O Ataque e a Derrota dos Holandeses em Macau, 24 de Junho de 1622

por by J. Bosco CorreaClick on the SEARCH icon and enter his ID number (38206) to be taken to his personal page1

Felipe III de Espanha (Felipe II de Portugal)

Clique para ampliar a imagem

Nos inícios do século XVII, Portugal tinha grandes vantagens no comércio com a China e com o Japão a partir de Macau, uma vantagem cobiçada pela Holanda. Na altura, Espanha e Portugal estavam unidas sob o reinado de Filipe III de Espanha (designado Filipe II de Portugal). Espanha e Holanda apresentavam uma longa história de conflitos, mas tinham assinado tréguas por 12 anos, de 1609 a 1621. Assim que o período de tréguas chegou ao fim, os Holandeses procuraram tomar Macau à força.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen, Governador-Geral das Colónias Holandesas na Ásia

Clique para ampliar a imagem

O Governador-Geral das Colónias Holandesas na Ásia, Jan Pieterzoon Coen, deu ordens para a invasão e enviou o seu comandante, Cornelis Reijersen, desde Batávia com uma frota de oito navios de guerra. A ele ir-se-iam juntar em Macau mais dois navios Holandeses e dois Ingleses, sob o comando de William Janszoon, destacados da frota Anglo-Holandesa, na altura a fazer o bloqueio ao porto de Manila, controlado por Espanha. A frota de Reijersen foi ainda reforçada por um outro navio Holandês e duas embarcações Portuguesas, capturadas ao largo de Malaca, e agora tripuladas por Holandeses, juntamente com alguns Japoneses2 que se aliaram aos Holandeses.

O esquadrão de quatro navios destacados da frota de Janszoon apareceu na rota de Macau, na manhã de 29 de Maio de 1622, na expectativa de interceptar, e de se apoderar, de navios mercadores Portugueses que eram esperados no dia seguinte, vindos da Índia e de vários portos das Índias Ocidentais, carregados de mercadoria preciosa. Porém, as suas tentativas foram em vão quando uma bem armada flotilha de lorchas foi enviada de Macau para escoltar estes mercadores em segurança até ao porto, através das ilhas.

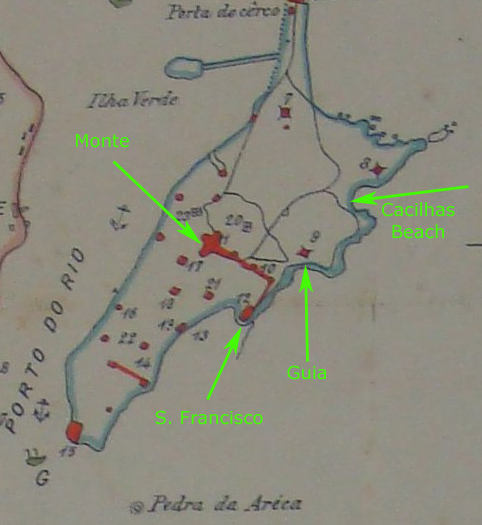

Mapa de Macau (1870) com referência aos locais abrangidos pela batalha

Clique para ampliar a imagem

No dia 23 - Vigília da Festa de São João Baptista - os Holandeses decidiram, após um reconhecimento, que a praia de Cacilhas seria o ponto de desembarque da operação a ter lugar no dia seguinte.

Para distrair as forças de defesa, Reijersen mandou três dos seus barcos atacar a bateria de São Francisco com um intenso bombardeamento, ao qual os Portuguese retaliaram com armas. Durante este duelo de artilharia, o qual durou quarto horas, os Holandeses bradaram às forças de defesa que o dia seguinte os viria mestres de Macau, e que as suas mulheres seriam desonradas após todos os homens terem sido mortos. Sendo óbvio que a invasão se daria no dia seguinte, Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho passou a noite a encontrar-se com os soldados e a exortá-los a lutarem até ao fim, uma vez que não poderiam esperar por misericórdia dos heréticos inimigos.

Na madrugada do dia da Festa a São João, 24 de Junho, dois barcos Holandeses deram continuidade ao bombardeamento da bateria de São Francisco, porém, desta vez, o contra-ataque Português teve mais sucesso, uma vez que um dos barcos inimigos foi destruído.

Entretanto, o ataque principal estava a ter lugar na Praia de Cacilhas, encoberto por fumo saído de um barril de pólvora humedecida, que fora acendida pelo inimigo, e por um intenso bombardeamento dos canhões dos navios, sendo o desembarque da força de assalto, composta por 600 soldados, auxiliada por 200 marinheiros armados.

A fazer frente a esta força de assalto, numa trincheira pouco profunda escavada na praia, estava uma força de cerca 60 soldados regulares Portugueses e mais ou menos 90 mosqueteiros Macaenses, sob o comando de António Rodrigues Cavalinho. No confronto que se seguiu, um tiro atingiu o Almirante Reijersen no estômago, levando-o a retirar-se para o seu navio-almirante. O Capitão Hans Ruffijn assumiu então o comando e persistiu no ataque. Com 600 homens a avançar em formação, Cavalinho e os seus homens foram forçados a recuar. Por esta altura, os Holandeses já tinham sofrido a perda de 40 homens.

Este confronto prosseguiu à medida que os mosqueteiros Portugueses iam recuando, até chegarem a uma fonte conhecida por Fonte da Solidão, localizada ao alcance da artilharia na cidade. Nesta fase, os invasores ficaram debaixo de um fogo intenso, proveniente dos canhões que haviam sido colocados pelos Jesuítas nos baluartes da incompleta fortaleza de São Paulo do Monte, onde, perante grande preocupação quando ao seu destino, as mulheres e crianças se tinham refugiado.

Um tiro foi bem disparado por um Jesuíta, Padre Jerónimo Rho, um famoso astrónomo, que acertou e rebentou com um vagão de pólvora no meio da formação Holandesa, com resultados devastadores. Do Monte, abriu-se fogo por meio de outras armas, causando ainda mais fatalidades entre os invasores.

Instalou-se o pânico, e temendo uma emboscada de um bambual próximo, os Holandeses pararam o seu avanço sobre a cidade e, vendo a ermida na Colina da Guia, com a sua altura dominante, dirigiram-se para ela. Contudo, o seu avanço pela colina foi confirmado por um grupo de trinta mosqueteiros e os seus escravos Africanos, comandados por Rodrigo Ferreira, todos bem escondidos atrás de pedregulhos. Abriram um intenso fogo sob os invasores, que não conseguiriam responder ao ataque sem se colocarem em risco.

Nesta altura, os comandantes Portugueses das fortalezas de São Tiago, à entrada do Porto Interior, e de São Francisco, ao aperceberem-se que o ataque estava centrado somente na Praia de Cacilhas, enviaram 50 Mosqueteiros sob o comando de João Soares Vivas, de modo a reforçar a principal força de defesa, comandada por Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho, que se estava a preparar para um contra-ataque decisivo.

Os reforços chegaram no momento crítico. Os Holandeses consideraram a sua posição insustentável: tinham perdido o depósito de pólvora; tinham-se confrontado com uma resistência inesperadamente forte; sofrido graves baixas, e estavam fatigados do constante conflito no calor do verão, além de que estavam em perigo de serem cercados. Como tal, decidiram retirar-se para os barcos antes que fosse demasiado tarde.

Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho aproveitou a oportunidade e ordenou um ataque, gritando "São Tiago e a eles!", um grito de guerra português. Os seus homens, ansiosos, não precisaram de mais encorajamento, e avançaram sobre os Holandeses. A eles rapidamente se juntaram os cidadãos Macaenses, os seus escravos Africanos, bem como Jesuítas armados e Frades.

Os Holandeses perderam a moral ao verem o seu comandante, o Capitão Ruffijn, atingido por um tiro. Aterrorizados pela furiosa ofensiva da defesa, particularmente dos escravos Africanos, que eram impiedosos e não davam tréguas, os Holandeses deram meia volta e retiraram-se em debandada, largando as suas armas e os estandartes. Na retaguarda também se estabeleceu o pânico e os marinheiros, preocupados que os seus escaleres se virassem pelos seus amedrontados camaradas, fizeram-se ao mar, deixando para trás as tropas à mercê do aço frio dos Portugueses e dos seus Africanos, ou à mercê de uma sepultura no mar.

Estimou-se que os Holandeses sofreram cerca de quinhentas baixas, incluindo a morte de dezoito oficiais. Um capitão e vários soldados foram feitos prisioneiros. Perderam todo o seu armamento, bandeiras, tambores e outro equipamento. Os vitoriosos recolheram mais de 1000 armas do campo de batalha. A defesa sofre a perda de quatro Portugueses, dois Espanhóis e vários escravos Africanos. Cerca de vinte ficaram feridos.

São João Baptista

Clique para ampliar a imagem

Em pouco mais de três horas neste fatídico dia, a poderosa força Holandesa foi totalmente derrotada por um pequeno, mas determinado grupo de Portugueses. No próprio campo de batalha, os vencedores libertaram os seus escravos Africanos, um sinal de reconhecimento da sua lealdade e bravura.

A população inteira esteve presente no Te Deum que teve lugar na Catedral, em agradecimento pela grande vitória, atribuída à intervenção de São João Baptista, a quem o dia era dedicado. São João foi declarado o Santo Patrono de Macau. Até aos dias de hoje, o dia 24 de Junho, Dia de São João, é celebrado em Macau com uma Missa especial na Sé Catedral, à qual assistem os dignatários locais

Conta a lenda que a rota escolhida pelos invasores Holandeses se deveu à aparição de São João Baptista, que, perante os surpreendidos Holandeses, trajava um manto que desviada todas as investidas inimigas.

Macaenses por todo o mundo têm tradicionalmente celebrado este dia em casa, usualmente com uma celebração farta, que no geral inclui sumptuosas sobremesas e uma grande variedade de frutas tropicais e exóticas. Diz a lenda que ninguém sofre depois de se deliciar com tal festim neste dia em particular, devido à protecção de São João.

Espera-se que, talvez, nós Macaenses, consigamos reavivar esta maravilhosa tradição e nos consigamos juntar onde quer que estejamos para comemorar o dia de festa do nosso Santo e celebrar, uma vez mais, a nossa heroica vitória de 1622!

1 Esta é a tradução, por Mariana Leitão Pereira, de uma versão editada a partir de um artigo que foi publicado no Boletim da Casa de Macau (Australia).

2 Charles R. Boxer mencionou que 20 Japoneses "..tinham vindo com a frota de Dom Juan da Silva desde Manila em 1621 com o objectivo de assistir os Portugueses em Macau face aos Holandeses; esta expedição atracou em Sião onde foi dominada e destruída numa desavença com os Siameses; estes Japoneses tinham escapado e agora pediam permissão para transferir para o Serviço Holandês". Alguns 12 ou 13 destes foram mortos na subsequente batalha em Macau [traduzido de CR Boxer, Estudos Para A História De Macau -- Seculos XVI à XVII, Fundação Oriente (Lisboa) 1991].

The Dutch Attack and Rout at Macau, 24 June 1622

by J. Bosco CorreaClick on the SEARCH icon and enter his ID number (38206) to be taken to his personal page1

Philip III of Spain (Philip II of Portugal)

Click to see full image

In the early part of the 17th Century, Portugal had a great advantage in trade with China and Japan through Macau that the Netherlands (Holland) coveted. At that time, Spain and Portugal were united under King Philip III of Spain (who was called Philip II of Portugal). Spain and the Netherlands had a long history of conflict, but had signed a truce for 12 years from 1609 to 1621. No sooner had that truce come to an end than the Dutch sought to take Macau by force.

The Governor-General of the Dutch Settlements in Asia, Jan Pieterzoon Coen, gave the order for the invasion and sent his commander, Cornelis Reijersen, from Batavia with a fleet of eight warships. He was to he joined in Macau by two Dutch and two English vessels that were detached from the Anglo-Dutch fleet under the command of William Janszoon, blockading the Spanish-held port of Manila. Reijersen's fleet was further strengthened by another Dutch ship and two Portuguese vessels that were captured off Malacca and now manned by Dutch crews, together with some Japanese2 who had joined the Hollanders.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen, Governor-General of the Dutch Settlements in Asia

Click to see full image

The squadron of four vessels detached from Janszoon's fleet appeared in the Macau roads on the morning of 29th May 1622, expecting to intercept and seize Portuguese merchant vessels that were due the next day from India and various East Indies ports, laden with valuable cargo. However, their attempt was foiled when a well-armed flotilla of lorchas was despatched from Macau to escort these merchantmen safely into the port through the islands.

Map of Macau (1870) showing sites involved in the battle

Click to see full image

On the 23rd - the Vigil of the Feast of São João Baptista (St John the Baptist) - the Dutch decided after a reconnoitre that Cacilhas Beach would be the point of disembarkation of their landing force on the following day.

To divert the defenders, Reijersen had three of his ships engage the São Francisco battery with heavy bombardment, which was answered by Portuguese guns. During this artillery duel, which lasted four hours, the Dutch shouted to the defenders that the next day would see them masters of Macau, and that their women would be defiled after all the men had been killed. As it was obvious the invasion would take place the next day, Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho spent all night visiting and exhorting the soldiers to fight to the last, as they could expect no mercy from the heretical foe.

At dawn on the feast day of São João, 24th of June, two Dutch ships resumed their bombardment of the bulwark of São Francisco but this time Portuguese counter-fire was more successful in that it destroyed one of the enemy ships.

In the meantime, the main attack was taking place at Cacilhas Beach, under cover of smoke from a barrel of damp gunpowder lit by the enemy and heavy cannonade from the ships, with the landing of the assault force of 600 troops supported by some 200 armed seamen.

Opposing them from a shallow trench dug on the beach was a force of some 60 Portuguese regulars and 90-odd Macaense musketeers, under the command of António Rodrigues Cavalinho. ln the ensuing clash, a shot hit Admiral Reijersen in the stomach, compelling him to retire to his flagship. Captain Hans Ruffijn then took over the command and pressed on with the attack. With 600 men marching in orderly formation he thrust Cavalinho and his men back. By that time the Dutch had already suffered the loss of 40 men.

This engagement continued as the Portuguese musketeers withdrew until they reached a spring called Fontinha, within artillery range of the city. At this stage the invaders came under fire from a heavy cannon which had been mounted by the Jesuits on the bulwark of the half-completed fortress of São Paulo de Monte and where, amidst great consternation as to their fate, the women and children had taken refuge.

A well-placed shot by the Jesuit, Padre Jeronimo Rho, a famous astronomer, blew up a wagonload of gunpowder in the midst of the Dutch formation, with devastating results. Other guns from Monte opened fire, causing further casualties among the invaders.

Panic set in and fearing an ambush from a nearby bamboo thicket, the Dutch halted their advance on the city, and sighting the hermitage on Guia Hill with its commanding height, wheeled towards it. However, their advance up the hill was checked by a group of thirty musketeers and their African slaves, led by Rodrigo Ferreira, who were well hidden behind large rocks. They opened harassing fire on the invaders, who could not return fire without putting themselves at risk.

By now the Portuguese commanders of the garrisons at São Tiago, at the entrance of the Inner Harbour and São Francisco, realising that the attack was confined solely to Cacilhas Beach, despatched 50 Musketeers under the command of João Soares Vivas, to reinforce the main defenders, led by Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho, who were preparing for a decisive counter-attack.

They arrived just at the critical moment. The Dutch considered their position untenable: they had lost their powder store; they had found resistance to be unexpectedly strong, had suffered heavy casualties and were fatigued by constant skirmishing in the summer heat, and were in danger of being encircled. So they decided to retreat to the ships before it was too late.

Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho seized this opportunity and gave the order for attack, shouting the Portuguese battle-cry of "São Tiao" - "St James and at them!". His eager men needed no urging and hurled themselves at the Dutch. They were soon joined by Macaense citizens, their African slaves, as well as armed Jesuits and Friars.

The Dutch were demoralised to see their commander, Captain Ruffijn, felled by a shot. Terrified by the furious onslaught of the defenders, particularly their African slaves who were merciless and gave no quarter, they turned and bolted, flinging away their arms and standards. Their rearguard also panicked and the sailors, worried that the longboats would be capsized by their fear-crazed comrades, put to sea, leaving the troops to the cold steel of the Portuguese and their Africans or to a watery grave.

It has been estimated that the Dutch suffered some five hundred casualties, including eighteen officers killed. One captain and several soldiers were made prisoners. They lost all their cannon, flags, drums and other equipment. The victors collected over 1000 weapons from the battlefield. The defenders suffered the loss of four Portuguese, two Spaniards and several African slaves. Some twenty were wounded.

It has been estimated that the Dutch suffered some five hundred casualties, including eighteen officers killed. One captain and several soldiers were made prisoners. They lost all their cannon, flags, drums and other equipment. The victors collected over 1000 weapons from the battlefield. The defenders suffered the loss of four Portuguese, two Spaniards and several African slaves. Some twenty were wounded.

St John the Baptist

Click to see full image

In a little over three hours on this fateful day, the mighty Dutch force was totally routed by a small but determined band of Portuguese. On the very battlefield, the victors freed their African slaves, in recognition of their loyalty and bravery.

The entire population attended a Te Deum at the Cathedral, in thanksgiving for this great victory, which was attributed to the intervention of St John the Baptist, whose feast day it was. He was declared the Patron Saint of Macau. To this day, the 24th June, Dia de São João, is celebrated in Macau with a special Mass at Sé Cathedral attended by local dignitaries.

Legend claims that the rout of the Dutch invaders was due to the apparition of St John the Baptist to the astonished Dutchmen, with a mantle into which the enemy shots were deviated.

Macaenses all over the world have traditionally celebrated this day at their homes, usually with an abundant feast which generally included rich Macaense desserts and a great, variety of exotic tropical fruits. Folklore has it that no one suffers from the aftermath of over-indulgence on this particular day, because of the protection of St John.

It is hoped that perhaps we Macaenses will revive this great custom and get together wherever we are to commemorate our patron Saint's feast day and to celebrate once again our heroic victory of 1622!

1 This is an edited version of an article first published in the Bulletin of Casa de Macau (Australia).

2 Charles R. Boxer states that 20 Japanese "had come with a fleet of Don Juan da Silva from Manila in 1621 with the object of assisting the Portuguese in Macau against the Dutch; this expedition had touched at Siam where they were overpowered and destroyed in a quarrel with the Siamese; these Japanese had escaped and now asked leave to transfer to the Dutch Service". Some 12 or 13 of these were killed in the subsequent battle in Macau. [CR Boxer, Estudos Para A História De Macau -- Seculos XVI à XVII, Fundação Oriente (Lisboa) 1991]

_wiki_public_domain.jpg)