrances. We reported our arrival to the NCO on duty and were told to get some sleep. It was around 3am. Dog-tired, we slept the sleep of exhaustion. It was indeed a night which has been indelibly etched in my mind.

Lest I forget, I wish at this juncture to pay a humble private's tribute to the brave chaplains of both persuasions, Church of England and Roman Catholic, for bringing spiritual comfort to the troops, wherever they might have been, very often under heavy artillery and mortar fire at the gravest risk to their lives. When the RC padre visited our post at Wanchai Gap, chaps who had strayed from the straight and narrow path for years made their peace with God by the road kerb, padre and penitent both wearing protective steel helmets against flying shrapnel.

With the exception of several bombs which narrowly missed Victoria Mansions and exploded harmlessly hundreds of yards down the slope of a ravine nothing untoward happened. It was during the brief lull at Victoria Mansions that I managed to contact my parents by phone. They had evacuated Kowloon just before it fell into Japanese hands and were staying with relatives in Happy Valley. We were all so immensely relieved to find out that all of us were well and in one piece. That was the last time we spoke to one another for 44 months until our happy reunion in Macau when I discovered to my great sorrow that my father had died on 4 December 1944, 8 months and 26 days before I was released from my Shamshuipo prison pen.

However, the turning off of taps meant that there was no water for flushing the toilets at H.Q. As hundreds were billeted at Victoria Mansions it is not difficult to visualize the mess and stench of overflowing toilet bowls. Relentlessly the ring of steel round the heroic defenders was closing tighter by the hour, the enemy by then having effectively broken the back of all resistance. Fighting was now sporadic and confined to isolated pockets of resistance along the fast contracting perimeter.

Winston Churchill signalled to the Governor of Hong Kong on 21 December: "...Every day that you are able to maintain your resistance you and your men can win lasting honour which we are sure will be your due". The great wartime leader subsequently in his six-tome history The Second World War, referring to the orders conveyed in that historic telegram confirmed that "those orders had been obeyed in spirit and to the letter". The Colony had fought a good fight. They had won indeed "the lasting glory".

The Prime Minister of Canada, Mr Mackenzie King, sent this message of encouragement to his countrymen who were fighting alongside the men of the Hong Kong garrison: "all Canada has been following hour by hour the progress of events at Hong Kong. Our thoughts are of each and every one of you in your brave resistance of the forces that are seeking to destroy the world's freedom. Your bravery is an inspiration to us all. Our country's name and honour have never been more splendidly upheld."

However, flesh and bone could not hold out indefinitely against numerical advantage and crushing weight of metal. Hong Kong raised the white flag at 4.43 p.m. on 25 December 1941 on the orders of Major-General C.M. Maltby on the instructions of the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Young, in his capacity as Commander in Chief of all the Forces in Hong Kong. He signalled His Majesty's Government as follows: "Military and Naval commanders have now advised me that no effective resistance can be made. I am taking action in accordance with that advice".

It does not fall within the narrow rope of this mini account of the personal experiences of a private soldier to describe in detail the gallant deeds of such brave men as Col Stewart, DSO; Col Newnham, GC; Capt Douglas Ford, GC; Flt-Lt. Gray, GC; Capt Ansari, GC; Brig-Gen. Lawson and CSM John Osborn, who won the only posthumous VC of the war.

By the same token it also does not fall within the ambit of this narrative to revive the blood-curdling massacres perpetrated by the Japanese during the frenzy of warfare at the Salesian Mission, near Shaukiwan; The Ridge, between Wong Nei Chung Gap and Repulse Bay; Eucliffe Castle, Repulse Bay and finally St. Stephen's College, all of which are well documented.

It would be presumptuous of me to tell you how it came about that the Winnipeg Grenadiers and the Royal Rifles of Canada were posted to this part of the world at a crucial moment of Hong Kong's history, neither would it be necessary for me to supply you with the figures of Canadian casualties suffered during the siege and, thereafter, during internment here and in other Japanese slave camps. Official Volunteer casualtiesThese figures speak for themselves of the part played by the Volunteers in the defence of Hong Kong. They are approximately 10% of the total. According to the authoritative list compiled for later editions of Colonel Evan Stewart's Hong Kong Volunteers in battle, based on the post-war report of Major-General C.M. Maltby, General Officer Commanding British Troops in China, 2,114 Allied army and 59 naval personnel were killed or listed as missing, and 2,359 were wounded in the eighteen day battle for Hong Kong. Another 2,340 died in POW and internment camps, have been put at: 210 killed; missing in action 22 and wounded 111.

With the cessation of hostilities on 25 December 1941, the Volunteers, as a unit, were ordered to move to Kennedy Road in the mid-levels where they temporarily occupied quarters which in peace time had housed married troops and their families. The story gained credence that it would be in the best interest of the Volunteers to stick together because of back pay due them and other benefits such as payment of compensation due to loss of property caused by acts of war, loss of furniture due to looters and compensation for vehicles commandeered at the outbreak of hostilities by the civilian authorities for their use. As things turned out Volunteers received not a cent in compensation from an uncaring government.

But the story that gained the widest currency and acceptance was that the Japanese would disband the Volunteers as a unit, because they were civilian part-time soldiers as opposed to the mercenary, fulltime professional type of soldiery. The Japanese interpretation, however, was short and incisive: (a) they were not signatories to the Geneva Convention and (b) the Volunteers took up arms against the Japanese and killed hundreds of their troops during the fighting and were, therefore, in their eyes to be regarded as enemies like their professional counterparts. That put an end to any hopes of a disbandment.

On 30 December the Volunteers were ordered to parade at around 10 a.m. on the sacrosanct turf of the Hongkong Cricket Club, where in palmier days the class-conscious taipans of the various prestigious 'Hongs' indulged in that national obsession called cricket, the epitome of a gentleman's game. After cooling our heels around for some time a convoy of trucks arrived at the scene and disgorged dozens of booted Japanese NCOs and privates, the former trailing behind them oversized samurai swords, the privates carrying rifles.

The parade was called to attention and the privates began the business of counting heads as they passed up and down the ranks of Volunteers. It took some time before the Japanese got their sums right. We were then forthwith marched to Queen's Pier, where in post-war days VIPs visiting Hong Kong, such as royalty and heads of state, landed on terra firma from the Governor's launch, Lady Maurine. We piled into a Star Ferry launch moored alongside the pier and landed in Kowloon ten minutes later, still ignorant as to where our new home might be for an indefinite future that lay ahead of us. The records show that 1,759 Volunteer loyal subjects of the King answered the clarion call when bombs rained down on Kai Tak on 8 December 1941 in a Japanese sneak attack.

Allowing for war casualties and those who, upon capitulation had discarded their uniforms and melted unobtrusively away into civilian life, I estimate that roughly 800 were on parade'Operations in Hong Kong from 8th to 25th December 1941', Supplement to the London Gazette, 29 January 1948, p. 725. at the Hongkong Cricket Club's sacred turf' and eventually made the ferry trip to Kowloon for the painful march which ended at Shamshuipo POW Camp at 4 p.m. on 30 December 1941.

I shall attempt to recreate in words the scene that unfolded along the via dolorosa that Nathan Road turned out to be to the 800 Volunteers who trudged wearily along it some 46 years ago.

Nathan Road is Kowloon's widest, longest and most beautiful thoroughfare. It was lined on either side by venerable, shady banyan trees which met overhead to make it an arboreal avenue. On that sad afternoon it was crowded with curious onlookers, among whom were the relatives, wives and sweethearts and friends of the Volunteers. There are today left but 53 ex-PoWs, who can recall that afternoon of ignominy which, ironically, was enacted in their own home town. The men were shouted at, those who could not keep up with the rest of the marchers, and generally treated like so many insensate heads of cattle rather than as dignified human beings by the haughty soldiery, still drunk from the heady intoxication of victory over a white race it had for long secretly harboured hatred against.

Little did the dejected men suspect then that once those tall forbidding iron gates clanged to for most of them Shamshuipo would be their captive microcosmic world for a seeming eternity, whether they liked it or not. The 800 bedraggled Volunteers joined the 7,000 or so troops who had preceded them into abject captivity by a couple of days.

If ever there was a winter of discontent it was that first one behind barbed wire at Shamshuipo. As luck would have it, that winter was one of the severest in many years.

Shamshuipo had served as a former barracks by the British Army. When the troops evacuated Kowloon on the 11 December to avoid entrapment and annihilation by the Japanese, looters took away all the woodwork of the barracks as it fetched a lot of money in a thriving black market for firewood. It had become indispensable because the two electricity generating plants, one belonging to the China Light and Power Co. in Kowloon and the other to the Hong Kong Electric Co. in Hong Kong were both out of commission.

It broke the hearts of the Volunteers when they found out that the Nissen huts, to which they had been assigned were devoid of window frames and doors by the looters. They had to sleep on the cold unfriendly concrete floor in the soiled clothing they wore when they marched into captivity, as army-type iron-framed beds were then unavailable. Many had to share a single army horse blanket between two for extra warmth. The cold piercing north winds whistled unimpeded through windowless and doorless huts for the remaining long wintry months that lay ahead.

How I envied those who could sleep uninterruptedly throughout the long hours of the night without ever having to visit the latrine situated a good distance from the men's quarters near the electrified barbed wired perimeter, patrolled day and night by armed guards and fierce Alsatian dogs with strict orders to shoot to kill anyone attempting to escape. The men had all been instructed to shout out aloud "Banjo", latrine in Japanese, when one needed to answer nature's call to avoid the risk of being shot at. Because of a weak bladder, I had to make the hazardous trip more than the others. I am convinced that after some time all the perimeter sentries came to recognise my stentorian voice.

The Japanese were only too pleased to allow our people to run Shamshuipo PoW Camp for them. They, however, showed a remarkable degree of insight into human character when they appointed Major Cecil Boon, RASC, to head the camp's administrative office which was staffed by five Portuguese volunteers, who did all the clerical work. Boon did not disappoint his alien masters for he proved to be most compliant to their every wish. He became the man whom the PoWs most loved to hate. After the war he faced a general court-martial in England on eleven charges, one of which was assisting the enemy. The trial aroused worldwide interest and took place in London in 1946.

Boon engaged the top silk of the day to defend him. Under severe cross examination by defence counsel many of the prosecution witnesses wilted and their evidence was marred by contradictions and discrepancies due to faulty memories. In compliance with a cardinal principle enshrined in British justice the defendant was given the benefit of doubt and, accordingly, acquitted. Legal costs were said to have ruined Boon financially.

The job allotted to the Field Ambulance soon after arrival at Shamshuipo could not have been more menial nor more malodorous under the sun: (a) cleaning latrines and (b) drainage of sewers. I took my turn by rotation as a member of an eight-man fatigue party after the morning parade to collect all the buckets of excreta from the various latrines, then loading them on to a truck, jocularly referred to as 'the honey wagon' and then trundling it to a pier, from which the men had to descend a flight of steps to reach sea level and, from there, empty the buckets into the briny and then rinsing the buckets with salt water before returning them to where they belonged.

A less demeaning and unpleasant task was that of ensuring that the camp drainage system did not clog up and so give rise to pools of stagnant water which would provide the ideal places for the malarial-propagating Anopheles mosquitoes to breed.

It took the Japanese some time to get fully organized. During that critical interim many Volunteers, mostly local boys, comprising Eurasians, Indians, Portuguese and Chinese took full advantage of a break in the wire fence at one sector of the perimeter to make good their escape from prison life under the Japanese. The most successful ruse exploited by the escapees was to wear an oversized army greatcoat over their civilian clothes. They would be at the advantage in the fading evening light. When the sentry reached a critical point of his measured pacing a trusted 'buddie' of the hopeful escapee would give a prearranged hand signal, whereupon the latter would hurriedly discard the great coat and walk briskly across a narrow street opposite the fence and be swallowed up by the friendly dimness of the verandah of an adjacent block of building parallel to the fence and disappear from sight to freedom.

There were several escapes from Shamshuipo Camp, but the most notable of the early ones was that of January 1942 when Lt-Col L. T. Ride, Lt. D.F. Davies, Lt. D. W. Morley and Pte Lee Yan Piu, Ride's clerk at the Hong Kong University, made their successful bid for freedom. Ride eventually made his way to Chungking, from where he broadcast to the world the first news of Japanese atrocious treatment of PoWs, the lack of drugs and medicines and the deliberate starvation diet fed PoWs by the Japanese, ending by predicting dire consequences for the captives. He was promoted to full colonel and awarded an OBE for his exploit.

After a couple of months behind barbed wire, to help while away the tedium of camp existence, permission was granted to hold open air band concerts once a week on Saturday afternoons by the massed brass bands of the various regiments in Shamshuipo. The band on these occasions rendered a pot-pourri of old favourite tunes much to the delight of the men who, for at least a couple of hours, could forget about their miseries. It invariably ended with the national anthem with the men standing stiffly to attention. This display of patriotism was frowned upon by the camp authorities and an order was instantly issued forbidding the playing of God Save the King at the end of a concert. Not be outwitted, the bandmaster had the brilliant idea playing at the next al fresco concert that quasi-national anthem substitute, Land of Hope and Glory, which was perfectly acceptable to our captors.

Mindful of the fact that idleness teaches much mischief, the Japanese emptied the bookshelves of many private libraries around Kowloon and carted truckloads of books back to Shamshuipo to start a library in the first six months of 1942. Mr Gerald Goodban, an Oxford English scholar and Headmaster of the Diocesan Boys' School, became the first camp librarian. He made his daily round to the hospital wards to take down a list of what books hospital inmates would like to read. The library helped a great deal towards sustaining and preventing the morale of the men from slipping further down through those long, depressing months of waiting, waiting for the end that was promised, but never seemed to come. An avid reader myself, I sought forgetfulness of my sad lot by reading a wide range of books, but I took particular delight in reading every book I could lay my hands on by that peerless master of light-hearted humour, P. G. Woodhouse. I stopped visiting the library only upon medical advice when my eyes started weeping and losing their acuity.

While PoWs were supplying the slave labour to extend the runway at Kai Tak in the summer of 1942 they were woken every morning at the ungodly hour of 6 a.m. in order to allow sufficient time for them to finish their matutinalmorning ablutions, have their frugal breakfast and yet have the time to make the 7 a.m. ferry which would take them to their site of hard labour.

It was during one of these working parties that an American fighter aircraft, based in Free China, suddenly appeared from behind the sun and swooped down with machine guns blazing, disappearing into the safety of Free China as suddenly as it had appeared. It was a nuisance raid in the autumn of 1942, the first of many air raids before PoWs were ultimately freed from thraldom.

At the beginning PoWs marched from Shamshuipo camp to Kai Tak, but this soon became public knowledge and the wives, sweethearts and friends of PoWs lined themselves at strategic points along the set route of the march hoping to catch a fleeting glimpse of their imprisoned dear ones and, if possible, by hand signals convey some message of hope but this, when detected, annoyed the guards, sometimes with serious consequences to the culprits who were beaten before the eyes of the PoWs.

To obviate repetition of such breaches of security in future, it was decided to ferry PoWs to Kai Tak, where they had to level a hillock with pick and shovel to provide earth and rock with which to extend the runway for military use. PoWs were rewarded with a few biscuits and a packet of Japanese cigarettes at the end of a hard day's labour. The exhausting work lasted many months and, no doubt, hastened the, deaths of many of the men whose health was progressively deteriorating due to vitamin deficiency diseases.

After boarding the ferry there was a rush for the most comfortable nooks so that whoever got them could enjoy a revivifying forty winks before doing the back-breaking work at Kai Tak.

I noticed one chappie always carrying a huge tome in his haversack. Intrigued, one day I asked him if he minded showing me the book. It was an anthology of the works of some of the great Greek thinkers of classical antiquity. I was suitably impressed by the man's lofty taste for literature and asked him which of the philosophers he admired most. The deflation came swiftly: "I don't care a damn what is between the covers of the book. It just happens to be the right height for a perfect pillow on which to rest for a short nap before I reach Kai Tak."

On the 11 April 1942 a party of four escaped from Shamshuipo Camp. They were Capt JD Clague, Clague commanded the British Army Aid Group in Huizhou. He was knighed in 1971. Lt LS White, Lt JLC Pearce (all three Gunners) and Sgt DI Bosanquet, AA Unit, HKVDC. As soon as the camp authorities got wind of the escape, the camp was rudely awakened in the wee hours of the morning by the camp bugler sounding a peremptory 'muster at the double' at the parade ground. Those who were lucky to have the luxury of waterproofed ground sheets were adequately protected from the pelting rain which came down that night in buckets, but a lot of the men, myself included, were drenched to the skin, feeling miserable throughout the marathon parade.

For punishment we stood around for something like four hours shivering in the rain during that unforgettable night, while the ill-tempered sentries with flashing torchlights in hand started the laborious task of counting heads and then checking the results with Camp Office figures to determine exactly how many had got away. Because the escape had involved three officers and a sergeant, the Japanese felt they had lost much face and took the severest collective reprisal ever against their charges. They banned food parcels from camp, which were vital in making up for the vitamin deficiency of camp diet. Furthermore, the camp authorities decreed the imposition of 100 days of plain rice for the two main meals of the day.

It was during this period of extreme deprivation that the twin outbreaks of diphtheria and bacillary dysentery occurred. Hundreds of PoWs perished during the onslaught of these two epidemics due to the absence of specific drugs to combat these diseases.

A word on food parcels will not come amiss at this juncture. Food parcel days were red letter days in camp for the local PoWs and to some of the imperial troops who were stationed here before the war started and had time to establish liaison with Chinese girls. After the morning parade, those who expected parcels made a beeline for the most advantageous spots along the barbed wire fence where they could see and be seen by their relatives, wives, sweethearts and friends from as close range as possible.

The PoWs and parcel bearers wore the same bizarre attire and head-gear on parcel days to ensure mutual instant identification. Any attempt on the part of parcel bearers to communicate with POWs by hand signalling was sometimes brutally put down by the sentries responsible for orderly behaviour by rough and ready summary corporal punishment meted out before the eyes of the PoWs at the fence. There is no telling how many owe their survival through the timely arrival of those life-saving food parcels.

My younger doctor brother Germano had the bright idea of lacing bottled home-made sambalsspicy Indonesian sauce with a generous sprinkling of vitamin tablets of different kinds which fortunately for me had eluded the eagle eyes of the parcel scrutineers. After several months of supplementing my meagre camp diet my brother left Hong Kong to join the Ribeiro clan in Macau. There were a few more escapes from camp after that of April 1942, but for reasons of space I shall bypass all of them.

I told you earlier on why Shamshuipo Camp was plunged in darkness in the evenings. Electricity, however, was restored on March 10, 1942 to a spontaneous outburst of collective jubilation that rang from one end of the camp to the other. The improvised oil lamps, smelly and smoky, but nevertheless indispensable, ended ingloriously in litter bins since they had outlived their usefulness in much the same way, alas, as ex-PoWs are now being callously ignored and treated shabbily by a government with a conveniently short memory.

The precious oil for the lamps had been scrounged by smart operators with an eye to the main chance from the oil sumps of several derelict military trucks which had been written off the books by the army.

By this time, tired of being a manure collector, 1 applied for and obtained the more respectable job of doctor's clerk. My duties were to help the MOMedical Officer with paper work at morning sick parades and to keep medical records up to date.

The harsh imposition of the rice only policy by way of collective reprisal in the aftermath of the officers' group escape from Jubilee Building was beginning to manifest itself by May 1942 when long queues formed daily outside the MO's office. They became thereafter a familiar daily sight.

About this time I developed a spot on my head, reminiscent of a monk's tonsure. I showed it to my MO, Captain Balean, and he diagnosed it as alopecia areata. He found it of academic interest as it was the first case he had come across in camp. I continued to clerk for successive MOs as my health continued its downward slide from A, then to B and ultimately to C class, which saved me from being drafted to Japan, as the Japanese had no use for unproductive crocks.

I was at the time clerking for another MO who shall remain nameless. In the absence of the most basic medicines such as cough mixture, aspirins, etc., there was very little any doctor could do for the sick, except offer plenty of tea and sympathy. I recall a certain Volunteer at sick parade complaining of some malady to this MO and he just told the man; "Go to the tap and drink gallons of water. It will flush your system out and do you good".

Now water was the only commodity that was never lacking in camp for reasons which I shall let you know later. The MO could have offered the sick man some words of comfort. His wry wit was not only uncalled for but justifiably resented, I thought. For some unknown reason, the Japanese brought in iodine and mercurochrome in ample supplies. A certain Portuguese Volunteer, no Adonis by any stretch of the imagination, reported sick one morning. His face had broken out into a rash and the MO gave him a chit to go to the infirmary, where the orderly dabbed his face with one of the two camp panaceas, mercurochrome, which accentuated its ugliness. The moment our man entered the hut one wag remarked loudly: "Say, what has happened to your arse?". The whole hut erupted in an explosion of uncontrolled uproarious laughter.

At the outbreak of war the population of Hong Kong was roughly a million and a half souls. Due to the growing scarcity of food, the Japanese embarked on a policy of depopulating Hong Kong because they were not prepared to feed hundreds of thousands of unwanted mouths. We could see the practical implementation of this draconian policy from the camp as tens of thousands of Chinese under Japanese armed escort in the early months of the occupation snaked their way up Shatin Road on their way to being deported to China. By February 1943 Japanese census put the population figure at 968,524. This substantial reduction in the population was the major reason why Shamshuipo Camp had a round- the- clock supply of potable water.

Due to the starvation diet, vitamin deficiency diseases began to manifest themselves, the most common being beri-beri, pellagra, tacchy cardia and a variety of skin diseases, such as scabies. A much dreaded affliction was a form of neuritis, aptly dubbed by the men as 'electric' feet and hands. It made sleep impossible because of the constant shooting pains.

The poor victims paced endlessly at night outside their huts wrapped up in horse blankets against the Arctic blasts until utter physical exhaustion took over and mercifully provided them with the hoped for anodyne which brought on a fitful sort of sleep and a temporary welcome relief from agonising pain. The victims invariably lost all sense of feeling at the extremities of their limbs and did not react to pin pricks either on their soles or palms.

I was told of a pathetic case in which a patient in one of the hospital wards suffering from this painful affliction asked the orderly for a basin of hot water, but was mistakenly given boiling water. Unwittingly, the poor man immersed his tortured feet into the basin of water only to discover, but too late, to his horror that the water he had been given was boiling on noting that the skin of both feet was peeling off.

Optical atrophy was another disease which ruined the promising careers of many a young man who had survived the horrors of Shamshuipo PoW Camp, for which the medical term is, I believe, retrobulbar neuritis. Diphtheria and bacillary dysentery were the two epidemics which broke out around September and October 1942 to which hundreds in camp succumbed.

The Japanese took no action to contain or combat the twin killers until at least 100 had perished before an inadequate supply of antitoxin was brought into camp. This left the MOs in camp with no option but to have to play the role of God. Those of their patients who were too far gone were reluctantly allowed to die, while the precious serum was reserved for the ones who had just contracted the disease and had better chances of being cured on a minimum dosage of the serum.

I think the onset of dysentery came around October 1942. Reports circulated in camp that in the dysentery wards some of the patients died of dehydration or from sheer physical exhaustion while seated on bed pans. If only an adequate supply of the sulpha wonder drug, referred to commonly at the time as M & B tablets, had been available, a large percentage of the fatalities could have been avoided.

Whenever a death occurred in camp, out of respect for the deceased, the camp authorities in the early days had no objection to the camp bugler sounding the doleful Last Post. When the twin epidemics were at their most virulent, the repeated sounding by the bugler of this mournful soldier's last tribute was heard day in and day out and this had a most depressing effect on camp morale. The last straw happened one day when this last homage to a departed soldier was heard no fewer than thirteen times. I well remember keeping a mental tally on that depressing day. Camp orders were immediately given that forthwith the practice of the bugler sounding the Last Post when a death occurred in camp would cease. In the first year of internment 352 men died of various diseases, caused mainly by vitamin deficiency in the diet. Average loss of weight was between 40 and 50 pounds, but cases in excess of these figures were not uncommon.

I knew a Volunteer who weighed 250 pounds when he was fighting fit before he entered camp. He was a keen sailor and delighted in recounting the following story against himself. He said that his weight came in very useful when he went boating as it could always be used as ballast. The starvation diet, however, soon trimmed him down to a svelte 110 pounds. The distended folds of yards of flabby skin, once stretched tight like that of a drum over his protruding tummy, now draped unsightedly over it in multiple layers like the wrinkles of China's fighting shapei dog.

Shamshuipo PoW Camp, too, had its fair share of walking skeletons, only they did not get the glare of publicity which those in such notorious Nazi concentration camps at Auschwitz, Belsen and Treblinka did. According to the Red Cross Geneva Convention, PoWs were supposed to be fed food containing 2,400 calories per man per day, but at camp over a three month period averaged a disgraceful 380 calories per man per day only.

Another privilege that was soon taken away from PoWs was that of sending letters and receiving them from one's near and dear ones. It undoubtedly was a morale booster, while it lasted. Letters had to be written on Japanese issued post cards and they were restricted to 25 words, address included. The topic had to be non-political and confined to the purely personal, so when it was mail day in camp everybody had to put on his thinking cap to string words together which would convey exactly what one wanted to say as economically as possible. My post cards to my family in Macau were always put under the family microscope to see if they revealed any tell-tale evidence that my sanity was wavering. Like the band concerts and 'food parcels day', the privilege of letter writing also got the axe.

From this time distance I cannot pinpoint the date when the Japanese began accepting money for payment to PoWs through the aegis of the International Red Cross in Macau, but my guess is that it started in mid 1942 or thereabouts. Like the other privileges referred to, the inward remittances were also abruptly cancelled without giving any explanation.

Concerning Red Cross remittances, yet another Good Samaritan came to my rescue in the person of Mr JM Pitter, whom I had befriended in 1920, when we were boarders at St Joseph's College, Macau, run by Portuguese secular priests. I was then a lad of 12 years and had been sent to Macau by my parents to learn the mother tongue.

I was pleasantly surprised when out of the blue I was summoned to collect a remittance of Military Yen 50 and subsequently discovered that it was from my old school mate. As the conquering power, the Japanese had imposed the military yen on the people of Hong Kong as the only official currency and arbitrarily fixed it at HK$5.00 = M. Yen 1.00 because Japan desperately needed foreign exchange to sustain its tottering war effort. The windfall was God-sent because I was showing the first symptoms of optical atrophy. My vision was beginning to blur and my eyes started weeping. I reported my condition to my MO and he counselled me to stop reading as he knew I was an avid reader. I was recommended to buy fresh duck eggs and cod liver oil, if these were available, at the Japanese-run canteen. Again, luckily for me, these items were on sale and the money my good friend spent on me came in very handy indeed.

To derive the maximum benefit from the duck eggs I broke a raw egg every time over my hot rice and religiously took a spoonful of cod liver oil. Raw duck eggs have a very strong fishy tang. As long as the remittances kept coming and the canteen remained open, I invested my money on these two nourishing items of food. Alas, both were short-lived, but, thank God, long enough to enable my sight to overcome the incipient onset of eye atrophy.

A few paragraphs back I mentioned how letters received from one's near and dear ones had uplifted the waning spirits of the men. The 230 or so Portuguese in camp were 100 per cent Catholics. They had behaved just like a flock of lost sheep, until Father Green, an R.C. Chaplain, arrived on the scene around April 1942 to minister to their spiritual needs. He had to badger the Japanese authorities for months on end and it was widely believed at the time that he finally succeeded in his desire to gain admission into camp through the influential intervention of the then Italian R.C. Bishop Valtorta, bearing in mind that Italy was a member of the recently concluded Tripartite PactAn agreement between Germany, Italy and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940, of which Japan was the junior partner of the Axis.

The first day Fr Green was integrated into the camp long queues formed outside his hut for confession, some of the men not having confessed for donkey's years. With the kind co-operation of the R.E.Royal Engineers and many willing pairs of hands an empty hut was quickly transformed into a chapel, where the faithful could attend daily Mass and receive Holy Communion and seek spiritual solace and counsel, if and when needed, from an understanding pastor. There was no shortage of acolytes and volunteers to keep the chapel always shipshape and Bristol fashion.

The moment Fr Green came to camp the morale of the Catholics rose noticeably. The lads had at last found the moral crutch they needed. It cannot be evaluated to what extent the reassuring presence of the good padre was responsible for contributing to the low mortality of the Catholics in camp. His presence in the hospital wards was always welcomed by members of his flock to whom he always had words of comfort to say. And because Fr Green was a man of moral rectitude his ministry resulted in a number of conversions. I know of at least two, one an Armenian, the other a Christian, of whose conversion and tragic story I shall relate hereunder.

Mr RS Harrison was my immediate superior in 1936 when he took over the Foreign Exchange Department of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. He was always kind and fair in his dealings with the staff, which was then 100 per cent Portuguese.

At that time an unfortunate clash of tempers between Harrison and the senior member of the local staff led to the summary dismissal of the latter. As an eye witness to the unpleasant incident I must, in all fairness to Mr Harrison, say that the dismissal was fully justified without, however, wishing to delve into the circumstances.

At the time of the rumpus I had only five years' service and would have been adjudged too junior to take over such a senior and responsible desk. Mr Harrison, realizing the situation, spoke to me privately. He said that if I could balance the books that evening, which would be in my best interest, he would strongly recommend me for the vacancy. I replied that it would be a tall order, but that I accepted the challenge. I stayed behind that evening, and, miracle of miracles, alone and unaided, I achieved an unheard of spot balance.

The next morning when Mr Harrison arrived at the department he knew that I had not let him down, judging from the broad grin on my face. The balanced books satisfied my boss that I was capable of taking over the job. He strongly backed my candidature with the powers that be and against the opposition of the old guard I was made senior local officer of the Foreign Exchange Department over the heads of many senior to me in service, ruffling many feathers in the process. Come the Pacific War, fate threw Harrison, my former boss, and me together as prisoners of war in Shamshuipo PoW Camp, me a private in the Field Ambulance and he a Sub -Lieutenant in the "Wavy Navy"The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), which was commonly called the "Wavy Navy", after the 3/8-inch wavy sleeve 'rings' that RNVR officers wore to differentiate them from Royal Navy officers.

Harrison was a keen chess player and so was Pte CL Lopes, who was an old friend of mine and also a departmental colleague and had therefore worked under Harrison. The two were often seen together in the Portuguese hut pondering over what would be the next decisive move on the chess board. The game of chess was in camp ideal for solving the perennial problem of ennui. Thus these two men were brought closer together to one another than would have been the case in peacetime conditions, when they probably would have moved socially worlds apart. Similarly infatuated with the game of chess was Fr Green. It would not be unreasonable to suppose that the fondness of this intellectually challenging game could have brought padre and Harrison together often in the privacy of the chaplain's quarters.

Shamshuipo Camp was a place where many, who had never before given a moment's thought to religion in the hurly burly of the rat race before the war, began to take stock of their sometimes misspent lives during those long lonely hours of solitude during their enforced camp stay. This, I think, was what might have happened to a serious minded man like Harrison, when he surprised his chess opponent Pte Lopes one day by asking him point blank to stand as his baptismal godfather, having made up his mind to embrace Catholicism.

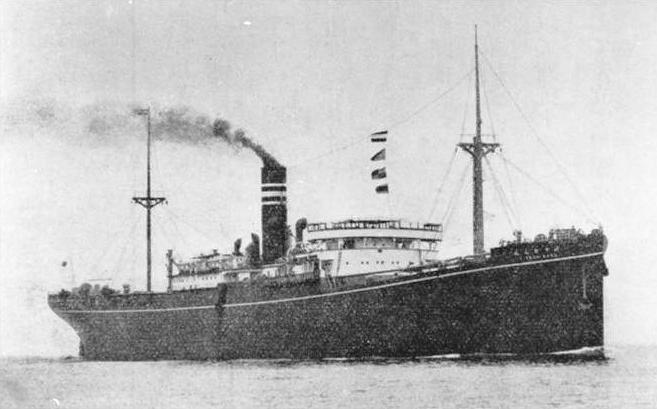

When the Japanese prepared the draft list of PoWs who were to leave on the ill-fated Lisbon Maru on 27 September 1942, Sub-Lieut Harrison found himself included in the list of 1,816 draftees.

Harrison had gleefully produced from the depth of his kit bag a last precious tin of cocoa. He had decided he would blow it up in one frenzied orgy of self-indulgence on the eve of his departure to Japan with his hut mates, among whom he had included Pte Lopes, his friend chess rival and baptismal godfather. Unfortunately, in the course of the celebration Harrison overturned a kettle of boiling water on his sound leg. He had been born with a gammy leg and walked with a marked limp. The sound leg, unluckily, had been extensively scalded and Maj. Ashton-Rose, the camp's senior MO, told Harrison that he was in no condition to undertake the long and arduous sea journey to Japan under the most cramped condition imaginable and that he could easily take him off the draft by simply reporting him totally unfit for the voyage. Harrison's reply was typical of the man: "Maj. Ashton-Rose, I understand what you are saying and thank and appreciate your kind consideration for my well-being, but I am afraid I must decline your offer because it will only mean that another man will have to go in my place."

Rarely does one come across such unselfishness in man. Harrison left on the Lisbon Maru. He had to be carried on board on a stretcher and was among the unfortunate 1,092 who ended his life in a watery grave. The premonition of disaster which Harrison had harboured in his breast but left unsaid, turned into tragic reality. It had been the noble refusal of this morally courageous man to accept Maj Ashton-Rose's well-intentioned offer to have him taken off the draft at the eleventh hour that had enabled some unknown POW to be, hopefully, alive somewhere today.

As for Pte Lopes, sad to say, he left Shamshuipo Camp with both eyes irreparably damaged by retrobulbar neuritis. Soon after the war he appeared before a medical board which assessed his eye impairment at 85% and awarded him a pittance in disability pension. His physical disability ruined an otherwise potentially brilliant career at the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank. He and his wife have been living in the outskirts of San Francisco for several years now. Lopes has been for several years an inmate of a privately run hospital for the aged. He requires round- the- clock nursing. In the summer of 1985 my wife and I visited our old friend Lopes in the above-mentioned hospital and the pathetic state in which we found him broke our hearts. I believe that as a result of thyroid dysfunction he developed a series of complications with the result that now he virtually lives in a semi-comatose limbo of oblivion. He showed no signs of recognising the people around him and has lost track of time. The genesis of all his woes, no doubt, could be traced back to the extreme rigours of camp life under the Japanese for 44 months.

I apologize for the need to turn the camp clock back to the time when the Pope reportedly sent $10,000.00 to the camp for the purpose of buying sporting gear for the men. Fr Green had reason to believe that the camp authorities had not spent all the money received from His Holiness. He had the brazen audacity of going to the Japanese to ask for an explanation in connection with the disbursement of the Vatican funds. For his impudence, Fr Green was given such a battering that he passed out completely and had to be revived by throwing water over his face.

Here we have a shining example of how camp life can bring out the best in man, while at the other end of the human scale we had in camp despicable characters, who became trader horns, loan sharks and, the lowest of the lowest, Japanese stool pigeons, who ratted on their comrades for a few packets of cigarettes, because they did not have the guts to give up smoking.

A week after the escape of Capt Clague and his party from Shamshuipo on 11 April 1942 the Japanese transferred the bulk of the Officers' Corps to another camp situated at Argyle Street.

I shall never forget that date because it happened to fall on my 33rd birthday and I was one of the 'coolies' detailed to lug the officers' belongings to their new home.

As far as I can recall there had been in all between six and seven drafts to Japan from Shamshuipo Camp. It was pretty obvious that the Japanese were feeling an acute shortage of manpower and were forced to siphon off men from PoW camps in Hong Kong to make up for the short-fall. The first draft sailed from Hong Kong on 3 September 1942 for Japan. The second left Hong Kong on 27 September 1942. It was the ill-fated Lisbon Maru draft.Luigi Ribeiro's original manuscript included this refeence to a newspaper cutting which was not present with the copy used for this manuscript. The steamer was torpedoed on 1 October 1942 by an American submarine, the USS Grouper, with heavy loss of lives.

A South China Morning Post reporter, Barry Grindrod gave a graphic account of this incident, in that paper's Saturday Review on 13 December 1986. Grindrod's interviewee was a Mr Andrew Salmon, who was one of the lucky survivors of this appalling marine tragedy.

In the telling of his story, however, Mr Salmon made one factual slip-up which prompted me to write to the South China Morning Post in order to set the records straight. The following is a gist of what I wrote to the newspaper in rebuttal of Mr Salmon's assertion that Portuguese Volunteers in camp had also been freed with their Chinese counterparts. On the 8 September 1942 the Japanese saw fit to release some 60 Chinese Volunteers from Shamshuipo Camp. In news-starved Shamshuipo this extraordinary event immediately sparked off strong rumours that the Portuguese, being third nationals in the eyes of the Japanese, would be the next in line also to be freed.

This wishful thinking was given added plausibility by yet another rumour which had it that the Roman Catholic Italian Bishop Valtorta of Hong Kong was negotiating with the Japanese for the release of his captive Lusitanian flock. Sadly, those rumours proved utterly unfounded.

At about that time the Japanese propaganda mill launched the South East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere campaign with the obvious aim of currying favour with the many different races whose countries by then had come under the repressive heels of the all-conquering Japanese hordes. The setting free of a handful of Chinese PoWs chimed in perfectly with that grand propaganda ploy and much fuss at the time was made of it by the local puppet press.

Mr Salmon recounts the bestial behaviour of interpreter Niimori Genichiro towards PoWs. This sadist narrowly escaped the noose, but was sentenced to life imprisonment as his just desserts.

Another inhumane interpreter, the bane of the lives of Shamshuipoans, was Sergeant Inouye, dubbed Slap Happy, because of his predilection for this form of corporal punishment. He was born in British Columbia and was tried for a number of murders by a War Crimes Court set up in Hong Kong after the war. He was found guilty of the charges and hanged at Stanley Gaol in August 1947.