One man's covert war mission changed Hong Kong history

In August 1945 Roger Lobo - later a Hong Kong lawmaker - carried from Macau official confirmation war was over, allowing Britain to re-establish its rule and forestall a Chinese takeover

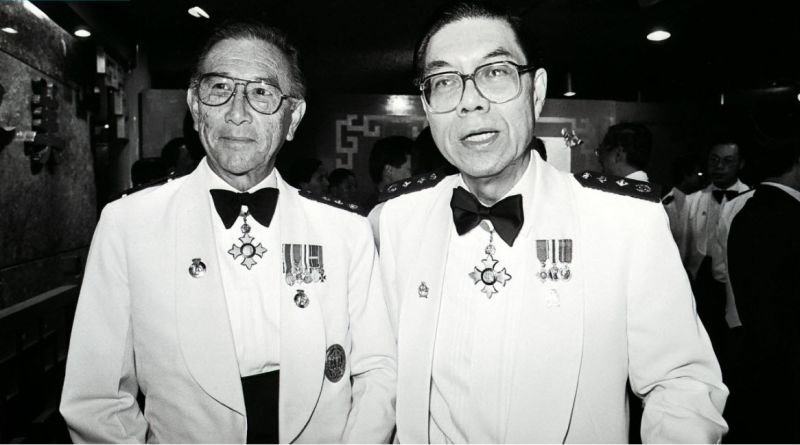

Sir Roger Lobo (left) with retiring director of health Dr Thong Kah-Eong, in 1988. Photo: SCMP

|

With the death in April of Sir Roger LoboClick on the SEARCH icon and enter his ID number (22200) to be taken to his personal page, 91, another vital link to the wider story of Hong Kong's Pacific war years passed into history. Seventy years ago last week, Lobo's brave actions significantly helped change the course of events in Hong Kong. A modest man with an extraordinarily distinguished record of public service that continued until his death, Lobo seldom mentioned his end-of-war exploit; like his equally remarkable father, legendary Macau business figure Dr Pedro Jose Lobo, Roger simply got on with what needed to be done in the public interest, effectively and without fuss. Early August 1945 was a tense time. It was obvious that the Japanese had lost the war, but a time frame for their surrender was deeply uncertain. It was by no means guaranteed that Japanese troops in the field actually would surrender to Allied forces, even if ordered to do so by the authorities in Japan. From Burma to the Pacific, the Japanese reputation for fighting to the death was thoroughly well-deserved; horrific experiences in Okinawa and Saipan, where the civilian population threw themselves off cliffs rather than surrender to the Americans, indicated what an Allied invasion of the Japanese home islands might look like. In the days that followed the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, action plans were made. In the case of Hong Kong, it was considered vital that the imprisoned colonial secretary, Franklin Gimson, should be sworn in as the acting governor, and reactivate the formal machinery of the British administration, as soon as a Japanese capitulation had been confirmed. This strategy was designed to ensure that Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists did not get to Hong Kong first. In the event, they made no attempt to do so. That it took senior Nationalist commanders - only a couple of hours away by air - more than a fortnight not to arrive, is a story that still awaits thorough examination. |

Vila Verde was the Macau holiday home of Dr. P. J. Lobo. Photo: Branca Gibbons/Orlando Lobo

|

|

British rule in Hong Kong was swiftly re-established due to a small group of individuals in neutral Macau who - at great personal risk - brought across formal confirmation from London that the war was over. Logistics for the mission to bring Gimson the written authorisation to take charge were privately entrusted to Pedro Jose Lobo. He had walked a diplomatic tightrope throughout the war, and his private radio station, Radio Vila Verde, which operated from his holiday home of the same name in the northern part of the city, was a vital Allied communications conduit. Roger personally carried the official document. |

|

In the unstable period immediately after the Japanese capitulation, when peace was fragile, two heavily armed fishing boats departed from Macau. The usual ploy for covert missions going in and out of the city was for one vessel to create a diversion to draw attention (and possibly enemy fire) while the other, more important craft passed undetected. Other fishing boats - manned with heavily armed, vehemently anti-Japanese pirates - escorted at a distance.

On arrival in Hong Kong, the document was delivered to Gimson via a third party, and the rest is history.

Macau's perennially shadowy business realities played their part in the mission's success. I once asked Sir Roger from where had the fishermen got their arms and ammunition? "Oh, my father's associates had their own contacts, I believe ." His voice trailed off, and we left it at that.

The full story has died with him.